This would be the only national park telling the story of a Jewish American

An effort is underway to honor the Rosenwald schools, created by a son of German Jews to serve rural Black communities

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A coalition of Blacks, Jews and others are lobbying for a new national park to honor the Rosenwald schools, which were founded by a son of German Jewish immigrants to serve rural Black communities in the Jim Crow era.

Julius Rosenwald made a fortune investing in the Chicago-based Sears, Roebuck and Co. He ultimately bought out the company’s founders and turned the famed catalog business into a retail behemoth not unlike today’s Amazon.

Rosenwald was inspired to create the schools after reading Booker T. Washington’s 1901 autobiography, “Up from Slavery,” and meeting with him. The schools are viewed as one of the most ambitious examples of Black-Jewish cooperation in U.S. history.

More than 5,000 Rosenwald schools were built in rural areas in 15 Southern and border states between 1912 and 1932. The schools’ many distinguished alumni include the late civil rights activist U.S. Rep. John Lewis and poet-novelist Maya Angelou.

The campaign for the Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park is led by Dorothy Canter, a retired biophysicist who worked for the federal government for 29 years. Canter is Jewish, but had never heard of Rosenwald until she saw Aviva Kempner’s 2015 documentary, “Rosenwald.”

The park proposal

A self-described “National Parks junkie,” Canter realized that “not one of the more than 400 parks told the story of a Jewish American. Not one gave an historical perspective into the Jewish values Rosenwald embodied that brought hope and change to so many African American communities and lives.”

In 2018, Canter and other like-minded activists gathered to establish the Rosenwald Park Campaign. They courted a diverse group of religious and civic groups — many predominantly Black or Jewish — to support the project. Congress in 2020 authorized a study, which is underway.

It’s not easy to establish a new national park — only Congress can bestow the designation and the National Park Service’s criteria are exacting. But the Rosenwald campaign appears to be on the fast track. It has the support of the park system’s National Register for Historic Preservation, and a month-long period for public comment ended in July.

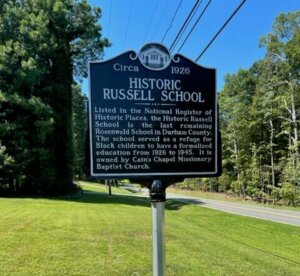

As envisioned by its backers, the park would include a visitors center in Chicago and five representative schools around the country. Ten of the 500 Rosenwald schools still standing are under consideration as park sites, including the Russell Rosenwald School outside Durham, North Carolina.

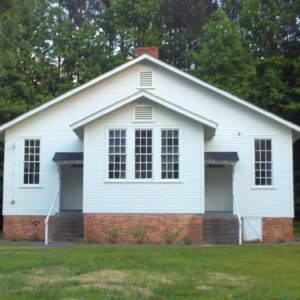

The Russell School

The Russell School is the last Rosenwald school in Durham County out of an original 17. The school closed in 1945 but was preserved by the Cain Creek Missionary Baptist Church next door, which used it as a social hall for years. Today, at least as many Russell School alumni are buried in the cemetery between the church and school as are still alive.

“This is my legacy,” said Phyllis Mack Horton, director of the nonprofit Friends of Russell Rosenwald School, her pride palpable as she pointed out the flooring, chalkboard and lone student’s desk on an informal tour. The two-room, century-old wooden structure is illuminated by natural light from floor-to-ceiling windows, a hallmark of the Rosenwald design, though electric lights were later added.

Rosenwald and Washington met in 1911. Washington wanted to build small schools in African American communities across the South, each staffed with two to four teachers. Initially, Rosenwald funded the schools himself. Beginning in 1917, a philanthropy he created, the Rosenwald Fund, provided between a fifth and a third of the money for each school. Another third came from local communities contributing land, labor, materials or cash. The final third came from local and state governments, which saw the project as a way to keep African Americans — a cheap local labor force — from joining the Great Migration out of the South.

The schools were state of the art, designed by a team of Black architects led by Robert R. Taylor, MIT’s first Black graduate and the first accredited African American architect. By 1928, Rosenwald schools served a third of Black children in the rural South.

Racism and antisemitism

Rosenwald’s interest in helping Black Americans was inspired not only by the era’s rampant racism but also by its antisemitism. As the son of German Jews who “fled centuries-long persecution in Europe,” the park proposal says, he “was aware not only of the recurring pogroms against Jews in Europe but also anti-Semitism in the United States. This led him to strongly identify with the plight of African Americans.”

He was also influenced by Rabbi Emil Hirsch, a founding member of the NAACP and leader of the Reform synagogue Chicago Sinai, which Rosenwald belonged to.

Rosenwald’s interest in fostering racial equality was not confined to education. The Rosenwald Fund also provided fellowships in the arts and humanities to poet Langston Hughes, singer Marian Anderson, novelist James Baldwin, folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, photographer Gordon Parks and many other distinguished African Americans. And between 1917 and 1958, the Rosenwald Fund contributed $33,500 to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which helped defend the Scottsboro Boys and later bankrolled legal challenges to segregation, including Brown v. Board of Education.

The national park proposal comes during a renaissance in civil rights activity and renewed interest in African American history across the South, with recently established museums in Montgomery and Birmingham, Alabama, and Charlotte, North Carolina.

Empowering Black communities

But while the pragmatic partnership between Rosenwald and Washington has been compared to the more activist bond between Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Heschel, the Rosenwald schools ostensibly avoided politics and activism. This was partly because they received government funding.

In practice, though, the schools helped empower Black communities. When classes ended, partitions between classrooms were rolled back to create auditoriums where the Black “community could gather without prying white eyes,” said Joanne Abel, who wrote about the schools in “Persistence and Sacrifice.” There “they could discuss anything the community wanted to talk about.” Rosenwald alumni include the civil rights leaders Medgar Evers and Vernon Dahmer, both of whom were murdered for their activism.

Harry Boyte, a political philosopher and activist, would like the park proposal to include more about this aspect of the schools’ history. Specifically, he thinks the proposal should include the story of the so-called “Jeanes Teachers” who set up and ran many of the Rosenwald schools. They functioned as community organizers, Boyte writes in Library Quarterly, “working with thousands of communities across the South to build schools and libraries and many other community empowering groups and institutions.” The teachers’ corps, made up primarily of Black women, was named for Anna Jeanes, a white Quaker woman who left $1 million to fund Black education in the South.

Preservation or development?

Boyte and others would also like to see the surviving schools evolve into contemporary spaces for community development, reviving the self-help spirit of their origins, rather than focusing on historic preservation alone.

“My personal lean would be toward development of new civic spaces,” said Ernest Comer, a Georgia-based social impact consultant who focuses on African American communities. “I would prioritize that over creating spaces that only exist to display what was. Our nation is in a season where investment in existing civic spaces as well as the development of new civic spaces could really have a massive impact on the quality of relationships across cultures. Making investments in the quality of those relationships is more important than investing in spaces that only create exposure to what existed historically.”

While Rosenwald schools were of critical importance in large Black communities, they were equally important in small, isolated places like Long Ridge in Madison County, North Carolina, a four-hour drive west of Durham in the Blue Ridge Mountains. There the exquisitely restored Anderson Rosenwald School served an African American community of about 100 families.

“There was a sense of community there,” said David Lloyd Briscoe, a University of Arkansas sociology professor and Anderson School alumnus. “When I say community, I mean not only within the school but in the community supporting the school. Without a doubt there was a sense of ownership.”

He added: “The teachers knew that we were living in a society that didn’t place value on Blackness.”

Russell Mack, a graduate of Durham’s Russell Rosenwald School, recorded an interview, now on the school’s web site, reflecting on the lasting significance of the program.

“If we can bring that history out — how we started and where we come from — I think it would help motivate some folks. If you see where you come from, you know where you are going.”