Postcard from Pittsburgh, on the 4th anniversary of Tree of Life massacre

For Barry Werber, a survivor of the deadliest antisemitic attack in American history, memory is a blessing and curse

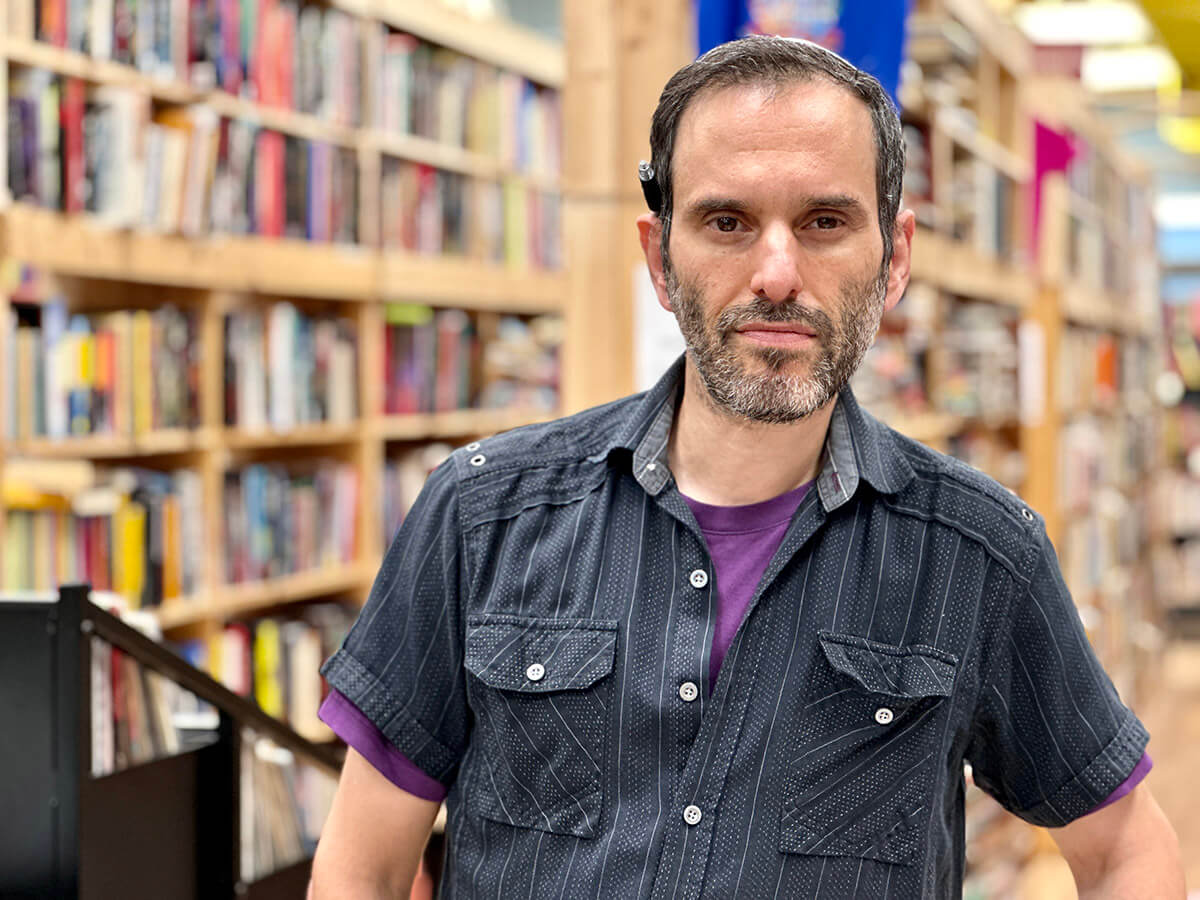

Barry Werber, a survivor of the Tree of Life massacre, on his porch at his home in Pittsburgh. Photo by Benyamin Cohen

Start talking with Barry Werber about his long-haired dachshund, Mitsie, and you should make yourself comfortable. It’ll be a while. He’ll show you the oil painting of Mitsie and the dog-faced bowl as you walk into his humble home near the Squirrel Hill neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

He’ll regale you with tales of the annual Weiner 100 Dachshund Race at a local amusement park. Hanging in the dining room is a certificate for a “Howl-O-Ween” costume contest that Mitsie entered — way back in 2007. What you won’t see in the house is the actual Mitsie. She died, at 17, five years ago.

Werber, 80, is a man who relishes a good memory. It might start with Mitsie, but stick around and he’ll likely share his love of D.C. superheroes — “I can’t wait to see ‘Black Adam’” — or that time his dad took him to Forbes Field to watch a wrestling match between Mr. Clean and Gorilla Monsoon.

But remembering the past is both a blessing and a curse. Because alongside Mitsie and Mr. Clean there is the memory of that awful day exactly four years ago — Oct. 27, 2018 — when Werber was at the Tree of Life synagogue for Shabbat services and a man burst in blasting bullets, eventually murdering 11 people in the deadliest antisemitic attack in American history.

Werber was in the basement with his fellow congregants when they heard the noise. He escaped into a storage room with two others, Carol Black and Melvin Wax. “We couldn’t find the light switch,” he recalled in a two-hour interview on Wednesday, the day before the anniversary. “It was pitch black.”

After a few moments, Wax, who was hard of hearing, thought the shooting had ended, so he took a fateful step outside the storage room and was instantly shot dead. His body fell back into the storage room, and the shooter, Robert Gregory Bowers, stepped inside. Through the darkness, Werber said, Bowers could not see Black hiding behind the door or himself toward the back of the room.

“To this day, I can’t go into a room and sit with my back facing the door,” he told me, sitting at the head of his dining table, staring at his front door.

In the years since, Werber has gone to plenty of therapy. Six months after the shooting, he ventured back into the building, down into the basement and into that storage room. “I had my psychiatrist on one side and my wife on the other.”

Black and gold forever

Driving into Pittsburgh, as I did on Wednesday, can be a dramatic experience. You come through the Fort Pitt Tunnel and out onto a bridge that overlooks the intersection of three rivers on one side and the gleaming skyscrapers of downtown on the other.

Pittsburghers are well known for their hometown pride. Once the industrial engine known as Steel City, it is now Steelers City. Everyone roots for the football team, even now, in a season when they’ve won only two of seven games; the team’s trademark black and gold are in shop windows, on bumper stickers and woven enough into Werber’s home to think he might work for the franchise.

He was wearing a Steelers sweatshirt and showed me his collection of Steelers hats — so many hang at the entrance to his bedroom you cannot see the door.

These days, the innovation at local universities has spawned a new tech economy, with Google, Microsoft, Uber, Facebook, Amazon and Apple all having opened offices here over the last decade. There’s a newly vibrant urban life of hipster cafes and walkable neighborhoods — including here in Squirrel Hill, home of Mister Rogers — and Tree of Life.

Along the bustling sidewalks of Murray and Forbes avenues, when I told people I was visiting for “the anniversary,” I didn’t have to explain any further.

Outside the kosher butcher shop, I met Dea Fern, 62, who was a member of Tree of Life, and said it makes her sad that when people think of Pittsburgh’s Jewish community now, they think of tragedy. “I want them to know it’s warm, it’s vibrant, it’s celebratory,” she said. “It’s like a mini-Jewish paradise.”

Down the block, I bumped into Rabbi Yitzi Goldwasser, the director of a local Chabad, who noted that the neighborhood has synagogues of all denominations. “The unity that was already here became much more” after the shooting, he said. “The Lubavitcher rebbe used to say that labels are for clothing, not for people.”

Mark Oppenheimer, who wrote a book about how Squirrel Hill recovered after the Tree of Life massacre, said the neighborhood was a testament to the power of people “being in each other’s lives.”

“When the worst stuff goes down,” he explained, “how extremely important it is to be amongst other Jews who care and make your suffering their problem as well.”

Amazing Books and Records is on Forbes Avenue, between a European wax center and a ramen bar, and across the street from a kosher Dunkin’ Donuts. The bookstore owner, Eric Ackland, had a pen behind his ear and a pencil in his hand as he shared a story of the serious car accident he and his wife were in a few months before the Tree of Life attack.

“We had six weeks worth of home-cooked meals from volunteers,” Ackland said, plus $30,000 in donations. “I’d already seen then what an amazing thing it is to be a member of this community.”

‘10.27’ is their 9/11

A few blocks from the bookstore is the JCC, and on the third floor is the office of the 10.27 Healing Partnership, which hosts monthly meetings with survivors of the attack, organizes commemorative events around town and offers educational resources and post-traumatic support.

The group’s director is Maggie Feinstein, a native Pittsburgher, who was busy Wednesday planning for events tied to the English anniversary and, in a few weeks, on the Hebrew calendar’s yahrzeit. “How do you commemorate a mass violence incident that is uniquely Jewish?” she asked. Torah study groups in memory of the deceased and tikkun olam events throughout the city, she answered.

The 10.27 group – Jews here say the numbers like New Yorkers do 9/11 – is also working with the survivors and families of the dead to build a memorial slated to soon begin construction.

Daniel Libeskind, the star architect who built the Jewish Museum of Berlin, is reimagining the Tree of Life site. The child of Holocaust survivors, he was also the master planner behind the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan.

The new 45,000-square-foot complex will include event spaces, a sanctuary, museum, memorial and an incubator for ideas to combat antisemitism. The historic limestone façade of the original sanctuary will remain as a defiant symbol. Four Pittsburgh nonprofits have each donated $1 million to help fund the construction.

Feinstein told me she does not expect her group to be around forever. Its federal grants will soon run out, and while she expects other donors to keep it going for a few more years, she thinks longstanding Jewish organizations will eventually absorb different parts of 10.27’s mission. “It’s ephemeral,” she said. “I have faith in that.”

‘It’s deepened my faith in my faith’

Werber, long an active member of the synagogue choir, now mostly attends services on Zoom. Not out of fear or post-traumatic stress, but because his wife, Brenda, has lung cancer and is not mobile enough to go. “You don’t feel the camaraderie, you don’t feel the closeness,” he acknowledged. “You don’t see anybody from the waist down.”

Brenda, who is 81, was sitting on the couch, watching a segment about the anniversary on the local news. Werber does not suffer from survivor’s guilt. “I feel sorry for those who lost loved ones, but I’ve always professed from day one that someone had to be here to take care of my wife,” he said, adding: “If anything, it’s deepened my faith in my faith.”

Bowers, the shooter, is slated for trial in the spring. Werber is on the witness list. “I’m hoping I can be there, but I’m not looking forward to it,” he said. “There’s no closure for us. It’s on and on and on.”

As I got up to leave, Werber walked me back to his office, and opened a folder on his computer labeled “Photos.” Inside are pictures he’s collected of the 11 people who were killed on that October morning in 2018.

He showed me several of Richard Gottfried, a dentist who volunteered with refugees, at various synagogue events — marching outside with a Torah, reading the megillah on Purim in a funny hat.

Then Werber pulled up a photo of Melvin Wax, a retired accountant who was always ready with a joke — the 87-year-old man who was shot dead in front of him.

“I just feel blessed that I was able to leave that building when so many other people didn’t,” he said. “We didn’t choose this, but now we have to speak out.”