What do you do when neo-Nazis start projecting swastikas across your city?

Two white supremacist groups picked Jacksonville to launch a campaign projecting antisemitic messages on landmarks. Local Jews wondered why their city had been picked, and how to respond.

Several Jewish community leaders in Jacksonville praised the city as a wonderful place to live, even as they acknowledged various antisemitic incidents. Photo by Getty Images

When thousands of college football fans flocked to Jacksonville for an annual rivalry game between Florida and Georgia on Halloween weekend, they saw an unprecedented series of antisemitic displays. That Friday, a group of men stood on a freeway overpass with painted banners. “Honk if you know it’s the Jews,” one read.

That same night, an identical message appeared scrolling across a Wells Fargo skyscraper and the Lynch Building, a historic apartment tower, both downtown.

White supremacists had unfurled banners like that before, but what came next was new. As the sold out crowd at TIAA Bank Field started to stream out of the stadium on Saturday, they were greeted by a message more than 10 feet high and roughly the length of a billboard, projected with lasers onto the back of the structure. “Kanye is right about the Jews,” read the flickering, handwritten script.

“Kanye is right about the Jews” was projected across the TIAA Bank Field amid Georgia-Florida game day celebrations in Jacksonville, Floridahttps://t.co/fphTIIXlwEpic.twitter.com/TS9Ve0sVax

— philip lewis (@Phil_Lewis_) October 30, 2022

Jacksonville quickly became the epicenter of antisemitic projections on buildings. “Tom Brady got Jew’d” appeared on a parking garage the following month. In December, projections showed up on a downtown bridge and on a former navy ship docked in the St. Johns River. A towering symbol that combined a swastika and cross was projected in January onto the headquarters of the railroad company CSX, one of Jacksonville’s largest employers.

While the most dramatic incidents made national headlines, the Anti-Defamation League tracked more that escaped coverage. It found at least seven such events in and around Jacksonville — and three more elsewhere in Florida — starting on Oct. 29 and running through January, when the city council outlawed them, according to data shared with the Forward. But the laser projections have since spread throughout Florida. In recent weeks, officials from Palm Beach to Daytona, where spectators at the International Speedway in late February were greeted with an antisemitic projection, have discussed how to stop the offensive displays.

It’s a new tactic spearheaded by the Goyim Defense League, the white supremacist group that has spent the last few years demonstrating on overpasses and encouraging followers to plaster neighborhoods across the country with antisemitic flyers. The group’s leader, John Minadeo, moved from California to Florida last fall. The projections also seemed to earn GDL and NatSoc Florida, a local neo-Nazi group that partnered with Minadeo, more publicity than previous stunts.

The stadium incident was covered on national television. Other images of the projections received media attention and circulated widely on social media as shocking examples of public antisemitism. The projection phenomenon has even spread to Europe, where an offensive message appeared on the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam in February.

“They’re controlling the narrative,” said Mariam Feist, chief of the Jewish Federation and Foundation of Northeast Florida.

Local Jews were alarmed by the projections in Jacksonville, while city leaders worried about the city’s reputation. “I wasn’t on CNN because they were talking about how wonderful Jacksonville is — and it is angering the business community, it is angering the civic leadership,” Feist added.

The last thing local leaders wanted was to become known as a city that was friendly to Nazis, and they rallied to rehabilitate Jacksonville’s reputation and put an end to the graphic displays. The city council made it illegal to project images on a building without the owner’s permission in late January, which has stopped the local activity for now, and the federation is doling out grants to improve tolerance in the community. But the stunts left a gnawing question for Jacksonville’s tight-knit Jewish community: Was it just bad luck that white supremacists had picked their city as proving ground for their new technology, or evidence of a deep antisemitic vein in the region?

David Miller, a major civic booster, said he doesn’t think the city is a particularly antisemitic place. “It’s no more in Jacksonville than it is anywhere else,” said Miller. On the other hand, he acknowledged, “They chose Jacksonville as the ripest place to organize and begin their campaign of hate.”

Jacksonville’s Jews have been left wondering how to best respond to antisemitism in their midst.

‘I don’t get nervous everyday’

Fast-growing Jacksonville, which proudly calls itself the “Bold New City of the South,” sits in the northeast corner of a state with a high concentration of antisemitic groups.

An ADL report released last fall found that “Florida is home to an extensive, interconnected network of white supremacists,” including the Goyim Defense League and NatSoc Florida. The state ranked third among all states in the number of antisemitic incidents perpetrated by white supremacists since 2002, according to an analysis of ADL data by the Forward. The ADL counted 182 of those events in Florida, about 9% of all incidents in the country.

But the antisemitic projections seem to have had a limited impact on the daily lives of Jacksonville’s Jewish population, which various estimates place between 10,000 and 15,000. Feist, the federation chief, emphasized that the Jews of Jacksonville don’t feel besieged by the local white supremacist activity.

“It’s a great place to live,” she said. “I don’t get nervous everyday when I leave my house and get into my car.”

Rabbi Maya Glasser, who leads Congregation Ahavath Chesed, the local Reform synagogue, said that after the first incident last October, some families had expressed concerns about whether it was safe to send their children to Hebrew school.

The answer, Glasser said, was yes. Security officials had reassured Jewish leaders in the region that there was no imminent threat.

“The advice is that people can project things all they want, but they didn’t see a threat in terms of crossing a line and causing physical harm to Jewish institutions,” she said.

Ben Popp, a researcher at the ADL Center on Extremism who authored the report on Florida, said the total number of white supremacists who participate in antisemitic demonstrations is relatively small. The hate groups often join forces to boost turnout for events, and even then 20 people is considered “a really big event,” Popp said in an interview.

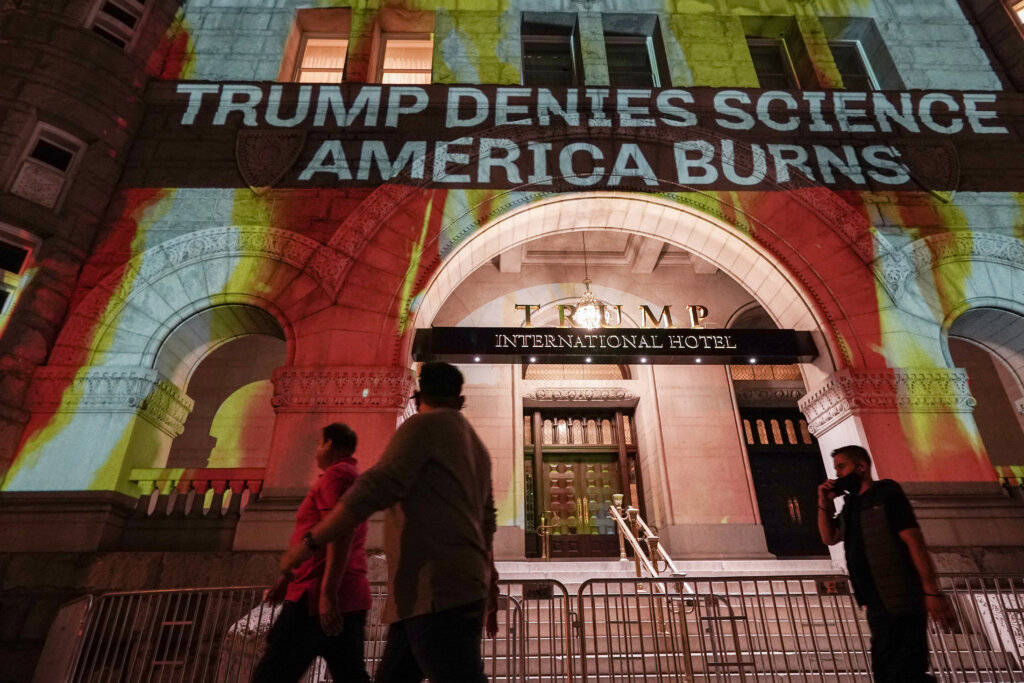

The strategy of projecting messages onto buildings with lasers was popularized by progressive activists during the Trump administration, who cast slogans and images onto the president’s hotel in Washington, D.C., among other targets. The white supremacist projections require more resources than dropping cloth banners on freeway overpasses, or tossing printed sheets of paper into front yards. Popp estimated there was an upfront cost of a couple thousand dollars in equipment, along with a bit of technical knowledge, but said it was simple enough that the tactic could easily spread to new locations.

None of the projections have been on buildings that house Jewish institutions, or reference anything specific to Jacksonville’s Jews, which Popp said he believed was an intentional decision to avoid anything that could be considered targeted harassment and expose the perpetrators to criminal charges. That makes the threat less direct than several decades ago, when Jacksonville’s Jewish community last found itself in white supremacist crossfires: In 1958, an organization calling itself the “Confederate Union” took responsibility for bombing the Jacksonville Jewish Center and declared that they would kill Jews living in the region.

More confident in their immediate safety, much of the Jewish community’s response has been focused on initiatives designed to stave off problems in the future.

Miller, who founded Brightway Insurance with his brother Michael, donated $1 million in November to create a fund for combating antisemitism and other forms of hate in Jacksonville. Local companies, including CSX, the Jacksonville Jaguars football team, and Florida Blue, a health insurance company, have made additional contributions, bringing the account’s total balance to $1.7 million.

Feist said a committee is still determining how all the money will be spent, but some of it is already going to two long-standing priorities for the federation: hiring a security director to support local Jewish institutions and creating a community relations council, which could make it easier to communicate with local officials about antisemitism. More than 80% of federations in North America have one of these councils, which serve as the political advocacy arm of the organization Jewish community, and Feist is eager to add Jacksonville to that list.

(The federation is also donating some of the new fund to OneJax, a local nonprofit that promotes diversity and tries to build relationships across religious, ethnic and cultural lines in Jacksonville.)

Feist has struggled with the question of whether the projections and a handful of previous incidents of antisemitism in the region are isolated. “There are one-offs everywhere,” she said.

But at the same time, the community hasn’t had any formal infrastructure to track or respond to antisemitism, leaving local Jews with little more than personal anecdotes.

“They didn’t have a community security department to email or call, they didn’t have a JCRC to email or call,” she said. “A rabbi might hear it here, a neighbor hears it there, but we don’t have the real documentation.”

What the rabbi hears

The Sunshine State has seen its Jewish population grow in recent years, and while many new arrivals settle in South Florida, Jacksonville has been named an “emerging community” by the Orthodox Union. The Tikvah Fund, a conservative Jewish think tank, invited Ron DeSantis, the state’s governor and a Jacksonville native, to discuss the “vibrancy of Jewish life in Florida” at its annual conference last year.

Still, especially in northeast Florida, things are different than in parts of the country with larger Jewish populations. Glasser, the Reform rabbi, moved to Jacksonville from the New York area two years ago and said she was warned to brace for an onslaught of antisemitism.

“When I moved here, I had people say, ‘Don’t tell anyone you’re a rabbi, don’t put up a mezuzah,’” she recalled. But Glasser didn’t want to hide her Judaism, so she regularly mentions her role as a rabbi and has never encountered hostile reactions — just curiosity, and sometimes ignorance.

“Having conversations about Judaism is really different here,” she said. “More education needs to be done in Jacksonville than in New York and New Jersey.”

That has created a tight-knit Jewish community, Glasser said, and the handful of local rabbis — Jacksonville has four synagogues and two Chabads — help do this education, including through interfaith work. But much of the burden for teaching Jacksonvillians about Judaism falls on kids.

Feist said she fields complaints about antisemitic bullying in the city’s schools. In an especially egregious incident in 2019, someone sent a Jewish student “provocative pictures” of two female students whose bodies were covered in swastikas and antisemitic slurs, according to local media reports.

Alyce Bessman, a Jewish senior at Creekside High School in Jacksonville, said the swastika scandal was the first time she noticed antisemitism in the city. The following year, a swastika was painted on the door to her school auditorium. In another incident, she recalled being taunted by a group of students after they noticed someone in the group she was with wearing a Star of David necklace.

Bessman said that to her Jacksonville feels split between people who are interested in other cultures and beliefs, and those who aren’t. Many students will ask her genuine questions about Judaism, and she invites friends over for a Hanukkah party every year. But she also hears jokes about the Holocaust and people making light of antisemitism.

“Some people I’ve encountered are just very set in their ways and just don’t want to interact at all, and that can lead to antisemitism out of just pure ignorance,” she said.

Adults in the community acknowledge these issues, but also note that it’s better than it used to be. Miller, the businessman and philanthropist, loves Jacksonville. He built his company in the city, lives down the street from his brother and was sad to see it maligned on national television over the swastika projections.

“Those of us who grew up in Jacksonville know it as a very loving and supportive community,” he said.

Still, Miller can recall going to concerts as a teenager where Christians would try to convert him and tell him he was going to hell. There was also a local country club that refused to admit Jews, and cotillions and debutante balls — staples of Southern high society — to which the Jewish kids were never invited. And he can never forget the girl in eighth grade who yelled that he was a “dirty, terrible Jew” in the middle of school.

“Literally screaming,” he said. “I was just like, ‘Oh my god,’ you know? It was an out-of-body experience.”

Those more explicit forms of antisemitism have largely fallen by the wayside.

“Jacksonville’s come a long way,” said Susan Datz Edelman, an active member of Congregation Ahavath Chesed, who grew up nearby and has spent most of her life in the city. “But there’s part of it that’s very provincial.”

Edelman, 67, said the recent antisemitic projections on downtown buildings felt more sinister than the occasional offensive comment by someone who didn’t know better. The stunts have unsettled her because the threat is so unclear. The projections have literally magnified a vicious kind of hate toward Jews, but Edelman said she’s not sure if it’s just a couple loners who are responsible or an organized group that poses a deeper threat to the community.

“You can’t react proportionally,” she said. “What is it that’s out there?”