Israeli Holocaust Survivors Split Over Iran’s Acknowledgement of Nazi Crimes

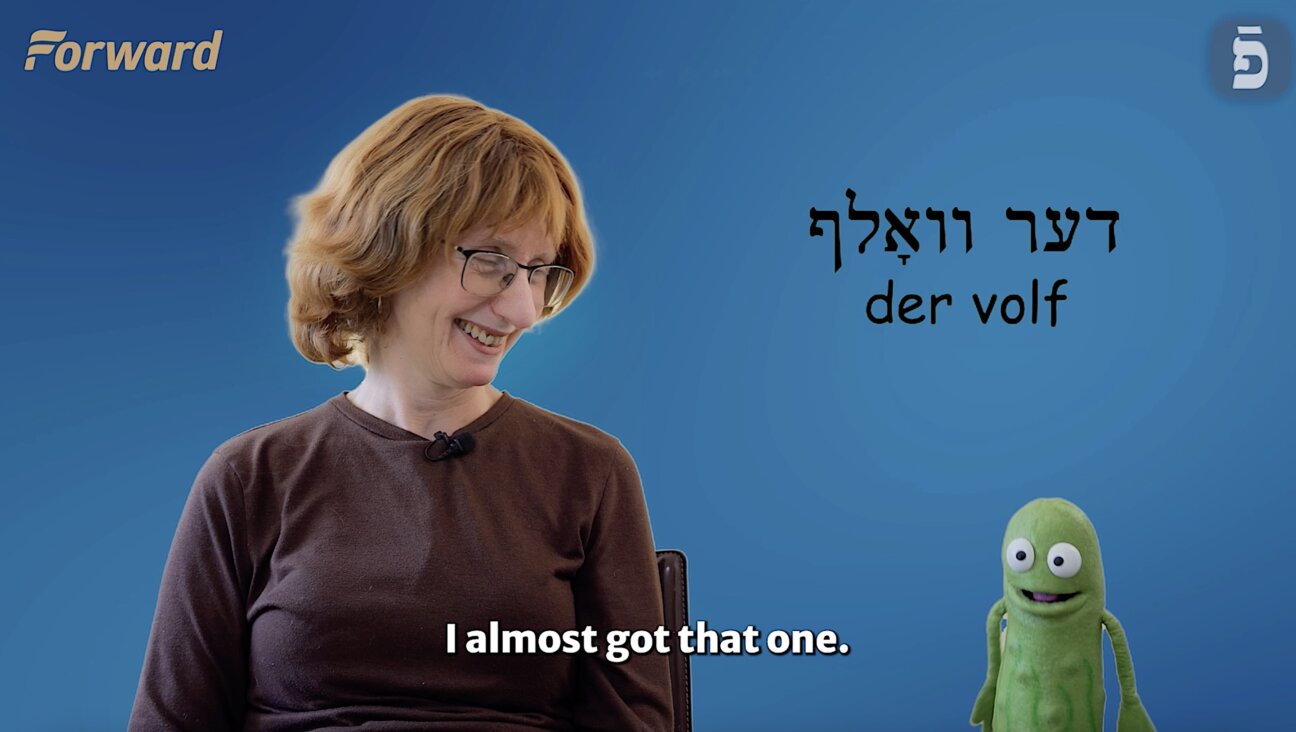

Chava Hershkovitz, winner of last year?s Miss Holocaust Survivor pageant, sees reason for hope. Image by nathan jeffay

Israel has brusquely dismissed Iran’s moves away from the Holocaust denial of its previous president. But actual Holocaust survivors in Israel are divided on how to react to the development.

“Personally, for me, it was important — it made me feel something,” said Chava Hershkovitz, 80, at the Yad Ezer L’Haver home for survivors in Haifa.

Hershkovitz, winner of last year’s Miss Holocaust Survivor pageant, was one of several survivors interviewed who saw some reason for hope in the recent statements of Iranian leaders. ““I think the population in Iran will understand Israelis and Jews better.” It could acquire a sense of “why we’re so scared,” she added, and soften towards Israel.

In contrast, Jerusalemite Chaim Maltz said that he doesn’t need anyone to validate his experiences. “As far as I’m concerned it’s irrelevant to me — I know what happened.”

Maltz, 77, thought that Iran was using Holocaust recognition to ingratiate itself with the West while continuing its anti-Western and anti-Israel agenda. “I think they want a caliphate, to knock out our state, and this may be a way towards this,” he said. “I don’t really care what they say because they are our enemies.”

The diverse reactions underlined the diverse nature of Israeli Holocaust survivors themselves. Often caricatured as a monolithic group, the survivors’ responses to the Iranian leaders’ recent remarks on the Holocaust is no less complex than those of Israelis in general, albeit with the extra twist of personal experience.

Though the issue of Iran’s nuclear program remains front and center as the core of Israel’s concerns about Iran, Israelis have been decrying the Islamic Republic’s position on the Shoah for many years. Iran’s former president, Mahmoud Ahamdinejad, frequently voiced his doubts in public about the historical reality of the Holocaust.

And for Israel, the issue acquired so much significance that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu cited it as part of the reason he ordered the country’s United Nations representatives to boycott the September 24 speech by Ahmadinejad’s recently elected successor, President Hassan Rouhani, to the world body’s General Assembly.

But shortly after Rouhani delivered his UN speech he acknowledged and condemned crimes committed by the Nazis towards Jews and non-Jews, speaking through an interpreter on CNN. But he added, “when it comes to speaking of the dimensions of the Holocaust, it is the historians that should reflect on it,”

The condemnation was short of a comprehensive acknowledgment that the Holocaust took place on the scale understood by Western historians. Furthermore, a presidential advisor was quoted by a news agency loyal to the regime claiming that Rouhani had been mistranslated and had never even used the term “Holocaust. “

But five days later, his foreign minister clearly was talking about the Shoah. Mohammad Javad Zarif, who accompanied Rowhani to the United States, told ABC News bluntly that “the Holocaust is not a myth.” He went on to comment that the Holocaust “was a heinous crime, it was a genocide, it must never be allowed to be repeated.”

Jack Fogel, an 89-year-old survivor who lives in Jerusalem, related to the Iranian statements on a personal level, seeing the winning over of every Holocaust denier as a vindication of his own hardship. “I’m glad that they are now acknowledging that [the Holocaust] existed,” he said. “It’s a move in the right direction.”

But Moshe Stenger, who lives in the same Haifa home as Hershkovitz, dismissed the Iranians as “just making a show” for the West. He thought they would continue to deny the Holocaust domestically. “They say what suits them — it’s not real,” said Stenger, 76. He added: “I don’t pay attention to what the Iranians say. Every minute it’s something different.”

Rabbi David Weiss Halivni, a noted Talmudist who spent time in several camps during the Holocaust and went on to have a prolific academic and clerical career in America before moving to Jerusalem, took a similar view. “It makes no difference to me. It’s all politics and when the opportunity arises [Iran’s leaders will] change,” he commented.

Some public opinion experts believe the extraordinary interest in Iran’s position on the Holocaust is not just because partly a result of Netanyahu’s framing of Iran and the Holocaust as twin existential issues. Meir Eran, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv commented: “We are very touchy and emotional about the issue of our existence and the Holocaust is an existential issue for us, and the leadership has managed to sway the public — unfortunately — that Iran is an existential issue.”