When almost nobody else would, Hank Greenberg backed a Black player fighting for free agency

Fifty years ago, the Jewish Hall of Famer testified on behalf of Curt Flood, whose stand against MLB’s reserve clause made him a key figure in athletic activism

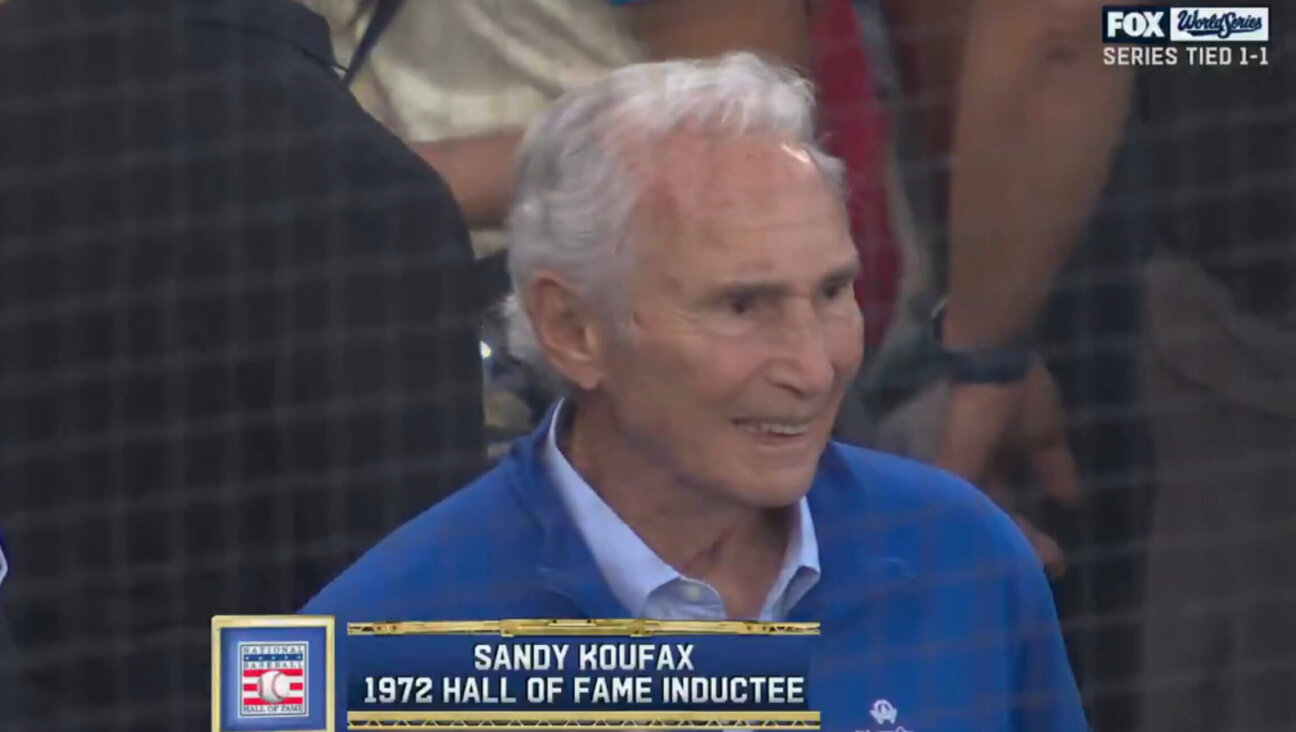

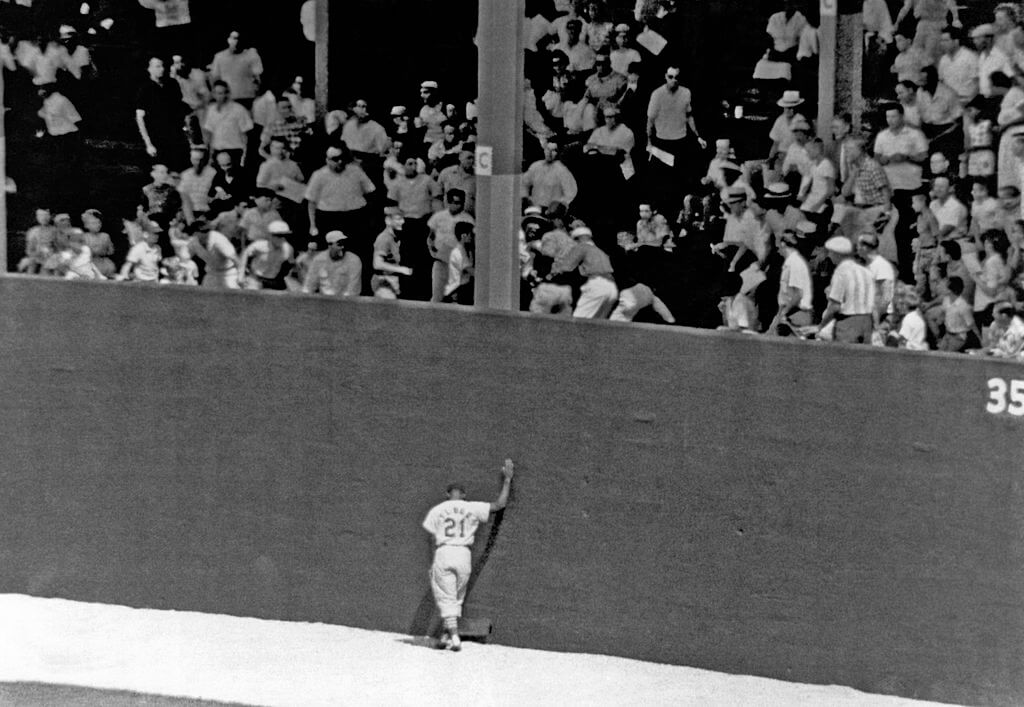

St Louis Cardinal outfielder, Curt Flood, leans against the wall as he symbolizes the frustration of the Cardinals as the fans scramble to get a Phillies home run ball, St. Louis, Aug. 12, 1962. Photo by Underwood Archives/Getty Images

When a Black outfielder fought for his economic freedom against baseball owners a half-century ago, Hank Greenberg, the Jewish Hall of Famer, was one of a handful of former players who sided with him — even though he had been a baseball executive after he retired.

In 1970, Curt Flood challenged Major League Baseball’s reserve clause, which bound players to their teams until released or traded. His lonely crusade made Flood a pariah in the sport, and led to death threats. The Supreme Court ruled against him 50 years ago last month, but Flood’s case helped lead to free agency a few years later.

When Flood’s antitrust case started out in a federal courtroom in New York in 1970, no current player testified on his behalf, fearful of retribution.

But Greenberg, known as the “Hebrew Hammer” playing mostly for the Detroit Tigers in the 1930s and ’40s, backed Flood at the trial. So did Jackie Robinson, who had broken baseball’s color barrier in 1947, and Jim Brosnan, who rocked the baseball boat by writing a candid, behind-the-scenes book about the life of baseball players.

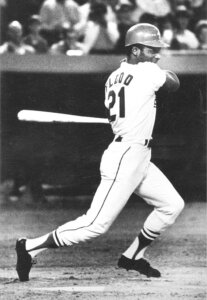

Flood had been a star outfielder with the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1960s. After the team traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1969, Flood wrote a letter to baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, asking that he be declared a free agent instead.

“After 12 years in the Major Leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes,” Flood wrote. “I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.”

He sat out the 1970 season and pursued his case against MLB. At Flood’s trial that May, Greenberg testified that “the reserve clause is obsolete, antiquated and definitely needs change.” His appearance against baseball owners was striking because he had been a part owner and general manager of two MLB teams himself after his playing days were over. His fellow investor with those teams, Bill Veeck, who had been the first owner to sign a Black player in the American League, also testified on Flood’s side.

“We need more harmonious relations between players and owners, and we need to repair baseball’s image with the public,” Greenberg said. “The reserve clause has been in the news since 1923, and has brought objections from players, and confused the public. We must recognize that times have changed and must go forward harmoniously and the first step, the last step, is to abolish the existing reserve clause and work out a substitute.”

Under cross-examination, he discussed the issue as a prospective owner: “I’d be happy to invest in a club tomorrow if there were no reserve clause. The owners should have some control over players, but it should be limited,” and suggested a five-year contract would be fair to both sides — close to the six years that teams currently have control of players before they can seek free agency.

Robinson, who was active in the civil rights movement, called the reserve clause one‐sided in favor of the owners, and argued that it “should be modified to give the player some control over his destiny. Whenever there is a one-sided situation, you have a serious, serious problem. If the reserve clause is not modified I think you will have a serious strike by the players.”

A drawn-out legal battle

A few months after Flood’s trial, Judge Irving Ben Cooper ruled against him in his antitrust challenge, which wasn’t a surprise, since the Supreme Court had granted baseball an exemption from antitrust laws in 1922.

“Judge Cooper only held that it is up to the Supreme Court to overrule the Supreme Court,” said the baseball union’s executive director, Marvin Miller, adding that his side would appeal. “I think everyone knew that it would be very difficult for a district court to overrule the Supreme Court.”

(Cooper, Miller, and an attorney for Flood, former Supreme Court justice Arthur Goldberg, were all Jewish.)

The ruling was upheld by a federal appeals court in April 1971 — the same month that Flood quit the sport after an abortive comeback effort with the Washington Senators, when he hit just .200 in 13 games. So even though his career was over, his lawsuit was heading to the main stage: the Supreme Court.

Goldberg, who had stepped down from the court in 1965 at President Lyndon B. Johnson’s urging to serve as the U.S. representative to the United Nations, represented Flood at oral arguments in March 1972. But he didn’t have a good day. In his book, “A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood’s Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports,” Brad Snyder wrote that Goldberg gave a “feeble factual recitation” of Flood’s career, and that Goldberg’s friend, Justice William Brennan, cringed during his presentation. Goldberg betrayed his lack of baseball knowledge by referring to the several “Golden Gloves competitions” Flood had won.

In June 1972, the Supreme Court ruled 5-3 against Flood, upholding baseball’s quirky antitrust exemption. Writing for the majority, Justice Harry Blackmun — who occupied Goldberg’s old seat — said that although the original 1922 ruling was an aberration, “it is an aberration that has been with us now for half a century, one heretofore deemed fully entitled to the benefit of stare decisis, and one that has survived the Court’s expanding concept of interstate commerce.” (Stare decisis is a legal principle that means to let the decision stand.)

Flood’s career and case were both over, but not the cause. Having shined a light on an archaic practice, his challenge helped build momentum for its elimination, and in 1975, an arbitrator struck down the reserve clause. Free agency soon followed.

“I doubt Curt or anyone — on or off the field in any sport — could fully contemplate the significance of the stance he took back in 1969,” MLB Players Association executive director Tony Clark said in 2019, on the 50th anniversary of Flood’s letter to Kuhn, “but as a child and student of the civil rights movement, Curt had a heightened sense of awareness about justice and fairness.”

Years after Flood’s crusade, Congress recognized his contribution to the sport when it passed the Curt Flood Act of 1998, which chiseled away at the sport’s antitrust exemption by making actions affecting major league baseball players’ employment subject to antitrust laws.

Flood, who died in 1997 at the age of 59, is recognized today as one of the key figures in athlete activism. As USA Today baseball columnist Bob Nightengale wrote recently:

“There is Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947. There is Larry Doby, who did the same in the American League a few months later. And there is Curt Flood, whose act of bravery will never be forgotten, and an integral chapter in the Civil Rights era.”

Bond between Greenberg and Robinson

It was fitting that Robinson and Greenberg joined forces on behalf of another lonely player. Their careers overlapped by just one year — when Greenberg was capping his playing career as a 36-year-old first baseman for the Pittsburgh Pirates, and Robinson was a rookie with the Brooklyn Dodgers. But Greenberg, who faced antisemitism from players and fans during his career, quickly won over Robinson.

The two men collided at first base during a series in May, one month into Robinson’s trying first season. Robinson encountered countless incidents like this by malevolent opponents, but when he reached first base the next time, Greenberg told him: “I forgot to ask if you were hurt in that play.”

Robinson said he was OK.

“Stick in there,” Greenberg told him. “You’re doing fine. Keep your chin up.”

“Class tells,” Robinson said after the game. “It sticks out all over Mr. Greenberg.”

“Jackie Robinson, first Negro player in the major leagues, has picked a diamond hero — Hank Greenberg — rival first baseman of the Pittsburgh Pirates,” The Associated Press reported at the time.

In his autobiography, Greenberg recalled that during that series in Pittsburgh, his Southern teammates yelled at Robinson, “Hey coal mine, hey coal mine, hey you black coal mine, we’re going to get you! You ain’t gonna play no baseball!”

Greenberg wrote that he couldn’t help admire Robinson as he ignored the taunts:

“Jackie turned his head. He was like a prince. He kept his chin up and kept playing as hard as he could. He was something to admire that afternoon.”

“I identified with Jackie Robinson,” he added. “I had feelings for him because they had treated me the same way. Not as bad, but they made remarks about me being a sheenie and a Jew all the time.”

Four months after the court turned away Flood’s challenge, Robinson died at the age of 53. Greenberg attended the funeral at the Riverside Church in New York, along with Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley and many current and former players.

“Tears clouded the saddened eyes of Peter O’Malley, an Irishman; Hank Greenberg, a Jew; and Pee Wee Reese and Ernie Banks, baseball greats with different colored skins,” the Chicago Tribune reported.