The Super Bowl is upon us. What does the Torah say about sports betting?

Plenty of Jewish people seem likely to join the action on Sunday

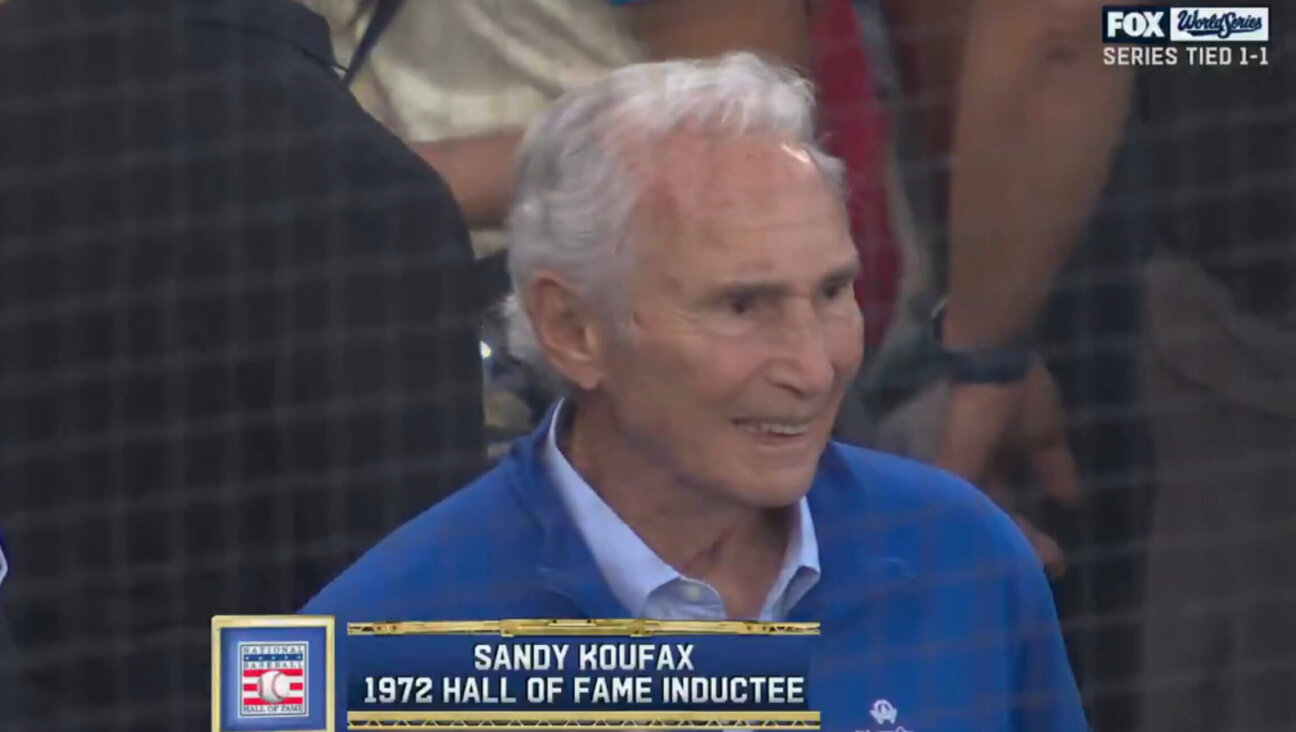

Sports betting: kosher or shanda? Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images

Betting on the Super Bowl is an American pastime on par with the Thanksgiving Day nap, if not the dinner itself. But in Jewish tradition, gambling is like shrimp: Just because it’s popular, fun and usually harmless, doesn’t mean the Torah feels good about it.

With legal online sports betting currently operational in 33 states and Washington, D.C., the Super Bowl is poised to become the most wagered-on event in U.S. history, with over $1.1 billion in bets projected by the gambling site PlayUSA — and that number doesn’t include off-book wagers like your Super Bowl party’s squares game.

But the idea may disturb modern poskim — that is, rabbinic authorities who decide on matters of Jewish law — who say that gambling in any dose is frowned upon.

Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, widely regarded as the face of 20th century Modern Orthodox Judaism, was once asked whether it was permissible to go to a casino for a single visit.

“It’s a bad habit, don’t do it!” Soloveitchik is quoted replying in Gray Matter, a book about contemporary Jewish issues that contains a chapter on gambling. Soloveitchik’s opinion is fortified by pretty much every other authority on halacha before and after.

It’s not just Orthodox rabbis who don’t like gambling. The Central Conference of American Rabbis, a Reform Judaism umbrella organization, passed a resolution on gambling in 1984, stating, “The Jewish tradition looks with disfavor upon organized gambling activity as non-productive and threatening to the social fabric of society.”

The source of Jewish apprehension around gambling is a single line in the Talmud that says a mesachek b’kuvya — literally, a dice player — cannot be accepted as a witness. This is generally interpreted as someone who does so professionally, not recreationally. Later authorities such as Maimonides and Rabbi Yosef Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch — the base text of contemporary Jewish law — expand the ban to even recreational settings.

But the Talmudic prohibition is not due to the risk of addiction. Discussing this passage, the Sages — living around the turn of the fourth century — offer two possible explanations for why the activity is disqualifying: because winning a bet is akin to theft, or because the profession offers no value to society.

And yet, we bet

Nevertheless, plenty of Jewish people seem likely to join the action on Sunday, judging by a flurry of responses from bettors across the spectrum of avidity to a tweet I posted earlier this week. And it’s become an annual tradition for rabbis to place charity wagers on the outcome of major sporting events.

Rabbi Avi Schwartz, an Orthodox rabbi who works with students at Rutgers University and runs a popular Jewish Twitter account, told the Forward he plans to lay about $60 on a squares game on Sunday. (In squares games, people receive a digit at random, and win when it’s the last digit of one team’s score at the end of each quarter.) He said he’s comfortable with a squares entry because he plans to donate any winnings to charity, and because it’s closer to buying a lottery ticket than to gambling.

Lotteries are OK, if not encouraged, modern Orthodox authorities generally agree, because the buyer consents fully to the sale at time of purchase and no money is directly taken from someone else as part of the deal, making the activity comparable to purchasing stock. (A caveat: Rav Ovadia Yosef, a leading Sephardic authority who died in 2013, banned lottery tickets.)

“It’s probably one of the more muttar (permissible) forms of gambling, but it’s probably not a great idea to feed into the gambling culture,” Schwartz said. “The amount of pain that this culture causes is enormous.”

Moral considerations also factored into the decision by modern Orthodox rabbis to prohibit gambling. Rabbi Mordechai Willig, one of the religious heads of Yeshiva University, banned all forms of the activity in 1996 from the Orthodox youth movement NCSY — even fantasy football leagues — calling gambling “the antithesis of wisdom.”

On that matter, the rabbis and addiction experts align.

Even small, innocent-seeming bets can be a gateway to addiction, according to Brad Ruderman, coordinator of the gambling treatment program at Beit T’Shuvah, an addiction treatment center in Los Angeles.

Decrying the “free money” sports betting websites use to entice new customers, Ruderman said most of the people he treats for gambling addiction these days started online.

“They don’t wake up in the morning, thinking I’m going to go place a $10,000 bet on the Lakers tonight,” he said. “It starts small, it starts at $100, and then it’s a progressive disease.”

That warning will go unheeded by Michael Luxemburg, a director/producer who bets on football throughout the season. Luxemberg says he plans on betting about a quarter of his season earnings — about $300 total — on the game’s outcome, the over/under on the length of the national anthem, and perhaps a few other prop bets he feels can be won more easily.

“I know that it’s ‘outlawed by Jewish standards’ or whatever,” Luxemberg, 32, said in a Twitter message, “but to me it falls in the broader category of non-modern regulation that doesn’t account for how stuff works in a contemporary setting.

“I.e., we don’t get sick from shrimp, so there’s no huge reason not to eat it in the context of the creation of those regulations.”