‘You made me the greatest’: Muhammad Ali’s beloved cornerman was Jewish

Drew Brown was known as the heavyweight champ’s personal poet, penning ‘float like a butterfly, sting like a bee’

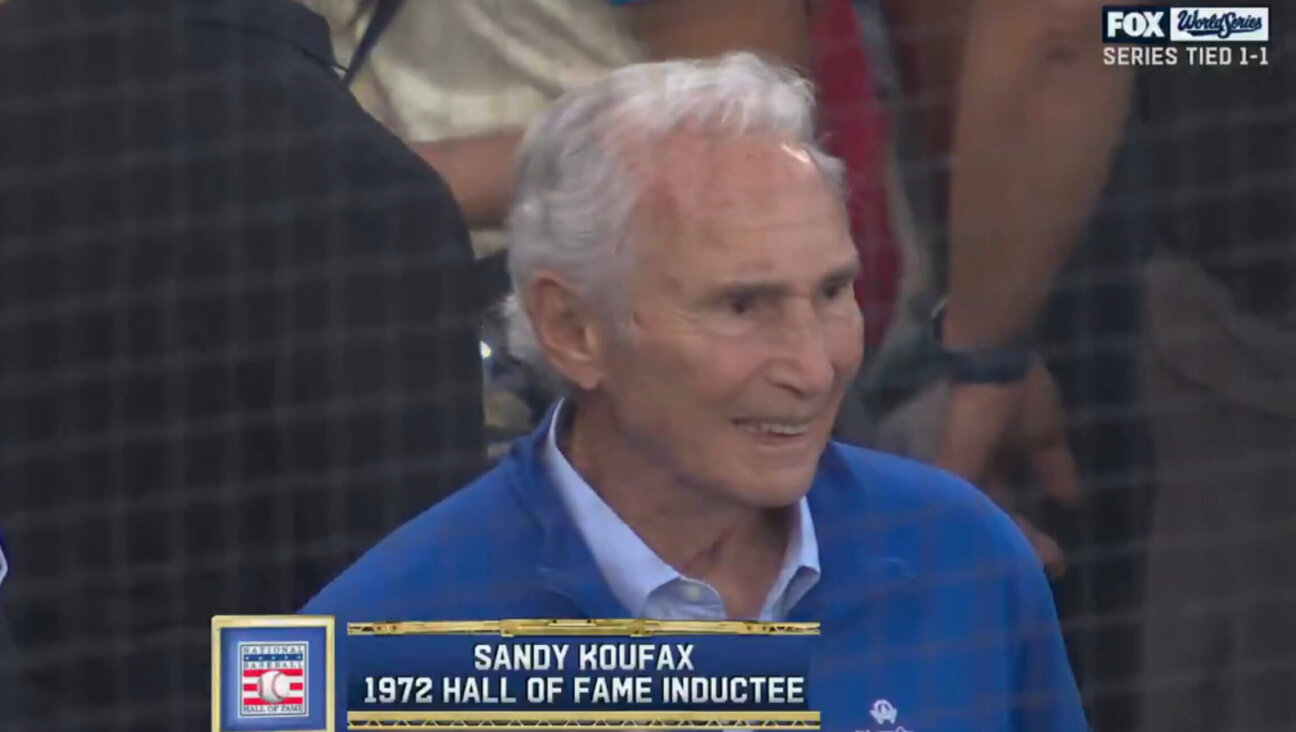

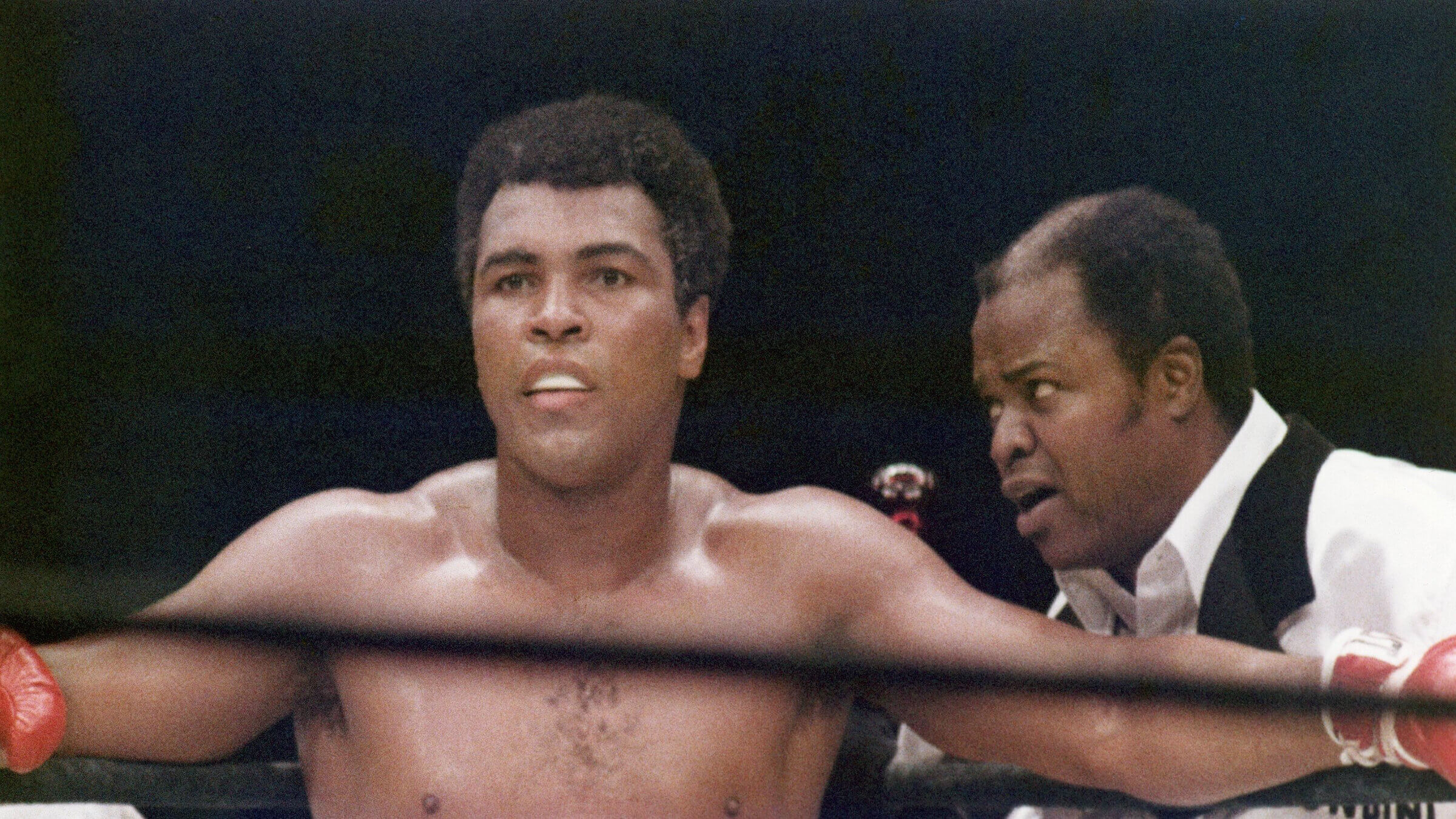

Muhammad Ali stands between rounds next to cornerman Drew Bundini Brown during the heavyweight championship against Earnie Shavers at Madison Square Garden on Sept. 29, 1977. Robert Riger/Getty Images Photo by Robert Riger/Getty Images

When Muhammad Ali dominated the world of boxing in the 1960s and ’70s, he had a Jewish friend in his corner. Literally.

Drew Brown was Ali’s assistant trainer, cornerman, “spiritual adviser,” and the author of some of his famous lines, including “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

He was born Drew Brown Jr. to a poor Black family in Florida in 1928, and later acquired the nickname “Bundini,” which is how he is mostly known.

He married a Jewish woman in the 1950s and converted to Judaism. At the time, many people frowned on intermarriage between Blacks and whites, and when the couple asked a guard at the information booth at Miami City Hall where they could get a license, the guard replied, “You mean a dog license?”

“No, a marriage license,” Bundini said.

He took some flak from Black people too. In 1964, Ali had converted to Islam and was a follower of the Nation of Islam, and some of Ali’s advisers criticized Brown for having a white wife. He resisted pressure to join the Nation of Islam, rejecting the teachings of its leader Elijah Muhammad, especially his contention that white people were devils.

“Does that mean my son is half-devil?” he would ask Ali, according to Bundini: The Documentary, based on the book Bundini: Don’t Believe the Hype by Todd Snyder. Brown was exiled from Ali’s camp, but would eventually return.

His son, Drew Brown III, who became a Navy pilot, told Snyder, “Growing up, I never once thought of myself as less than. My parents, if anything, taught me that I was better. I had the Black side and the Jewish side. I had the best of both worlds.”

In the 2001 movie Ali, Jamie Foxx portrays Brown, remarking in one of his more memorable lines, “Now I’m Jewish and he’s Muslim, and because of that he tells me I need to give up certain things, like pork and white women … I can give up the pork, but the white women? God damn, how the hell do you do that?” (Bundini acted in several movies himself, including Shaft and The Color Purple.)

Famed sports broadcaster Howard Cosell once asked Brown, “Curiously, Drew, you’re not a Muslim, are you?”

“No I’m not, Howard,” he replied.

“Well, how do you account then for the closeness of your relationship with the champion?” Cosell asked.

Brown said religion didn’t have anything to do with it. “I think we’re very close being human,” he said, adding, “I pray my way, and he prays his way, but I think we agree on a lot of points.”

A young adventurer

He took a circuitous route to become the boxer’s motivator. At 13, he joined the Navy at the beginning of World War II, lying about his age to enlist. According to one version of how he got his name, when his ship pulled from an Indian port, some girls on the dock yelled, “Bundini! Bundini!” – which he said meant “lover,” and the sailors on the ship gave him that lifelong nickname. He pronounced the name “Boodini,” with the first “n” silent.

“They didn’t find out my real age until three years later,” Brown once recalled. “By then I got my nickname in India. By then I’d been all over the world. Nothing fleshes out a man like traveling.”

Brown, who also served in the Merchant Marines, moved to Harlem as a young man, where he became a fixture in the jazz community and befriended James Baldwin and Miles Davis. He met his future wife, Rhoda Palestine, described by the documentary as “a rebellious white Jewish girl from Brighton Beach, New York,” and the couple would often go to hot spots in Harlem.

Before teaming up with Ali, he worked with another famous boxing champion, Sugar Ray Robinson.

“I couldn’t teach the champ to deliver a blow,” Brown said. “No man could do that. But I can talk to him about other things.” He worked for Robinson for seven years.

‘Boxing’s best duet’

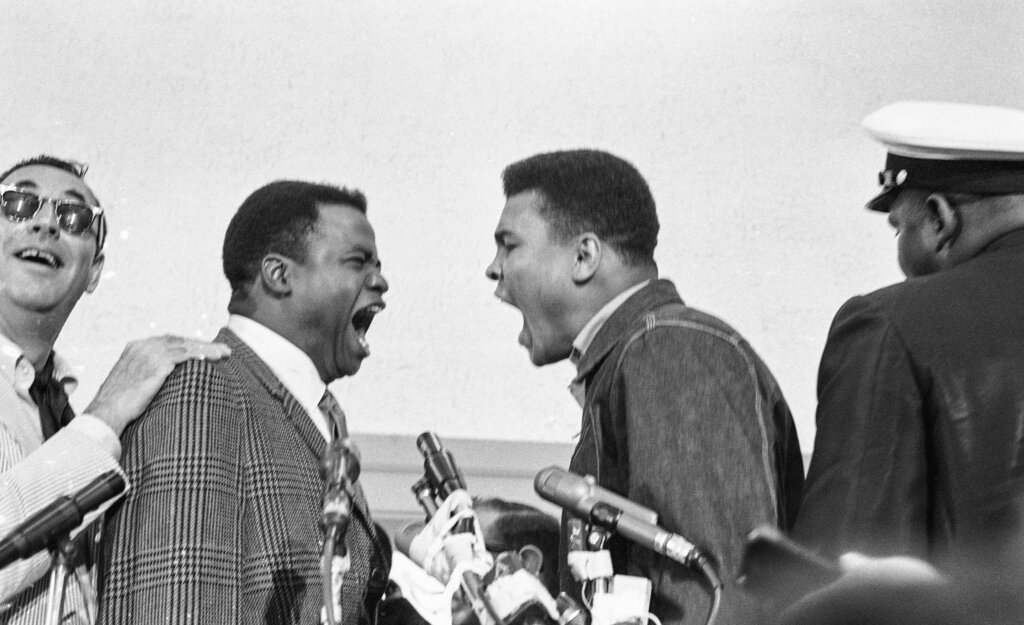

Robinson recommended Brown to Ali in the early ‘60s, when Ali was still known as Cassius Clay. As Robinson recalled it: “I saw Muhammad on television reciting poetry in Greenwich Village — that was no way to train for a fight. The next day I told Muhammad he needed somebody to watch over him, somebody to keep him happy and relaxed. I had just the guy for him. His name was Drew Brown, but he called himself Bundini.”

Brown was more than just a corner man. ESPN called him Ali’s “lyricizing, philosophizing, spiritualizing, right-hand man in the early days.” He was also known as the boxer’s personal poet and confidence man.

“Drew charged Muhammad’s battery,” recalled Angelo Dundee, Ali’s longtime trainer. “He knew Muhammad, he was great for Muhammad.”

In a 1987 New York Times column shortly after Brown’s death in his late 50s, Dave Anderson called him and Ali “boxing’s best duet. Before or after a sparring session, or when the television cameras were on, or whenever the occasion called for some noise, Muhammad Ali and Drew (Bundini) Brown would shout, ‘Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. Rumble, young man, rumble.’ After a pause, they would roar, ‘Aaargh,’ and break up in laughter.”

Brown told Sports Illustrated in 1971 for a profile headlined “Bundini: Svengali in Ali’s Corner,” that he’d get sick before Ali’s boxing matches. (The term “svengali” can have antisemitic connotations, but the profile was positive.)

“I feel like a pregnant woman,” he said. “I give the champ all my strength. He throw a punch, I throw a punch. He get hit, it hurt me. I can’t explain it, but sometimes I know what he’s gonna do before he even knows it. Some of my duties with the champ, anybody could do – use the watch, carry stuff, all like that. Other things couldn’t nobody else do because I don’t even know how I do them myself.”

Ahead of Ali’s famous 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman in Zaire, Brown said, “Remember what I said: God set it up this way. This is the closing of the book. The king gained his throne by killing a monster, and the king will regain his throne by killing a bigger monster. This is the closing of the book.” Ali won the fight to reclaim the heavyweight title.

Brown’s marriage to Rhoda Palestine lasted just six years. According to Snyder’s biography, when he died decades later, he was penniless. Ali couldn’t make the funeral because he was out of the country, but he sent a card and flowers with the message, “You made me the greatest.”