(Almost) Everything You Knew About The Polls And Israel Is Wrong

Why do Gallup and Pew polls find such different levels of U.S. support for Israel?

Why are Gallup and Pew finding such different levels of U.S. support for Israel? Image by Nikki Casey

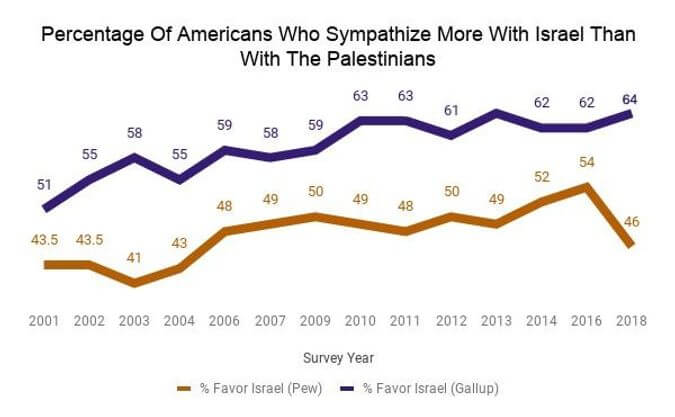

In January, the Pew Research Center released a shocking survey, which found that support for Israel among Americans had plummeted.

For the first time in 14 years, only 46% of Americans sympathized with Israel more than with the Palestinians. There was much hand-wringing among pro-Israel groups, and former peace negotiator Dennis Ross called the findings “worrying for anyone like me that cares about the US-Israel relationship.”

But then, just two months later, Gallup released a decidedly rosier poll. The Gallup poll, unlike the Pew poll, found that “Americans Remain Staunchly in Israel’s Corner.” The poll found that a full 64% of Americans sympathized with Israelis more than the Palestinians, and found levels of support that were 8 percentage points higher for Republicans and a whopping 22 percentage points higher for Democrats.

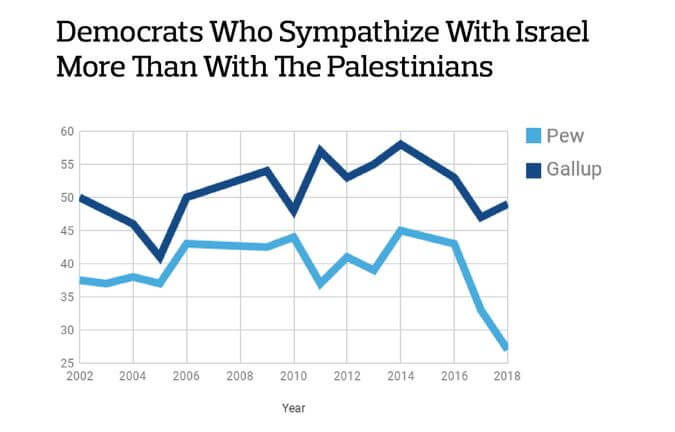

Most drastically, Gallup found that sympathy towards the Israelis among Democrats was at roughly the same level it had been since 2002. But Pew found a seismic cratering: support for Israel tanked by 13 percentage points:

Much of the gap between Gallup and Pew’s 2018 results can be explained by the Democratic respondents Graphic by Laura E. Adkins

It was an astounding difference for two polls on the same subject executed just months apart. And yet, this is far from the first time the two organizations have found dramatically different levels of support for Israel. Historically, Gallup has found American sympathies towards Israel to be about 12 percentage points above what Pew has found, though these 2018 numbers represent one of the largest divergences yet.

What could possibly explain this tale of two surveys? The characteristics of the different sample groups certainly play a role. But more importantly — and more disconcertingly — subtle differences within the surveys themselves, rather than with those taking the survey, are very likely influencing the results.

In other words, taking the results of either one of these surveys as gospel is dangerous — because the results of both are suspect.

*

It’s tempting to think that the phrasing of the questions might have resulted in this radical difference in numbers. Gallup asks, “In the Middle East situation, are your sympathies more with the Israelis or more with the Palestinians?” Pew asks, “In the dispute between Israel and the Palestinians, who do you sympathize with more, Israel or the Palestinians?”

Dr. Tamara Cofman Wittes and Ambassador Daniel Shapiro, writing for the Atlantic in January, indeed speculated that Pew’s question was flawed. Asking about “the dispute between Israel and the Palestinians,” rather than about Israel on its own, is a “misleading framing [that] reinforces an existing problem: that ‘Israel’ is conflated in the public mind with ‘the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,’” they wrote.

But Gallup’s question also frames the question about Israel in relation to the conflict, which means that Wittes’ and Shapiro’s concerns would apply equally. In other words, the difference between the questions is not enough to explain the radical difference in findings.

A more enticing explanation for the different levels of sympathy toward Israel between the two polls lies in the political and religious makeup of the random samples in each survey. Speaking to more individuals from a group that’s vocally supportive of Israel will obviously lead to the conclusion that overall levels of support for Israel are higher. And indeed, this seems to be, at least in part, what happened. Republicans are generally more supportive of Israel. And while Pew spoke to a similar percentage of Republicans (26% of their sample compared to 28% of Gallup’s), Gallup’s sample was 46% Republican when you include those who say they “lean” Republican, compared with only 38% of Pew’s — a significant difference.

Furthermore, Pew’s sample also included a larger percentage of Democrats. 33% of those they spoke to were Democrats, versus 27% in Gallup’s sample. When you include those who leaned Democratic, the number rises to 52%, versus 44% in Gallup’s — also a significant difference.

The many Republicans in Gallup’s survey certainly account for some of the difference between the two overall results. But by far the biggest reason for the dramatically different poll findings likely comes from a different area entirely: the order of the questions in the survey itself.

*

The Gallup survey question about American sentiment towards Israel was not the single question in a stand-alone survey. Rather, it was just one portion of their larger annual World Affairs survey, which they have conducted each February since 2001.

The World Affairs survey asks a series of questions — 21 in fact — about foreign and domestic issues before getting around to asking about Israel. In Pew’s survey, Israel follows an even longer list of questions — 35 in total — but the questions are largely centered on domestic policies, like Congress and President Trump, rather than on international affairs.

And it is these preceding questions that most likely account for the major differences between how Pew’s respondents and Gallup’s respondents view Israel.

This is a phenomenon known as order effects, and it has plagued researchers for probably as long as polling has been around.

In an often cited Cold War era experiment, researchers asked half of respondents whether they were willing to allow communist reporters into the United States. Only 37% of respondents said they were willing to allow the journalists into the country. But these results were completely overturned if the researchers first asked whether U.S. reporters should be allowed into Russia. Then the results nearly flipped, and a full 73% of respondents said that Soviet journalists should be allowed into the U.S.

Order effects seem to be the culprit here, too. In the 2018 Gallup poll, the question about sympathies towards Israel is immediately preceded by the question, “Looking ahead twenty years, which one of the following countries do you expect to be the world’s leading economic power?” In the 2018 Pew poll, however, the question is immediately preceded by two questions about Russian involvement in the 2016 election and about Robert Mueller’s investigation of the potential involvement.

In other words, when you ask people about Israel after asking them questions about foreign policy, they seem to like it a lot more than when you ask them about it after asking them about President Trump — especially if they’re Democrats.

Furthermore, in Gallup’s poll, there are 10 other questions on foreign policy that come before the question about Israel, as well as 7 questions about U.S. domestic policy and 3 questions about President Trump. In Pew’s survey, the question is preceded by no foreign policy questions and a slew of questions about Congress (10), Trump (over a dozen) and the Mueller investigation.

The order of these questions seems to have influenced how the respondents thought about the subject matter.

Due to the intense politicization of Israel and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in recent years, the litany of questions about Trump and Congress that Pew asks in their survey could be priming Democrats to report that they favor Israel at lower rates in Pew’s poll than they report when responding to Gallup’s poll and could push those who claim they “don’t know” or sympathize with both or neither party to take a side.

“The more questions that might create polarization beforehand, the more likely you are to see a difference,” Dr. Shibley Telhami, director of the University of Maryland Critical Issues Poll, told me.

It also confirms what, writing in these pages, Michael Koplow argued: that Israel has become tainted by Trump.

“The Mueller question in particular seems relevant in thinking about why Democratic support for Israel is so much lower” in the Pew poll, Dr. Lauren Prather, an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of California, San Diego, told me. “I think it’s perfectly reasonable to say that the question of U.S support for Israel hasn’t been politicized along partisan lines in the same way that it has been recently,” she added.

Indeed, much of the gulf between Gallup and Pew’s 2018 results can probably be explained by the polls’ 22 percentage point difference in support for Israel among Democrats, which was exacerbated by the order of questions.

Notably, the Pew study was conducted in early January, the same month that Trump threatened to cut aid to the Palestinians and barely a month after President Trump’s divisive decision to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, contributing to a marked increase in violence on the threat to cut aid in late January, by the time Gallup’s poll was conducted, the embassy issue was likely less fresh in respondents’ minds.

Prather also emphasized that news events which connect Trump to Israel could prime survey respondents to think of Israel in a more partisan light, and possibly explain some of the stark partisan divide: “Trump is such a lightning rod of partisan politics — anything he touches becomes partisan.”

*

That the questions preceding the Israel question could influence how respondents answered about Israel is further evidenced by differences between two different Gallup polls, as a senior editor at Gallup pointed out to me. For when Gallup asks people about Israel in a standalone survey, they tend to like Israel a whole lot less.

Between 2001 and 2003, the three years in which Gallup asked the Israel question both in a standalone survey and in their World Affairs survey, Gallup’s World Affairs survey found sympathies towards Israel to be about 7 percentage points higher, on average, than in the other polls conducted in the same year by Gallup, Lydia Saad, a senior editor at Gallup, told me.

These standalone surveys still found higher levels of sympathy towards Israel than Pew did over the three-year timeframe. But Gallup’s standalone survey results were much closer to what Pew found during the same time period — Gallup’s standalone surveys found levels of sympathy towards Israel that were an average of only 4.83 percentage points higher than what Pew found, nearly within the survey’s margin of error, rather than 12 percentage points higher in their World Affairs Survey.

Pew and Gallup are both well aware of the danger of order effects. A representative from Pew confirmed that “questions in the survey could have some impact on the results,” and directed me to Pew’s stance on the importance of question order in questionnaire design. Saad likewise agreed with my assessment that order effects are a key reason for the difference, stating that “the explanation is most likely going to relate to survey context.”

And yet, both Pew and Gallup’s World Affairs surveys maintain the same question order year after year for consistency’s sake.

Even worse, though, is something else that the surveys share.

In an ideal poll, survey administrators rotate the response order. For example, half of a group might be asked, “…who do you sympathize with more, Israel or the Palestinians?” while the other half is asked, “…who do you sympathize with more, the Palestinians or Israel?”

This is done to control for response order effects, which are factors that can influence a respondent to choose a certain option based solely on the order in which it was presented. In phone surveys, research indicates that people are slightly more likely to select the last thing they hear more often than other options, which is known as the recency effect, explained Dr. Jon Krosnick, a Stanford professor and winner of the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

But contrary to polling best practices, neither Pew nor Gallup rotate the response order, meaning the question is always phrased such that “Israel” precedes “Palestinians.” According to Krosnik, this could indicate that both polls slightly underestimate the support for Israel. “Most likely, if the order were to be rotated, Israel would get more support,” he told me.

Dr. Dahlia Scheindlin, a public opinion expert and an international political and strategic consultant, called this “probably the most shocking thing I’ve heard of in the history of polling. If they’re always asking Israel first, the entire thing could be a bluff.”

For their part, Pew maintains that they don’t rotate the response order because they’ve never done so, and keeping the same method each year allows one to make meaningful comparisons between their own data points. A representative from Pew’s team told me, “In order to best track change over time, we typically preserve the way questions have been asked in the past.” Gallup only confirmed that they don’t rotate the response order, and didn’t provide any further reasoning.

So does Pew or Gallup’s polling data more accurately reflect U.S. support for Israel? That’s a difficult question, and perhaps the wrong one.

As Wittes proposed in the Atlantic, the bigger issue is not whether or not Americans sympathize more with one side or the other, but whether they support Israel as a strategic ally — and both Pew and Gallup’s data, as well as Telhami’s own polling through the University of Maryland, indicate that they overwhelmingly do.

Both Pew and Gallup’s data provide a good understanding of Republican support for Israel as well as overall U.S. support for the Palestinians. Republicans overwhelmingly sympathize with Israel, and fewer than 1 in 4 Americans sympathize with the Palestinians more than with Israel.

But polling is messy and humans are fickle, and making conclusions from just this year’s two data points is dangerous. While the dramatically different results may have made for good political fodder and punchy headlines, they should not be weaponized or dictate policy. Comparing the long-term trends in both Gallup and Pew’s results shows that support for Israel can rise and fall with the political tide.

At the end of the day, the results of both surveys tell us more about the topics that trigger our deeply-rooted biases than about our feelings towards the conflict.

Laura E. Adkins is the Forward’s deputy opinion editor. Contact her at [email protected] or on Twitter, @Laura_E_Adkins

Correction, May 1, 3:37 p.m.: An earlier version of this piece misstated the percentage of the sample who leaned or identified as either Democrat and Republican in Pew’s survey. 52%, not 53%, leaned Democrat or identified as a Democrat while 38%, not 35%, leaned or identified as a Republican.