A Muslim and a Jew face the Bible Belt: Meet the only two doctors in Alabama providing gender-affirming care to trans youth

Their work is under assault by the Alabama legislature, which recently passed a law criminalizing trans health care

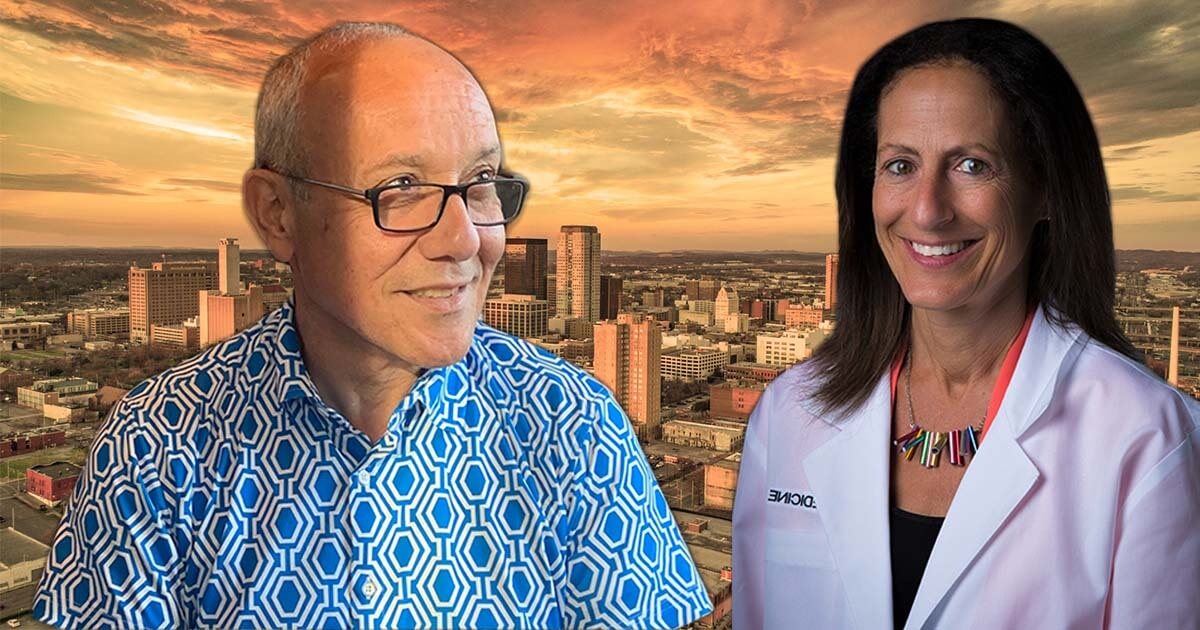

Dr. Hussein Abdul-Latif and Dr. Morissa Ladinsky are the face of transgender youth health care in Alabama. Courtesy of Dr. Hussein Abdul-Latif & Dr. Morissa Ladinsky, cityscape graphic by iStock.

There is just one clinic in the state of Alabama providing gender-affirmative medicine for trans youth, and it is jointly run by two pediatric endocrinologists — one doctor who is Muslim, and one who is Jewish.

It has not been easy providing care for trans youth in a deeply conservative (and Christian) state like Alabama. Despite the challenges, these doctors have successfully treated hundreds of patients for gender dysphoria, most of whom were referred to the clinic directly from the psychiatric unit after suicide attempts.

All that changed in early May, when the state criminalized the discussion of gender identity and sexual orientation in elementary schools, students ages K-12 using a bathroom that does not correspond to their biological sex, and the administration of puberty blockers and hormones “for the purposes of attempting to alter the appearance of or affirm the minor’s perception of their gender” to persons under the age of 19 by medical professionals.

With a stroke of the pen, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey made it a felony for doctors to provide care to trans youth, meaning the providers could face jail time for practicing medicine.

Barely a week later, a federal judge put an injunction on this part of the law, allowing medical providers to prescribe these medical treatments for minors.

I recently spoke to the two doctors about what their work has been like since then, what practicing gender-affirming medicine is like in the Deep South, and the effect bills like these have on trans youth.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What have the last several months been like?

Dr. Morissa Ladinsky: This bill has honestly been years in the making.

What was unprecedented is that this act issued a felony charge for any physicians using evidence-based, guideline-driven standards of care to alleviate gender dysphoria.

Dr. Hussein Abdul-Latif: During the one week the law was in effect, Morissa prepared for the court cases and hearings while I filled prescriptions for up to a year’s supply of the estrogen and blockers, and six months of injectable testosterone so that our patients wouldn’t have to do without.

We discussed sending some of our patients to Atlanta or Nashville to ensure they had no interruption with their medications in the long term.

Ladinsky: Hussein was working 14-, 15-hour days, making sure each patient had refills set before the law took effect.

Abdul-Latif: Some patients didn’t show up to clinics, even though we still held them as normal. One family told me that they were afraid to come to the clinic because they felt it would be more traumatic for their kid to come and to hear that our work had been criminalized.

Speaking to families who have concerns about their child’s care is easier than trying to address lawmakers. Families are usually concerned about a particular point, whereas these laws are coming from all directions. Lawmakers will come up with any excuse they can.

Ladinsky: This bill in Alabama was not an issue elevated by constituent concerns, and does not address a true threat to public safety. As doctors, we’ve been practicing this medicine for decades, and now we face felony convictions for providing care.

What is it like speaking to families who are apprehensive about what all of this means, or to whom the concept of being trans is new?

Abdul-Latif: I think parents are very comfortable in general with puberty blockers, but they certainly have reasonable worries about the long-term effects of testosterone or estrogen, that if their child changes their mind, the effects desired now to treat their gender dysphoria may not be desired in future. But I have yet to have a patient experience the desire to “detransition.”

Oftentimes, a family’s hesitation or worry about having a trans child stems more from, “How will my religion, and my congregation, view this?”

How did you each get into this work?

Abdul-Latif: Twenty-five years ago, I would have families come to me and ask, “Can you test the hormones of my kid? They’re saying they’re a boy or a girl.”

These were always very awkward visits: I would examine the child, and there was nothing pathologically different about them in their sexual organs, but clearly, there was something going on. I would do the test, and tell their parents I don’t find anything wrong.

Until one patient, maybe 13-14 years ago, was referred to me who came out as trans. The girl came with her mother, who was armed with documentation from her daughter’s therapist and the latest medical journal articles on transgender youth. Her child was not yet in puberty, but at the age when it usually begins.

I began learning everything I could. I started her daughter on puberty blockers, and maybe two or three years ago, she had surgery and completed her gender journey.

That trans child brought another and another and another. By 2015, the population of transgender youth I was seeing was growing very fast. In a meeting with the new chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Alabama [at] Birmingham, I told him that this population of trans kids that I’m seeing is growing rapidly, and asked him, “Where do I go from here?”

He suggested I start a clinic, and told me he had the perfect person to be my partner … his wife.

Ladinsky: I had been a front-line community-based pediatrician in Cincinnati, and I was seeing kids with deep dysphoria. When they would come in for their annual checkups, and we had to examine their sexual organs, they would freeze up completely. I was seeing chronic mental health issues and health conditions that stemmed from anxiety and depression around an issue of gender dysphoria I wasn’t yet aware of.

Then there was a very public suicide of a trans girl, Leelah Alcorn, in Cincinnati in 2014. She died walking in front of a truck on a highway I took every day to work.

Her suicide note was posted online within hours of her death, and it went viral, resonating with kids across the state. I took care of many kids from her area, and when I read her note, I realized that all of the issues I had been seeing in kids had a name — gender dysphoria. I realized we need to do these kids justice.

Leelah died by suicide right as I was getting ready to relocate to Birmingham, and I get a call from Hussein asking if I wanted to set up an interdisciplinary transgender health team. I said, “Oh hell yes.”

Hussein is beloved in this institution — he’s won numerous teaching awards — and through him, I’ve learned how to lead a clinical team. Our clinic’s team now includes us, a pediatric adolescent gynecologist, a psychologist and a chaplain, and most importantly, we have created an environment where each person’s professional opinion is valued equally. That makes the outcome for our patients better when, as their doctors, we have the safety to debate, discuss, teach and learn from each other.

How do your individual backgrounds influence your work?

Ladinsky: We are raised as Jews to always be using any advantage we have to work alongside the marginalized among us, and even put ourselves on the line to underscore their wholeness, their health, their ability to enjoy what life has to offer.

Abdul-Latif: Issues of transgender treatment and management are generally accepted by Muslim scholars. Culturally, it’s still very difficult and taboo, but generally, religious scholars find a way to accept it.

Islamically speaking, being trans is better than being gay if you are trans in a binary way, meaning that you transition to become a trans man or trans woman and fully adopt the gender presentation of the sex you’re transitioning to. For people who identify as nonbinary and not wholly male or female, it is more complicated.

Like most religions, including Judaism, faiths prefer a binary. I have some understanding of Islamic legal thinking, so if I have to, I can stand on it if I am challenged on my work, but it doesn’t really come up.

Both of you are non-Christians practicing gender-affirming medicine in a majority Christian population. What is that like?

Ladinsky: I didn’t realize the depth of the differences between Judaism and Islam versus Christianity until I moved to Alabama.

Here in the deep, deep South, the “Bible Belt” term really conveys the essence of the Christian belief system: that the words on that page are the words of God, not mutable, changeable or interpretable in any other way.

This is a very foreign space for both of us, whose traditions share a sustained textual inquiry, and it’s very painful to witness sometimes. It makes our job harder working with families around the gender journey, as they’re navigating a loss of hope that they cannot realize who they are without losing their faith community.

It’s not a surprise that divisive cultural wedges take root in conservative, Republican, religiously homogeneous states where the words on the page matter in such a literal way.

Abdul-Latif: We come from traditions with pretty sophisticated mechanisms of interpretation that have lasted for thousands of years. So the challenge that we may deal with in relatively young churches is the acceptance of the literal Bible, but without the depth of history of interpretation to navigate it.

Ladinsky: Here in the South, the literal nature of the Christian Bible affects everything, including how families interact. If you disagree or behave in such a way (i.e., being gay or trans), you’re going to have to make sure it’s hidden and not seen by others in your faith community.

This was really jarring for me, and I realized what a big deal it is to grow up as a Jew, where the words on the page of the Torah are derived from an oral tradition and we have centuries of practice in interpreting and aligning its teachings with modern society.

Abdul-Latif: Morissa and I are at a disadvantage because we’re not Christian and we are working with a majority Christian population. There is a diversity of thought among Christians that we have to educate ourselves on, and that’s where our chaplains come in. They understand more where the various Christian interpretations are coming from on trans people, so if they don’t have the answer for one of our patient’s families, they can find someone to help us and reach the answer.

I have to accept my limitations. I need to respect where they come from and not argue too much. I don’t have the right to argue in a religion that I don’t belong to.