I discovered a long-lost relative who survived the Holocaust in Soviet gulags

Jews who survived under Stalin rather than Hitler are largely absent from mainstream film and literature

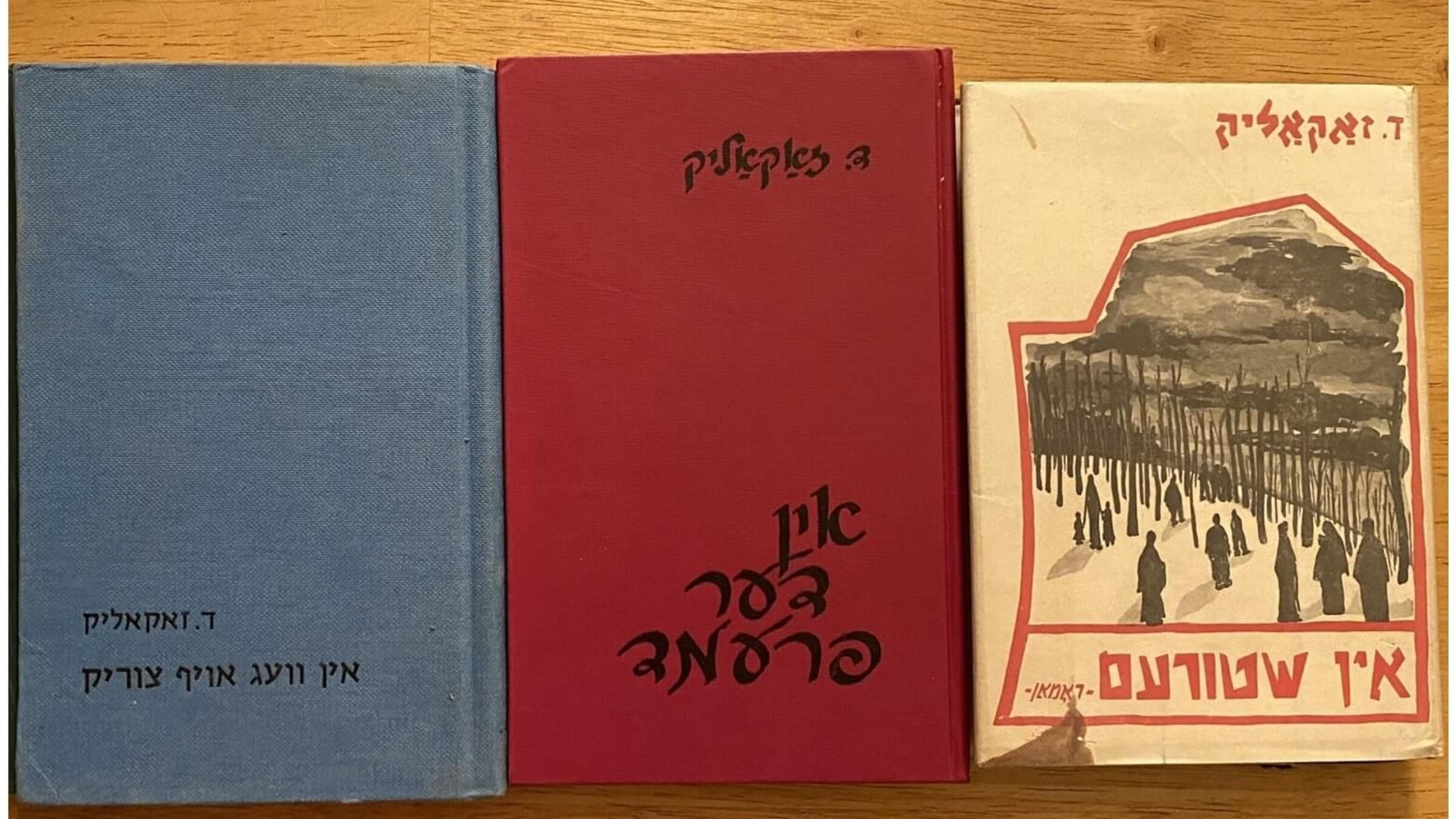

Duvid Zakalik’s Yiddish trilogy of autobiographical novels, cataloging his survival in the USSR during World War II. Photo by David Zakalik

The message was one word: “Relative?”

I stared at the Facebook message Asya Vaisman Schulman, a Yiddish scholar, had sent me. It was a biographical sketch of a Yiddish author by the name of Duvid Zakalik — the same name as me.

Duvid was born, like my great-grandfather, in the Polish shtetl of Łuków (“Likeveh” in the local Yiddish dialect). Using Yad Vashem testimonials from members of my family and from Duvid himself, I determined that his Zakaliks and mine are, in fact, branches of the same family tree originating from the Polish shtetl of Kotsk, though our exact relation is as yet unclear.

Duvid published eight Yiddish books over the course of his life, including two novels in Warsaw in the early 1930s. Then came the war, his own experience of which he didn’t write about for almost two decades.

Unlike his wife and daughter, and most of his family, Duvid escaped the German occupation and crossed the Bug River into Soviet territory, and he survived the war there. Duvid was one of several hundred thousand Polish Jews to do so. Yet his was the first such story I had ever come across, despite a strong Jewish education.

There are many Jews like me who have relatives that survived the war by escaping to the USSR. But despite a recent resurgence in scholarly interest, those who survived under Stalin rather than Hitler are largely absent from mainstream literature, and even more so from English-language television and film. Scholars aren’t even sure what to call this population: Survivors-by-exile? Holocaust escapees?

Few English-language accounts by these Polish Jews have been published by mainstream publishing houses, despite a plethora of Yiddish-language testimonials and memoirs. Duvid himself recounted his wartime experiences in a trilogy of autobiographical novels published between 1963 and 1975, which I found digitized on the Yiddish Book Center’s website. Their Yiddish titles translate to: In a Storm, In a Strange Land and On the Road Back.

Critic Yisroel Emyot, reviewing the second book in the Yiddish Forverts in 1968, noted that there were already “many, many” such accounts written in Yiddish — so many that he didn’t need to list them. So how had I, half a century later, never read one in Yiddish or English?

Polish scholar Magdalena Ruta noted more recently that a large corpus of such accounts in Yiddish needs to be compiled, and that among literature of the gulag, of exile and of totalitarianism in general, Yiddish-language accounts “are still waiting to become part of that discussion.” These Jews’ cultural obscurity is all the more striking because they’re the largest group of Polish Jews to survive the war. Australian sociologist Jonathan Goldlust calls this phenomenon a case study in cultural amnesia.

There are many complex reasons for this silence. Scholars of the Holocaust describe a “hierarchy of suffering” in which the Holocaust naturally dwarfed the Soviet experience in cruelty, brutality, privation and horror. Even those who’d spent years in the gulag often felt a need to keep quiet. Historian Eliyana Adler notes that those who had accepted Soviet citizenship, or who’d had it forced upon them, were afraid this would prevent them immigrating to the U.S. Many Holocaust survivors had also been liberated by the Red Army and much of the world wasn’t ready to hear about the horrors of Soviet communism in the immediate post-war period.

Still, the rarity with which such accounts have been translated out of Yiddish is astounding, despite a robust community of Yiddish literary translators working today. The overwhelming majority of Yiddish literature — an estimated 98% — remains untranslated. I hope soon to make Duvid’s trilogy available in English, as his story of survival, taking him across the USSR, is worth sharing with a wider audience.

Duvid fled Nazi-occupied Warsaw in November 1939 for the relative safety of Soviet-occupied eastern Poland, leaving behind his wife and daughter. The following spring, he and thousands of other Polish refugees were deported to the gulag or to forced labor settlements. He survived backbreaking labor and starvation in unimaginable cold. After being granted amnesty and Soviet citizenship following Hitler’s invasion in 1941, Duvid and thousands like him traveled across Central Asia looking for work and bread. He and other Polish Jews were repeatedly rejected from, then finally accepted into, the Polish Army. He reached liberated Lublin in 1944, where he found Christian Poles running shops confiscated from Jews. He recalls them crossing themselves at the sight of him. In Lublin he learned that of all his family, only a brother in Tel Aviv remained alive.

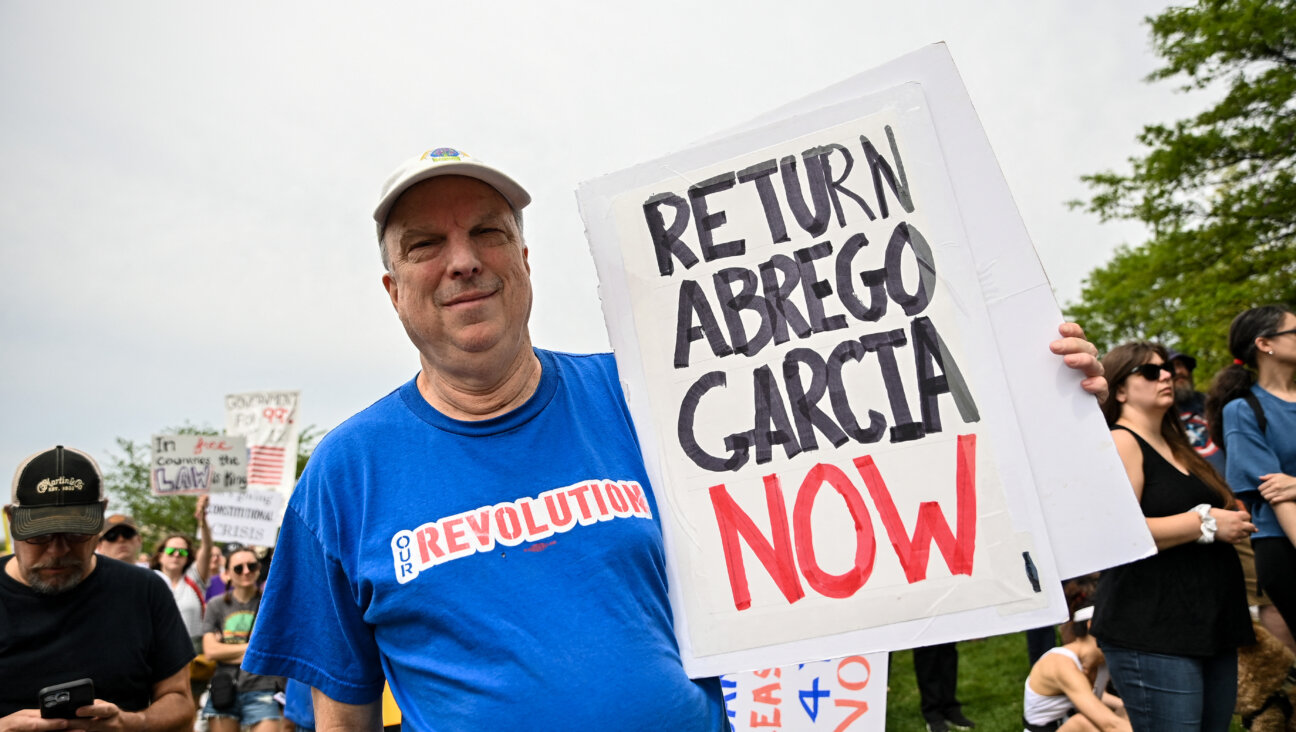

The themes explored in accounts like Duvid’s — the betrayal of refugees by a supposedly tolerant government, cultural erasure, forced labor and religious persecution, territorial annexation through sham elections — are sadly as salient today as ever. Yet historical memory is politically contentious, and it can feel like a zero-sum game. Though decades of self-silencing by Polish Jewish escapees still undoubtedly has a strong effect, contemporary politics may also have a role.

The history of communist repression, like the history of Nazi oppression, risks exploitation today by right-wing nationalist governments such as those of Hungary and Poland, who seek to whitewash their countries’ histories of antisemitism and collaboration with the Nazis. Accounts by more left-leaning authors such as Duvid, or his friend and companion Avrom Zak, might run this risk of being used as a vehicle to condemn socialist and liberal policies. Gulag memoirs by more left-leaning authors such as Duvid, or his friend and companion Avrom Zak, might run this risk as much as accounts by right-wing Jews like Menachem Begin or Julius Margolin.The Soviet regime’s crimes against Jewish refugees also complicate Russian national myths surrounding the Great Patriotic War — the Russian name for World War II — which makes stories like Duvid’s doubly politically volatile.

The obscurity of survivors-by-exile means that the largest group of Polish Jews to survive World War II is largely absent from mainstream understanding of Jews’ fate during the war. As the number of Holocaust survivors dwindles with time, so will the number of survivors-by-exile and native Yiddish speakers. There is, then, a certain urgency in translating more accounts like Duvid’s out of Yiddish now, however fraught today’s politics may be in the background.

History and politics aside, Duvid’s writings are first and foremost a link to an entire branch of my family I never knew, a branch largely destroyed by the Nazis. Family, the most arbitrary and primal connection humans experience, transcends the political. It cuts across the loyalties increasingly demanded by ideology, class, party and tribe. It is the enemy of totalitarianism, and I am proud that my relative, Duvid, left a record of his struggle.

To contact the author, email [email protected].