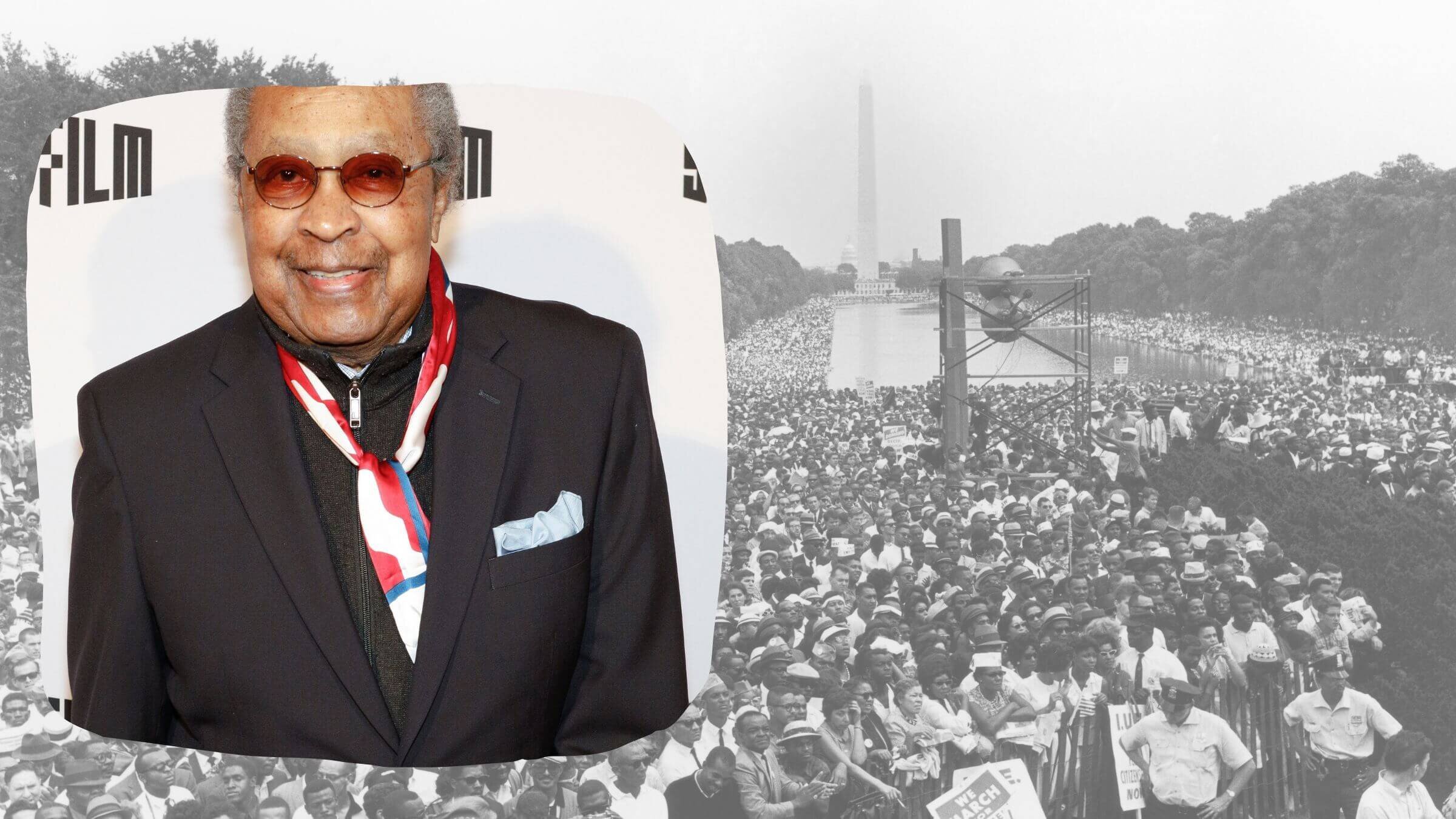

Clarence Jones helped MLK write speeches. He’s still fighting for Blacks — and Jews

Clarence Jones invokes the contributions of Jews in the Civil Rights Movement

Graphic by Nora Berman; Kimberly White/Getty Images

At 92, Clarence B. Jones has been a powerful force in the racial equality fight for decades. But his latest activism stems from watching white supremacists marching with tiki torches in Charlottesville in 2017, chanting, “The Jews will not replace us.”

“I said, ‘Oh yes they will, l because I’m going to help!’”

Jones, a member of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inner circle from 1960 until the civil rights leader’s 1968 assassination, served as legal counsel on everything from responses to segregationists’ libel suits to bailing King out of a Birmingham jail. He also wrote several passages of the “I Have a Dream” speech delivered at the 1963 march, and is among several speakers slated for the official celebration of the March on Washington’s 60th anniversary on Saturday — though, as he told me in an interview this week, “King didn’t need me or anyone else to write his speeches.”

Jones has documented those events and others in his recently released memoir, Last of the Lions. In it, he gives particular attention to the importance of Jews in the Civil Rights Movement — a topic that has been subject to reinterpretation, if not revisionist history. That includes suggestions that fewer Jews were involved than commonly believed and that they assisted the Black freedom struggle only out of a paternalizing self-interest.

Jones strongly disagrees.

“Absolute nonsense!” he said. Reiterating the power of the alliance and its continued necessity, he said, “We could not have done what we achieved without the support of the Jewish community.”

Shaken by Holocaust stories

Years before the march, Jones said he learned of Jews’ true motivation at another protest in a location he has since forgotten.

“I went up to a man and I said, ‘Why are you here supporting us and marching with us?’ And unprompted — like when you open a spigot of tap water in the kitchen — he said, ‘Oh, you should tell Dr. King I speak for white people of Jewish descent. My mother and my father died in the Holocaust. They put Jewish people in freight cars and gas chamber and they killed us because we were Jewish.’”

Personally moved, Jones said he did convey that message to King, reminding him that Blacks comprised only 12% of the U.S. population and needed all the allies they could get — even from a smaller population of Jews who were devoted to the cause.

Though by 1968 Jones and King needed no further convincing, another reminder of Jewish sincerity came days before King’s death at a belated 60th birthday celebration for Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel at a Catskills resort.

“Dr. King walks into the banquet hall and there are rabbis all leaning against the wall with their arms interlocked,” Jones said. “They began to sing, as a birthday tribute to Heschel, ‘We Shall Overcome’ — in Hebrew. The two of them stood in the middle of the floor and wept.”

While that account is eclipsed by the better-known image of King and Heschel at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, holding tiny American flags, it speaks to the real kinship between the two clergy leaders. The same is true of King’s relationship with his other lawyer-adviser, Stanley Levison, a Jew and real estate investor who was one of the movement’s most important fundraisers. Just before the march, Levison was pressured out of the movement in response to FBI allegations of Communist associations in his youth.

Similarly, Bayard Rustin, the organizer of the 1963 march who had advised King since the 1955-57 Montgomery Bus Boycott, was forced out of King’s circle of advisers by Rep. Adam Clayton Powell and other Black leaders for being gay, which they viewed as a liability with the potential for blackmail.

Yet in his memoir, Jones documents his continued contacts with both men right up to the assassination. It was Rustin who urged King to come to Memphis to assist in the 1968 sanitation worker’s strike that would be his final campaign.

“Are you kidding me?” Jones told me of his continued connections to both men. “You think I’m going to let that (expletive) J. Edgar Hoover dictate who I can talk to? He can kiss my a—!

“Stanley Levison was like an older brother to me,” he continued. “Dr. King loved him, too. What Stanley and Bayard had in common was an unconditional giving in of their commitment. It’s not like they supported us in expectation they would receive anything in return.”

Rustin, Levison and King are long gone, and Jones’ appearance at the next week’s commemoration comes not as a representative of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, but as chairman of Spill the Honey, an organization seeking to enhance the coalition between African Americans and Jews, as well as members of both groups.

(Full disclosure: I too have been asked to advise Spill the Honey, following the release of its 2020 documentary film Shared Legacies that includes extensive interviews with Jones. I was asked for suggestions on better representing the activism of African American Jews and invited to join the board. At first I declined — but when told Jones was the chair, said hell yeah!)

Turning 93 next January, Jones knows this is his final act. But should he get an encore, he knows exactly how he should be cast.

“When I die, I’m coming back Jewish,” he said.

But still Black, I asked?

“Absolutely!”