60 years later, a Jewish volunteer at the March on Washington remembers ‘the most peaceful of days’

Growing up in the wake of the Holocaust, Harvey Burg committed himself to civil rights

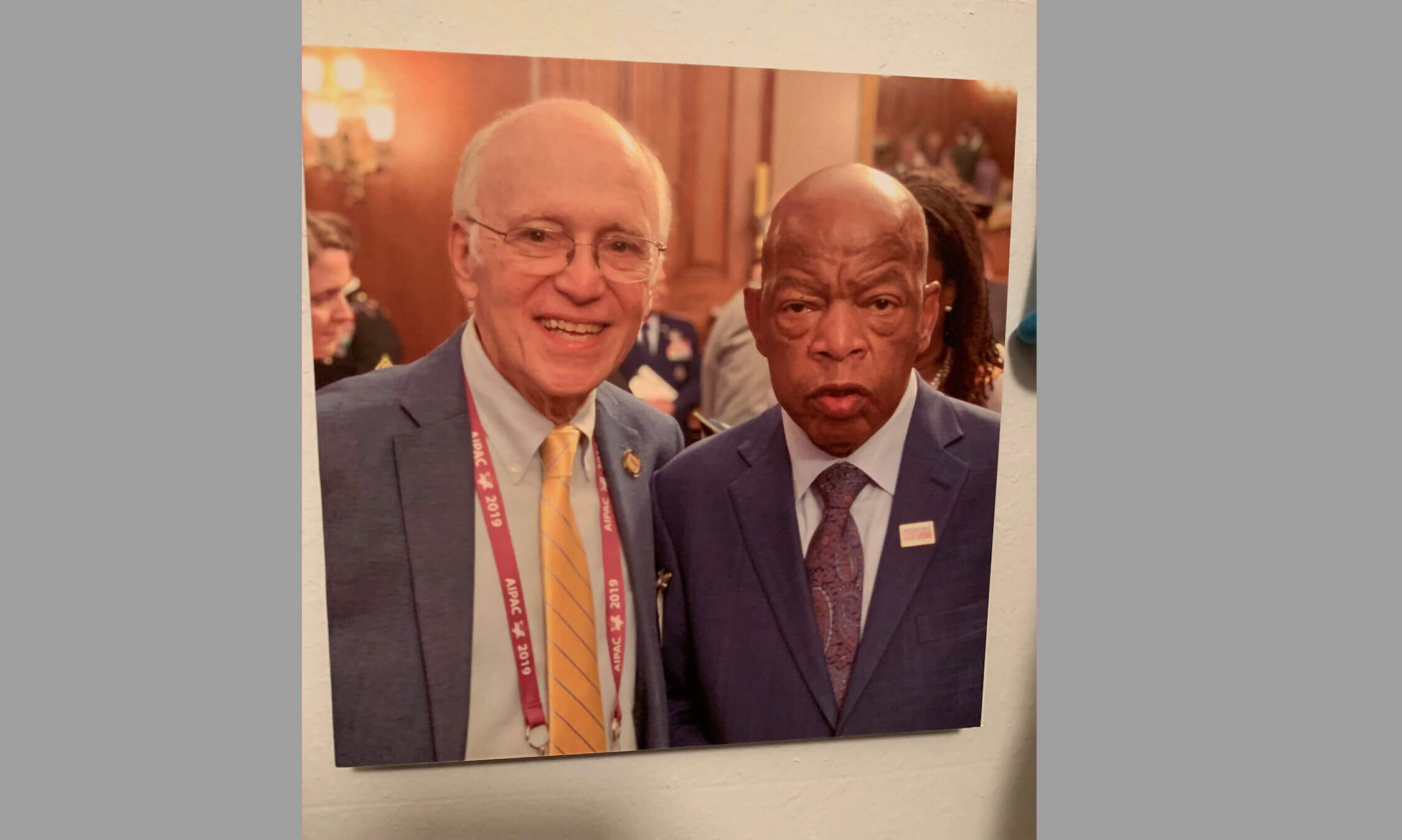

Harvey Burg, left, with his friend, the late Congressman John Lewis. Courtesy of Harvey Burg

Harvey Burg was a 22-year-old interning at the State Department in August 1963 when he saw a call for volunteers. There was an upcoming civil rights demonstration on the National Mall, and the organizers sought people who were familiar with Martin Luther King Jr.’s principles of nonviolent protest to help protect marchers. He jumped at the opportunity.

“Coming out of that World War II experience as a kid, seeing people mourning with Kaddish because their relatives had been lost,” Burg said. “It was quite natural to be involved with the March.”

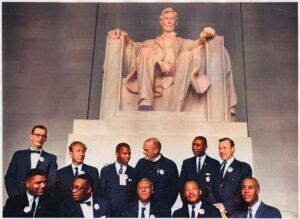

He was one of about 90 armband-wearing volunteers — per his recollection — who staffed the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was held 60 years ago this Monday. He estimated he was about 100 to 200 feet away from King as he delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech.

For Burg, who later became a partner at the first integrated law firm in Alabama, the March was far from his first taste of the fight for civil rights. As a college student at University of Pennsylvania, he was arrested for disrupting a picket organized by George Lincoln Rockwell, of the American Nazi party, of the film Exodus. Burg got to make a call from jail, but “being a Jewish kid,” wanted to spare his parents worry so didn’t mention his whereabouts.

I asked Burg, who lives in Austin, Texas, to reflect on his experience about the March.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you want to be a part of the March on Washington?

I did not want to live in a country that discriminated on the basis of characteristics with which we were born. Coming out of that World War II experience as a kid, seeing people mourning with Kaddish because their relatives had been lost, all of that made an impact. So did my time in West Africa, which I explored when I was in college. I came to understand and appreciate the incredibly rich culture of the African people. I learned about slavery, and recommitted to the idea that race and religion shouldn’t matter in how people are treated.

Did you see a lot of discrimination growing up?

I was born in the Bronx and when I was 9 my family moved to Long Island — maybe a mile from the site of the original United Nations. Living that close to the U.N., I went to school with kids of different races and played soccer with them. We would talk about this stuff in high school. Being born Black was like being Jewish — you couldn’t do anything about it. It’s hard to articulate it, but knowing what happened to us as Jews by the Nazis, I didn’t want to live in a society that discriminated.

What was the volunteer opportunity and how did you hear about it?

March organizers like Dr. King, John Lewis and A. Phillip Randolph were concerned that there could be violence. So they asked the Rev. Walter Fauntroy to put together a group of marshals who understood the meaning of nonviolent protest, so that we could intervene if necessary to keep the march going, and to be an intermediary if there were any clashes with the Capitol Police.

I had spent some of my off time in Cambridge, Maryland, with a local civil rights group, and I heard about the March there. I signed up, and my boss at the State Department blessed the undertaking.

I had a unique background, having spent time when I was in college in any number of countries where the yoke of colonialism was being lifted, including Ghana and Morocco, where local cultures were coming to the fore. I felt pretty comfortable as a young man. I was in good physical shape. And I had a secret weapon that did me in good stead even in hostile environments: I played soccer. I could diffuse a tense situation by getting in the game.

We trained with Reverend Fauntroy for about a week — techniques in group concentration and how to deal with it. But no one knew what to expect.

What do you remember about that day?

It was one of the most peaceful days I can remember, at any demonstrations or anything else.

I never felt ill at ease in large crowds, so that didn’t concern me at all. But all of a sudden I was like, “Oh my god. This is like Times Square!

As marshals, we never once had to intervene. This group was so respectful that we could just turn our attention toward the events. To see so many people come out and march, and determined to do it nonviolently — it was a special and spectacular time.

What was the mood like?

I think the mood was joyful. The mood was, “The time has come.”

The power of Dr. King, the emotions and the clarity of thought — it was just so moving. What was equally moving was that the crowd hung on every word. It was one of the great days of history.

One of the lines that always stuck with me was about how little Black boys and little white boys could go arm and arm to play together. That became a powerful message for me when I was practicing law in Alabama, trying to desegregate schools and institutions, to address disparities in resources between Blacks and whites, and the treatment of Blacks by the police.

The Jewish speaker at the March, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, tied it to Germany and to what we as Jews encountered there. That spoke to me. It reinforced my commitment to the Civil Rights Movement. It also made me proud, because I knew at the time of Jewish people who had come to the March by the busload.

How did that day shape your involvement in civil rights going forward?

I went on from the March on Washington to volunteer while in law school for the Law Students Civil Rights Research program. I took my first internship in Birmingham, Alabama, and kept working in Alabama after graduation. So the March on Washington was just a natural step because of my prior background, and my time in West Africa and Israel.

I later became friends with John Lewis. When I was commuting to law school, I would stop in Atlanta to be briefed as to what was happening in the field, because the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which he helped lead, was very involved in Alabama.

What do you think was achieved that day and what remains to be achieved on civil rights?

I often think about the Haggadah. When we sit down at Passover, the Seder begins with the admonition that you should tell your children as though you are coming out of the land of Egypt from slavery and you have to build your life. George Santayana said, “Those who don’t know history are condemned to repeat it.” So in every generation, we have the duty to educate, and we as Jews especially want to educate about equality.

I have been very excited to see the millions of demonstrators in Israel, people coming out for principles of equality, tolerance and all those things that are part and parcel of the civil rights values. That gives me great hope. And it’s happening here, too, with the Republican opposition to abortion rights having reawakened a younger generation to the important principles of getting engaged. I’m always hopeful because in our system, we can advocate for change.