How a silent meditation retreat changed my view of Yom Kippur

An estimated third of non-Asian American Buddhists have Jewish ancestry. I went to see what the fuss is all about

Photo by Laura E. Adkins/Open AI

Yom Kippur is a day many Jews associate with dread and cynicism. Until recently, I was one of them.

On top of harshly judging your questionable life choices, you’re expected to fast for 25 hours while contemplating the looming possibility of being written out of the Book of Life. For some, it’s like the Super Bowl of self-judgment.

It’s not exactly the most loving holiday. Or is it?

As these themes marinated in my mind, heightened by two years of a global pandemic, I drew a connection to another group that shares the cherished tradition of focusing on suffering: Buddhists.

It might sound like the start of a bad punchline. But the connection between Judaism and Buddhism is so strong that an entire subset of people identify as both Jewish and Buddhist, known affectionately as ‘JewBus.’ It’s estimated that as many as one-third of non-Asian American Buddhists have Jewish ancestry.

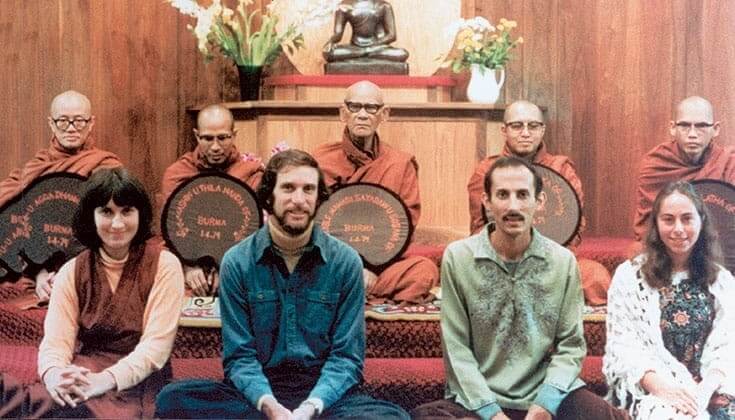

Sharon Salzberg and Joseph Goldstein may have something to do with that. They met at a Buddhist monastery in India in 1971, and the teachings they brought back to the states laid the groundwork for the modern mindfulness movement amid a countercultural spiritual revolution.

I first spoke with Salzberg over Zoom, where she shared why she took that fateful trip to India. “My mother died when I was 9, and then I went to live with my grandparents. A lot of suffering was never spoken about. Everyone thought it would be kinder not to bring it up. And so I was left in the strange world of all these feelings inside without any external affirmation. Then there was the Buddha saying right out loud, there’s suffering in life. And for me, that was not depressing. For me, that was liberating.”

Metta and meditation

Together with Jack Kornfield and Jacqueline Mandell, Salzberg and Goldstein co-founded the Insight Meditation Society in 1974, which became the first Vipassana meditation center established by Westerners in the United States.

To see what the benefits of a silent retreat are like, I made the pilgrimage to IMS during the last weekend of August. I figured If Salzberg and Goldstein could spend years roughing it in India, the least I could do was spend a weekend 90 minutes west of Boston.

The weekend retreat is what the staff dubbed “Buddhism on training wheels.” Most people come for a week, with more advanced ‘Yogis’ staying up to three months. One married couple stayed for four years.

My journey to the retreat was a meditative one. During my rainy drive to Barre, Massachusetts, I traversed miles of quiet, windy roads surrounded by lush greenery. The IMS center itself rests on a sprawling 125-square-mile plot of land off of the aptly named Pleasant Street. Mounted to the top of the building in big letters is the word “metta” — not the Hebrew word for death, but the Pali word for “lovingkindness,” which has become the bedrock of Salzberg’s practice.

True to the Buddha’s teachings, IMS aims to be a judgment-free zone where you can be your authentic self. For some, that meant wearing Crocs with socks.

If you thought this was a place for tree-hugging tofu eaters, you would be correct. The cafeteria served vegan fare, like kale and carrot quinoa soup. It was truly a cleansing weekend in more ways than one.

On the first night, we had our “letting go ritual” of “renunciation,” during which we had the option to turn our phone in for the weekend. I reluctantly handed mine over, mainly worried about keeping track of time since I didn’t have a watch. It turns out that was no problem because, at the top of every hour, a meditation bell would chime, making a soft, resounding gong sound that reverberated around the building, indicating it was time for the next session.

Noble silence

Once the retreat formally began, we entered “noble silence” for the remainder of the weekend. Entering the meditation hall felt not all that different from a Jewish congregation, except for the giant Buddha statue looming over the altar, and the stained-glass windows of Jesus that greet you in the hallway (the building was converted from a Catholic Church that left a few artifacts behind).

We were instructed to remove our shoes before entering. Instead of sitting in pews, we sat on the floor with a zabuton and a zafu, two types of meditation cushions.

Some people seemed to worship the Buddha statue with devotion, bowing down when entering and leaving the hall. But despite the iconography that abounds, IMS focuses on mindfulness stripped of metaphysics and cosmology.

There was no talk of Nirvana or rebirth. The emphasis was entirely on the Buddha’s ethical mindset toward humanity and nature with mindful exercises for cultivating stillness and presence.

My experience in the meditation hall closely mirrored that of another legendary Jewish meditator, Sylvia Boorstein, who first visited IMS in 1977. Now 87, she told me when she sat down in the meditation hall for the first time, she started silently chanting, “Hineh ma tov uma na’im, Shevet achim gam yachad”’ — behold how good and how pleasant it is to sit among kin.

While I didn’t have the same urge to chant Talmudic verses in my head, I did feel a warm familiarity of being in “noble silence” with close to 100 others fully locked in focus. In a sense, it wasn’t all that different from reciting the silent Amidah, except that instead of standing, we were sitting.

An introvert’s oasis

As I adjusted to the vibe, the retreat soon became an introvert’s oasis in a world of chaos. Mornings started at 5:30 a.m., which was surprisingly not difficult — It’s amazing how refreshed you can feel when you haven’t fried your brain with bright screens all day.

My retreat was led by the teacher Narayan Liebenson. She guided us in meditation, speaking in a serene voice with a measured cadence full of intentional pauses. Wearing a white robe, she knelt between lit candles with purple and pink flowers on either side of her and a Buddha statue looming over her from behind the platform.

She led us in a Metta practice of ‘lovingkindness’ in which we silently repeated phrases like “May I be happy, may I be healthy, may I be free.” You start with offering these words to yourself, then to another person in your mind, and ultimately to all beings.

This practice isn’t all too different from the Mi Sheberach, the Jewish prayer for healing an individual or group of people.

The most impactful lesson instilled in us was to have “less wanting and more being” and to remember that “no one is less than or better than.”

After the retreat, I got the chance to meet Sharon and Joseph in person at their home, a large duplex which sits atop a forested hill. The two native New Yorkers, both in their mid-to-late 70s, have lived in Barre ever since they opened IMS. I was taken by their humble demeanor and down-to-earth nature.

After 50-plus years of doing this work, and more than a dozen books published, they animatedly discussed these topics with no ego whatsoever. I was welcomed with the warmth of extended family despite only having spoken with them a few weeks prior. (Both were pleasantly surprised to hear that the Forward still exists, having grown up on the Yiddish paper.)

Neither Salzberg nor Goldstein are observant Jews, but both maintain their pride in being Jewish as an intrinsic part of their identity. This year, Salzberg plans to observe Yom Kippur by tuning into a livestream of New York’s Central Synagogue’s service led by Rabbi Angela Buchdahl. She says the two have become friends through Buchdahl’s interest in mindfulness. Every Tuesday, Buchdahl records a Torah-inspired meditation.

Goldstein left me with a piece of wisdom I’ll never forget. “Attachment is wanting things to stay a certain way, and commitment means hanging in there through all the changes,” he said. “The more we see impermanence, the less we’re attached because it’s like trying to hold on to a waterfall. It’s impossible.”

A day for focus and compassion

After my weekend of silence, I’ve come to see Yom Kippur as Judaism’s annual day-long meditation retreat. The real power of Yom Kippur isn’t self-judgment through religious ritual. It’s in using your mind to enrich the parts of your life you need to work on. The Buddhist principle of accepting the present moment instead of putting up resistance to life’s external factors might seem counterintuitive at first. Only once you accept your reality with self-compassion can you find the inner resolve to move forward with clarity and insight.

Much like the retreat I was on, Yom Kippur is a day for adjusting our relationship with the past to be a better version of ourselves in the present. Just like in meditation, this change in perspective is achieved through cultivating a more compassionate mindset.

As Sylvia Boorstein told me, “It doesn’t matter what building you walk into and what words you say. It has to do with what is the intention of your mind and heart. And my intention is to cultivate a mind that has compassion for all beings.”

Yom Kippur can be a framework for getting us on the right track — or, as the Buddhists call it, the right “path.” In both traditions, there’s an emphasis on being present, healing pain and adjusting our relationship to past events — especially those that have caused suffering to ourselves or others.

Both Yom Kippur and meditation aim for us to live in greater harmony with ourselves and others. Through cultivating self-awareness, we can replace self-loathing with self-respect. Instead of clinging to negative feelings, we can gently acknowledge them before letting go. When you deepen your self-compassion, you deepen your love of self and others. It’s why Sharon Salzberg says, “love isn’t a feeling, it’s an ability” you cultivate, much like a skill.

A more mindful Yom Kippur

In much the same way, Yom Kippur can be an inflection point for making powerful changes in our thinking.

In that sense, Yom Kippur is a state of mind. It’s a day of reconditioning ourselves to become present and whole.

It’s easy for division and discord in the world to cloud our soul and corrode our inner being. Through self-awareness, we have the tools to realign ourselves.

In the past, I had been so consumed by the solemn religiosity of the day that I had lost sight of the spirituality the holiday has to offer. The intentions we set through self-reflection pave a path for personal liberation — and that can be obtained anywhere.

If Yom Kippur is a time you’re typically zoning out on auto-pilot, maybe this reframing of the day can activate your sense of purpose. It’s not called the “days of awe” for nothing.

Now, Yom Kippur feels more like a group meditation session that I look forward to rather than a day of suffering I despise. I feel a deeper sense of presence and inner spaciousness than I ever had before. It’s like my mind is fully hydrated.

Through self-awareness, we have the tools to realign ourselves. Both Yom Kippur and Buddhism offer tools to practice forgiveness, healing and letting go.

These are vital skills. Yom Kippur is Judaism’s holiday of turning inward to find the best path forward. That’s not a punishment. It’s a gift.

To contact the author, email [email protected].