In 1991, Iraq attacked. Israel’s far-right leader didn’t retaliate. Is Netanyahu capable of the same wise choice?

Israel’s decision about whether to react to Iran’s weekend attack could have massive global consequences — and the man making it couldn’t be less fit

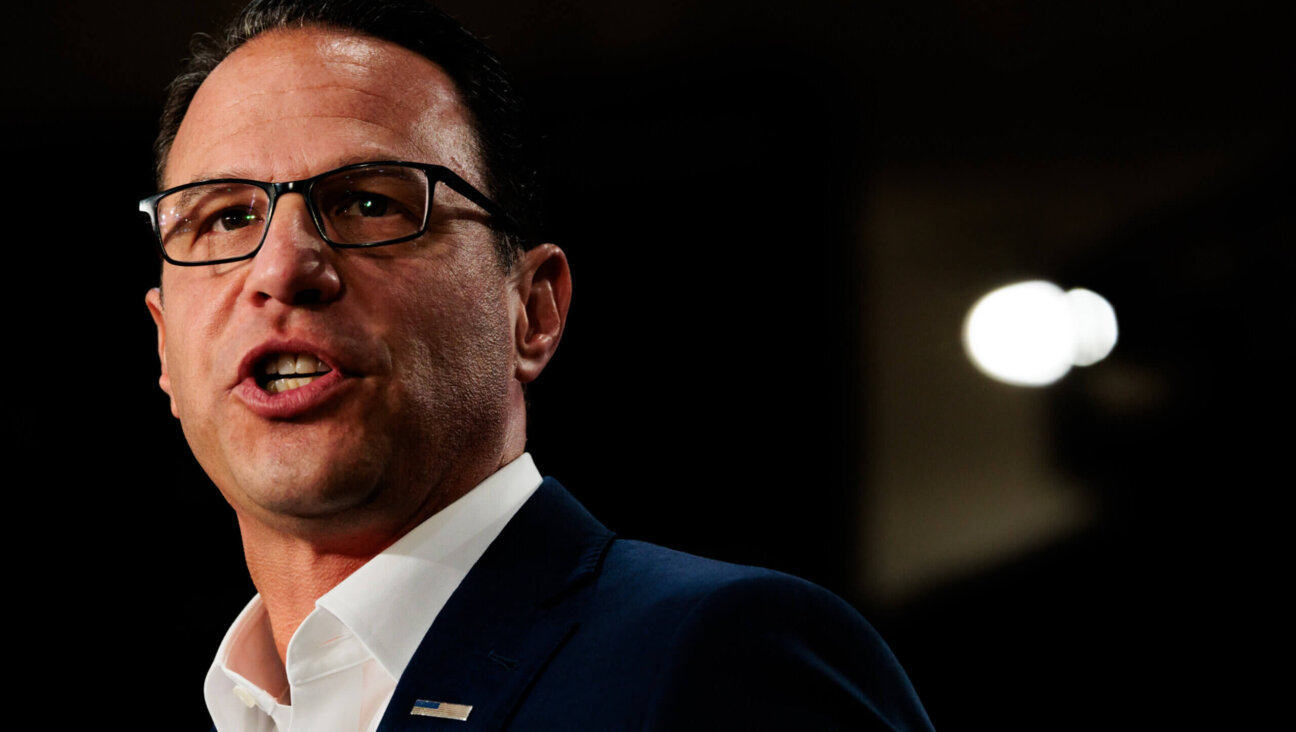

Is Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu capable of following the restrained example of a far-right predecessor? Photo by Jacquelyn Martin/Pool/AFP/Getty Images

Lawrence Eagleburger, the State Department’s No. 2 official, flew to Israel in January 1991 with just a couple of days’ notice and a singular mission: stop Jerusalem’s far-right prime minister from hitting back at Iraq, even as that country’s dictator, Saddam Hussein, rained SCUD missiles down on Israel.

I was a reporter in Israel as those missiles fell back then and will never forget the indelible image of the imposing, portly, chain-smoking diplomat emerging from his helicopter and walking gingerly, with the aid of a cane, to meet with the diminutive Israeli leader Yitzhak Shamir. The contrast between the two seemed to literally embody the heft of the U.S., then the world’s sole remaining superpower, ready to sit on its smaller ally to restrain it from disrupting one of the most astonishing military coalitions in history.

It was a moment bearing striking similarities — but some equally striking differences — to the moment now facing the U.S. and Israel in their tight but fraught relationship following Iran’s weekend attack on Israel.

In response to the assault of some 300 drones and missiles — approximately 99% of which were intercepted by missile-defense systems — several key Israeli leaders are howling for blood. Israel, said National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, must now “go berserk” in order “to create deterrence in the Middle East.” His far-right cabinet colleague, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, echoed the sentiment.

Cooler heads in the inner war cabinet now running Israel’s military campaign in Gaza have seconded President Joe Biden’s recommendation of de-escalation with the conclusion of Iran’s attack — one that caused no deaths and minimal damage, thanks to a spectacular display of U.S. and Israeli defense technology. Terming the result “a strategic achievement,” war cabinet member Benny Gantz urged a continued focus on Gaza over retaliation against Iran. “We must remember that we have yet to complete our missions,” he said. “Most importantly, returning the hostages and removing the threat from residents of Israel’s north and south.”

The crucial question mark remains the stance of Israel’s leader, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Back in 1991, Saddam’s aim was to draw Israel into joining a war already in progress against him — and thereby blow up a U.S.-led international alliance that included many Arab and Muslim adversaries of Israel with armies already on the battlefield.

Under the leadership of President George H.W. Bush, countries such as Syria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Pakistan and Oman were fighting alongside America, its NATO allies and a set of former Soviet bloc countries to combat Saddam’s invasion and annexation of the Persian Gulf state of Kuwait. With the recent fall of the Soviet Union as a communist power, the war marked a moment of peak U.S. hegemony.

Saddam’s SCUD missiles resulted in significantly more damage than the drones and missiles that Iran launched toward Israel Saturday, which caused no deaths and minimal damage. By the time Eagleburger arrived, the bombardment from Iraq had already killed 30 Israeli civilians.

But if Israel retaliated, as it initially vowed to, Bush’s grand alliance was likely to splinter into pieces, mid-war.

To convince Israel not to respond, Eagleburger brought gifts. The first arrived several days before he did: multiple batteries of the Patriot missile defense system, then the world’s state-of-the-art surface-to-air technology. His other blandishments included 15 F-15 fighter planes, several Sikorsky helicopters and $700 million in surplus U.S. ammunition and other gear.

Most importantly, Eagleburger brought the president’s assurance that if only Israel would turn its other cheek — for the moment — America and its coalition would vanquish Saddam, and solve the problem.

Shamir, a veteran of the far-right terrorist group known as the Stern Gang, which was established prior to Israel’s founding, felt that acceding to Eagleburger’s pressure went against every principle he held. But accede he did, facing down howls of protest from members of his own cabinet. The Patriot systems helped stem the tide of SCUDs. And Bush Sr.’s coalition indeed routed Saddam’s forces, permanently ending the threat raining down on Israel from Iraq.

On Saturday, President Joe Biden organized a smaller coalition of Western forces and a somewhat quieter group of Arab countries to team up with Israel, using U.S.-funded air defense technology to successfully defend against Iran’s attack: An estimated 100 of Iran’s 300 drones and missiles were shot down before they even reached Israeli airspace. But Iran’s attack still marked a new and more direct phase of the long-running conflict between the two countries, one which Iran has until now waged through regional proxies such as Hezbollah in Lebanon.

On Israel’s side, the conflict has been a shadow war, waged without declaring responsibility: Israel has covertly killed top Iranian nuclear scientists on Iran’s own soil, spirited out top secret documents from Iran’s archives proving its drive to attain nuclear capabilities and, earlier this month, hit Iran’s consular annex in Damascus with missiles, killing top generals of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.

In a Saturday phone call after Iran launched the attack, Biden assured Netanyahu that the United States remained “rock solid” in its support and defense of Israel. He also acknowledged Israel’s right to retaliate.

But the United States, he said, would not join Israel in any offensive military move against Iran. It was a modern-day version of Eagleburger’s arm twist.

As they did in 1991, Jordan and Saudi Arabia reportedly actively aided America in defending Israel, shooting down Iranian missiles and drones over their air and sea space with U.S.-supplied hardware. The quiet spectacle of such support — in defiance of popular revulsion against Israel among those countries’ citizens — reflects something enormously important. The same is true of calls by countries such as Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar for a rapid de-escalation of the crisis. Even after Israel’s massive killing of civilians in Gaza in its response to Hamas’s Oct. 7 massacres — Israel’s campaign has so far killed an estimated 33,686 people — both Israel and Sunni Arab-majority countries seem driven together by the seriousness of the threat they perceive from Shiite Iran and its proxies.

From the start of its Oct. 7 attack, Hamas’ grand strategy has been to draw other, more powerful supporters more directly into its war against Israel. Biden’s larger aim has been to contain the war, leaving Hamas to face Israel alone. Israel gambled that its attack on Iran’s Damascus consulate wouldn’t tilt the balance toward Hamas’ goal. A harsh retaliation by Israel could still achieve that goal and defeat Biden’s.

Reportedly, Hamas never warned Iran before launching its Oct. 7 attack. And Iran told Hamas soon after that it would not join in the war with Israel. Tehran’s highly choreographed drone and missile onslaught suggests it’s still in no rush to do so. In fact, Tehran’s aggression was downright old-fashioned in its deliberate pace and style, as Iranian officials broadcast their intention to strike well in advance, gave Israel and its allies hours to deploy a response with the long flight time of its drones and missiles, and followed the attack with a formal announcement that its campaign was now concluded. Its decision to forego having Hezbollah join in with its hundreds of thousands of missiles, just minutes away on Israel’s border, underlines this.

But one big difference between 1991 and today throws into doubt any assumption that Israel’s response to Biden now will mirror its response to Bush then. That difference is Israel’s leader.

Shamir was, if anything, considered to the right of his hawkish predecessor, Menachem Begin. But no one ever doubted that his decision — whatever it turned out to be — would be totally independent from his own personal aims, and even his domestic political interests. Whether they agreed with him or not, most Israelis had faith that Shamir would make crucial strategic decisions based exclusively on his view of the nation’s best interest.

Few have a similar confidence in Netanyahu.

Israel’s current leader is currently facing a trial on serious corruption charges, with strong evidence against him. If he were to be convicted, he risks the real possibility of prison time. His entrenchment as Israel’s wartime prime minister is the main thing holding the trial at bay — for now.

Furthermore, his hold on this tenuous immunity depends on keeping together the extreme far-right coalition supporting him. They are demanding the harshest, most aggressive response possible, and defying the Biden administration is part and parcel of their appeal to their own (and Netanyahu’s) base.

Can anyone say with certainty that Netanyahu’s decision-making isn’t influenced by this? With no near-term path to ousting him democratically, Israel’s fate now lies in the hands of a dubious character confronting a choice with dangerously perverse incentives.

That has been a problem for the country since Oct. 7. Now, it’s the world’s problem, too.