Berlin Philharmonic Returns to Roots

Image by Getty Images

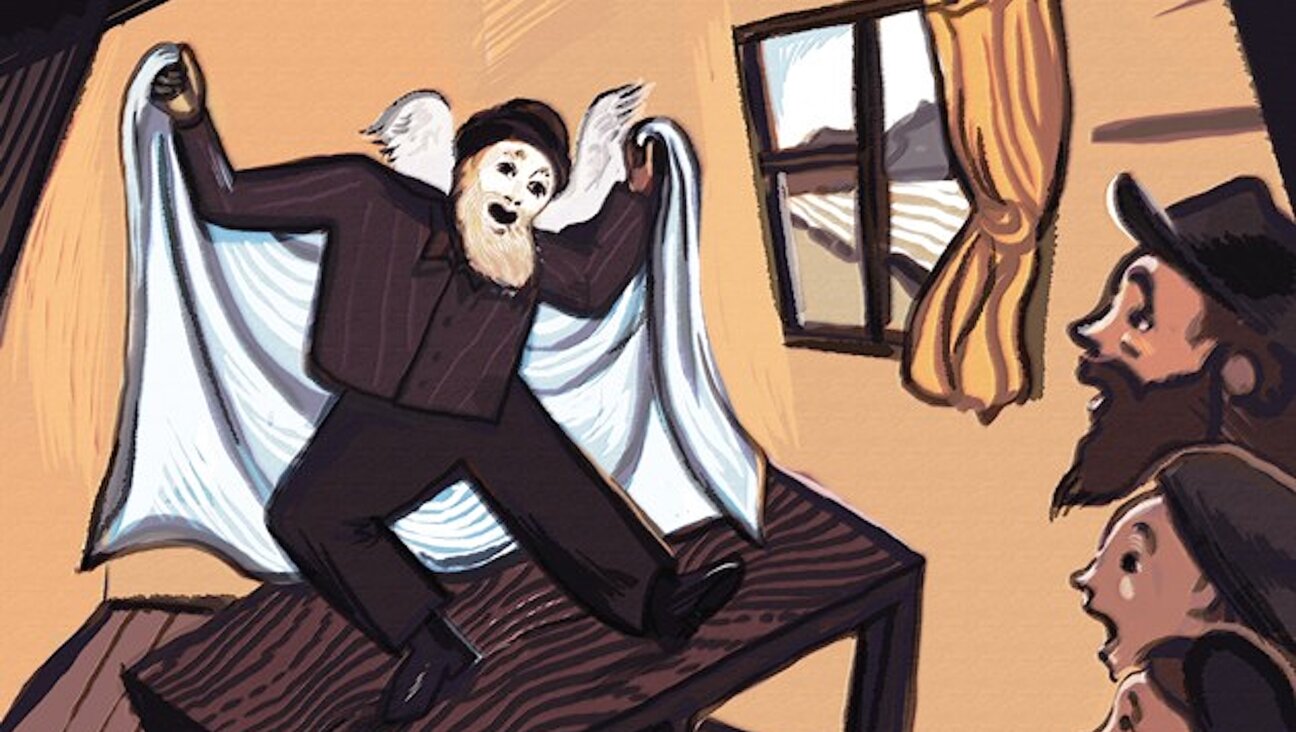

In tandem with three New York concerts given by the Berlin Philharmonic in February, New York University’s Deutsches Haus has opened an exhibition of Holocaust survivor David Friedmann’s “Lost Musician Portraits” from the 1920s. These sketches of Berlin Philharmonic members were drawn from life, and captured each of the artists in the act of performing. Before World War II Friedmann’s sketches of various personalities in all fields appeared in hundreds of newspapers, but have only recently been rediscovered. His talent helped him survive Auschwitz, where he drew portraits of SS guards, their families, and even their dogs.

The exhibit, which is also sponsored by the Leo Baeck Institute and the consulate general of Germany, includes short biographies as well as recordings of all the musicians shown in the sketches, many of whom were Jewish. It is on view until March 30. (WNYC broadcast a substantial interview about the artist with his daughter, which can be heard here.)

The Berlin Philharmonic has always been one of the finest orchestras in the world. But only since 1989, when Claudio Abbado took over from Herbert von Karajan, and more recently under the direction of its current music director, Sir Simon Rattle (whose contract has just been extended to 2018), has the orchestra once again begun to have the kind of adventurousness it was known for at the time these portraits were made. It is currently a surprisingly young orchestra — the average age of its musicians is 38 — and almost half the members are not German.

The first of the three Carnegie Hall programs, on February 23, showed off the orchestra’s range. They played four works, all from a five-year period in the 1890s, each demonstrating a radically different approach to sound. Debussy’s “Afternoon of a Faun” could hardly have sounded more luxuriant and wayward; Dvoràk’s “Golden Spinning Wheel” could not have been more middle-European and folkloric; Elgar’s “Enigma Variations” could not have been more Edwardian, and Schoenberg’s”Transfigured Night” could not have been more inward and angst-ridden.

Idiomatic Debussy and Elgar is not the kind of repertoire one expects from the Berlin Philharmonic. Their second concert occupied more of their traditional territory: Bruckner. They knocked the newly restored score of Bruckner 9th Symphony out of the ballpark, including a shockingly barbaric rendition of the scherzo, which surely would have pleased the composer.

Their series concluded with another home run: Mahler’s heaven-storming 2nd Symphony, “Resurrection,” preceded by three works for chorus and orchestra by Hugo Wolf. Mahler himself premiered his 2nd Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1895. But unlike their unbroken tradition performing Bruckner, Mahler’s works were removed from their repertory during the Nazi period, and were not played again until well after the war. Whatever links there had been were lost — much like David Friedmann’s portraits — and the music had to be relearned in recent decades. Rattle rallied the orchestra and Westminster Symphonic Choir, and they handily raised the roof with this spectacular work. (Listen to a recording of the performance here.)

The Berlin Philharmonic concerts in Carnegie Hall were made possible, as they have been for decades, by the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation. The Kellens, because of their Jewish ancestry, were forced to leave Germany, but devoted much of their substantial philanthropy to bettering relations between the U.S. and Germany.

View a slideshow of drawings by David Friedmann:

/