The Secret Jewishness of Inspector Hercule Poirot

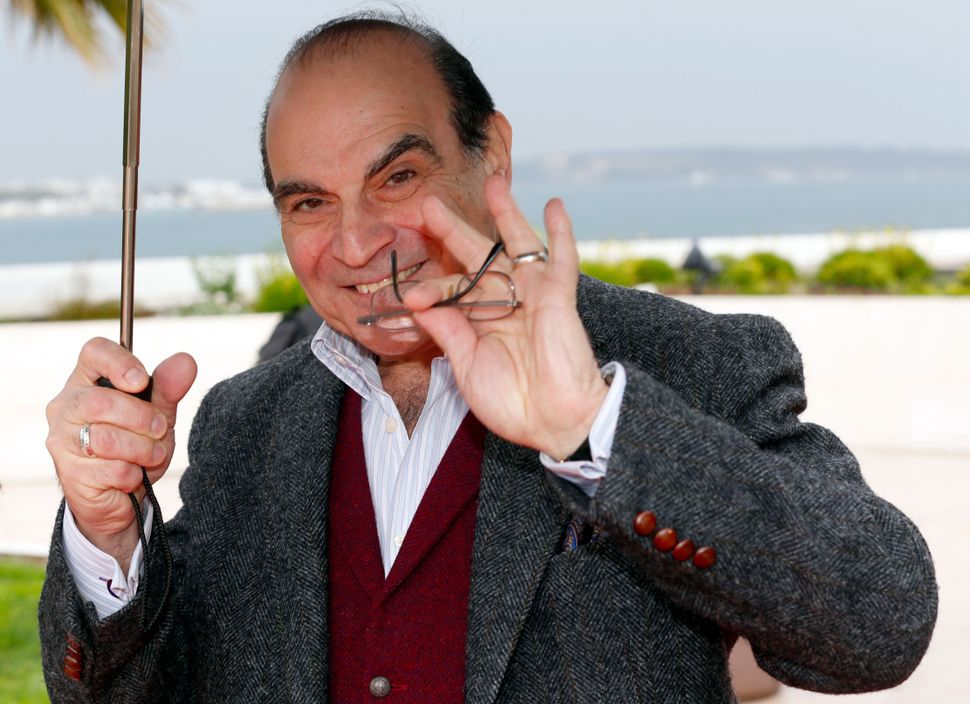

Actor David Suchet minus the Poirot mustache. Image by Getty Images

When I noticed the other day that Liz Meriwether had recommended Agatha Christie’s Poirot as an “antidote to the 2016 election” in New York Magazine back in August, I had one of those moments where you can deeply, personally, relate to an article. Here is Meriwether, on fictional private detective Hercule Poirot’s signature mustache:

“As you begin to watch the show, the mustache is so distractingly bad that you’ll find it hard to pay attention to any of the dialogue. After a while, though, you come to accept the mustache for what it is, then you find yourself needing it. You find yourself unable to go to sleep without it. The sight of Poirot’s mustache will become the signal your brain needs to know that the day is done, work is over, Trump isn’t the president yet, and you are safe.”

I too had found my way to Poirot, for no reason other than, I’d already gone through all the more exciting-seeming British murder mysteries that Canadian Netflix had on offer. I was a bit disappointed to see a Poirot-as-sleeping-pill appreciation (if delighted by the piece itself), just because nothing could be less #trending. It’s like when you learn that the worn-out old clothes you wear on weekends are actually the height of fashion.

While Poirot has earned its place in the ranks of shows whose opening music alone can induce sleep, it never quite reached Midsomer Murders levels for me, and that’s because – what else? – there’s a Jews-and-gender angle. An enormous one, and one that risks canceling out the profound low-stakes-ness of the plot-lines.

I have Googled, and my just-beyond-Wikipedia-level expertise on Poirot tells me that neither the character nor David Suchet, the actor playing him, is Jewish by religion. Suchet is, however, ethnically Ashkenazi, as am I, so this fact could well be what got me thinking along these lines. But it’s not Suchet-as-Poirot’s physical appearance, really. It’s the character. (Having almost finished Murder on the Orient Express, this would appear to be consistent with at least one of the novels.) And it’s not merely, in general terms, that the character seems Jewish. It’s much more specific: Hercule Poirot, in the show, is basically every ‘The Jew’ from turn-of-the-century literature.

Poirot’s the ultimate cosmopolitan, averse to nature, comfortable only in cities (and on glamorous cruise ships). He’s the eternal foreigner, speaking a near-flawless but accented English. He’s forever on the periphery of an international aristocracy, at those parties but never really of that world. He’s all brains and no brawn to the extreme extent that he solves one case without leaving his bedroom.* He exists in contrast to his dimwitted assistant, Hastings, who offers a posh British everyman respectability to Poirot’s London-based private-detective enterprise. Poirot is “Belgian” but in a way that seems less rooted in Belgian-ness than in, he’s from somewhere else, hint hint, and since no one knows what to expect a Belgian to look or seem like (except the handful of us who are or are married to Belgians), that’s a good nationality to pick. Whenever another character sneers at him something like, ‘You… Belgian,’ I know what’s really going on.

Then there’s the gender angle, which, if you’ve read the brilliant late historian Paula Hyman’s book, Gender and Assimilation in Modern Jewish History, you will not be able to disentangle from the Jewish one. In it, Hyman analyzes “the conflation of Jewishness and femininity in Western societies, with the consequent anxiety of Jewish men about their own masculinity.” Poirot isn’t gay, nor would he fall under contemporary understandings of gender-non-conformity. But he’s, what, effeminate? Effete? There isn’t really a contemporary word for where Poirot falls on the gender self-presentation spectrum. The only way I could put it is, you know the dude-bros who wear cargo shorts? He’s the opposite of that, in a way that would, in earlier eras, code as “Jewish.”

And he’s regularly mistrusted by other characters because he’s foreign and somehow feminine. But he’s not an anti-Semitic stereotype, exactly, because the show is, to put it mildly, on his side. While the series meets just about every item on a problematic-ness checklist, there is, in some small, coded way, a happy Jewish ending to each episode, when Poirot has brought justice not in spite of his hard-to-pinpoint difference, but because of it.

*It occurred to me that if the Proust-Poirot connection had dawned on me, surely there were volumes written on the topic. A quick search suggests… one blog comment: “David Suchet in the role of Hercule Poirot always puts me in mind of Proust for some reason. The dapper fastidious dandy who avoids contact with anything to do with the elements, yet someone who can see inside people straight away without any prejudice or blinkers.”

Phoebe Maltz Bovy edits the Sisterhood. Her book, The Perils of “Privilege”, will be published by St. Martin’s Press in March 2017.