This Boston synagogue looks like a New England church but murals reveal its Jewish identity

The hundred-year-old Vilna Shul is one of a handful that has retained its folk art-painted walls

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

One hundred years ago, synagogues for communities of immigrant Jews were dotted all over Boston. But only one of them still stands today: the Vilna Shul (built 1919) on the city’s historic Beacon Hill.

The preservation of the Vilna is particularly fortunate, since its sanctuary contains exuberant folk art murals with decorative and Jewish motifs, painted in three phases during the 1920s. (The earliest and most striking are from circa 1920). Synagogue murals like these were once popular in parts of the United States, but they’re now extremely rare. Other examples include the “Lost Mural” in Burlington, VT and the Stanton Street Shul on the Lower East Side.

These days, the Vilna is a vibrant cultural center, dedicated to protecting its unique material legacy and showcasing Boston’s rich Jewish life, past and present — including interactions with other immigrant cultures. But when the shul was built in 1919, it was an Orthodox synagogue where a large and loyal congregation assembled to conduct daily, weekly and holiday prayers. Immigrants’ children were married in the sanctuary, and members who passed away were eulogized at funeral services there.

The congregation grew out of a late-19th-century landsmanshaft — a mutual support group formed by immigrants who had been born in the same town or region in Eastern Europe. In this case, the landsmanshaft was for immigrants from Vilna Gubernia — the region around the city of Vilnius (“Vilna” in Yiddish) in modern Lithuania. Vilna and its territory had been home to a dynamic Jewish community for centuries, but Jews began to leave the area in large numbers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Usually they settled in New York, but also in smaller centers like Boston.

The Vilna landsmanshaft members lived in Boston’s West End, a thriving community mainly of Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Tragically, the West End was destroyed by a failed urban renewal project in the 1950s. But in the first decades of the 20th century, it was full of Jewish homes and Jewish-owned businesses displaying Yiddish shop signs. A Yiddish newspaper, called Di Bostoner Idishe Shtime (“The Boston Jewish Voice“) ran from 1913 to 1916 and was intended for West End readers.

At first the Vilna landsmanshaft prayed in members’ apartments. In 1906, they purchased a vacant African American Baptist church on Phillips Street, on the north slope of Beacon Hill. The Hill wasn’t part of the West End, but it was nearby, within easy walking distance. The north slope was more diverse and working-class than the rest of the Hill, which was dominated by the splendid homes of the moneyed, aristocratic “Boston Brahmins.” The north side had been largely African American since the late 18th century, and this neighborhood was a good fit for immigrant Jews.

The congregation stayed in this building until 1916, when the city paid them $20,000 to vacate so the premises could be used as a school. The community decided to use this money to build their own synagogue, also on Phillips Street. They hired Boston’s only professional Jewish architect, Max Kalman, to design it for them. Members of the congregation pitched in to help with the construction work. By 1919, the new synagogue was ready for use.

The spacious sanctuary that Kalman designed on the second floor resembles classic New England churches, with its tall windows and rows of wooden pews. But details reveal its Jewish immigrant identity — like the megillah holders still standing by the handsome Torah Ark, which are actually pickle barrels covered in red velvet. Stained glass ornaments in the doors connecting the sanctuary and the outer vestibule proudly feature multi-colored Stars of David. And mural painters (probably hired rather than from the congregation) decorated the walls and ceiling with colorful imagery.

These natives of Vilna Gubernia knew about painted synagogue sanctuaries fun der alter heym (Yiddish for “from the old country”). Their native area had once been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which had a long and rich tradition of extraordinary wooden synagogues — plain and unadorned on the outside, but a riot of painted decoration inside.

The best-known example today is the Gwoździec Synagogue (destroyed by the Nazis in 1941). Its dazzling interior decor — including zodiac symbols, animals and floral motifs — was painstakingly recreated by the Boston-based Handshouse Studio, and is now displayed at the POLIN Museum in Warsaw. Gwoździec, known in Yiddish as “Gvodzhits,” was in modern Poland, but synagogues with painted interiors were dotted all over the former Commonwealth. The founders of the Vilna Shul would have worshiped in them, or at least known about them. And when they built a new shul for themselves in Boston, they chose to recreate the vibrant and festive atmosphere they remembered from the wooden synagogues at home.

The Vilna Shul was an active and beloved neighborhood institution for decades. But with the destruction of the West End as a result of urban renewal efforts in the 1950s, and the relocation of many Jews to Boston’s western suburbs, membership gradually dwindled. On Rosh Hashanah 1985, it was impossible to assemble a minyan. The shul doors were locked and the building stood empty and neglected for the next 10 years.

In 1995, a small but determined group of Bostonians purchased the decaying building. They set to work raising funds to stabilize the structure and make it safe to enter. At some point before 1985, the sanctuary walls had been painted a uniform beige, and the ceiling a light blue, covering over the murals (which had likely gone out of fashion). The team that started working on the building in 1995 had no idea that there was anything noteworthy underneath the bland coats of paint. It was only during structural inspections in 1998 that the first traces of vivid folk art were discovered.

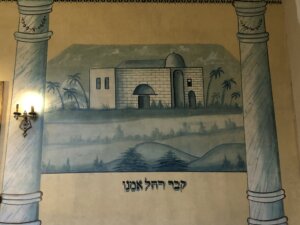

Ongoing research and conservation since 1998 has revealed three layers of murals, each separated by a coat of beige paint. The first phase from about 1920 was the most ambitious. The ceiling and walls were covered in vivid floral and architectural motifs, with at least one large Star of David at the back. Most of these original images are still hidden by later overpainting. But the wall of the women’s section (on the same floor as the men’s section) has revealed two large scenes in shades of light blue: The Tomb of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs in Hebron, and the Tomb of Rachel in Bethlehem. The second and third phases from the later 1920s seem to have been more modest, and survive only in some fragments on the walls. The ceiling retained its original decorations until they were covered at an unknown date with blue paint.

The team at the Vilna plans to reveal and restore everything that remains of the earliest murals. Ongoing fundraising will support this project, and also help with installing lights and a sound system for educational presentations in the sanctuary. In the meantime, the vestibule outside the sanctuary has been fully restored. The walls are painted the same warm mustard-gold as in 1920. A striking oil painting of a rabbi donated by famous Boston Jewish artist Hyman Bloom — who worshiped at the Vilna Shul as a boy — has been installed. Blue flowers from the original phase of decoration encircle the spot where the chandelier attaches to the ceiling.

Even after 28 years, the team at the Vilna is still uncovering its hidden treasures and learning more about its rich history, making its immigrant Jewish past come alive for visitors in Boston and beyond.