A short Yiddish horror film set at the start of the Hasidic movement

Informed by Jewish folklore and the writings of Isaac Bashevis Singer, the film carries a mythic poetic quality

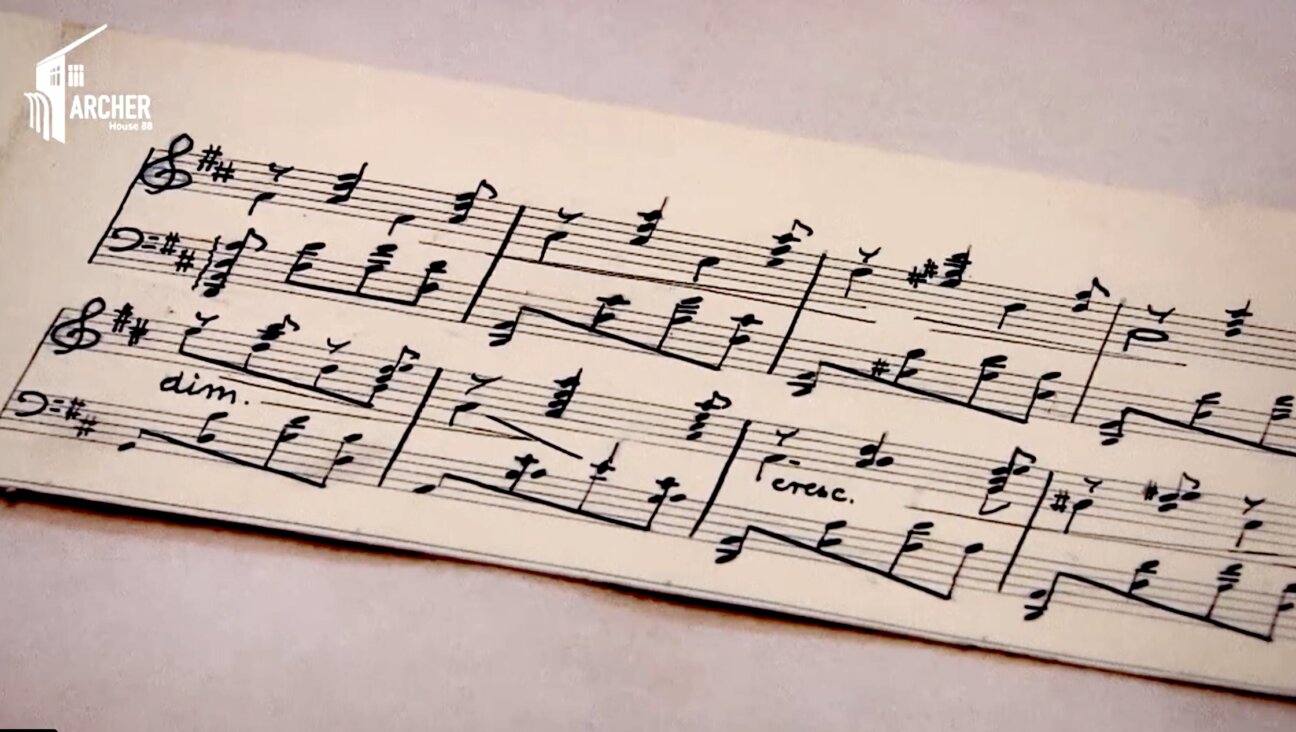

Courtesy of Daniel Daniel

Seed of Doubt, a short, Yiddish-language horror movie making film festival rounds, raises two thought-provoking questions: What makes a horror movie horrifying, and how does that change when the film is in Yiddish?

The film, called Kerl fun sofek in Yiddish, is set in an 18th-century Polish shtetl during the beginnings of the Hasidic movement. Hadassah (Elizabeth Connick), a young woman in late pregnancy, is reeling from the recent death of her husband. In the wake of the tragedy, Hadassah finds herself doubting her faith, leading her concerned parents to invite the local rabbi (Edmund Dehn) to intervene.

But when the rabbi sits down with her and proposes a renewal of faith to fend off possible demons, she spits in his face and hurls obscenities. He warns that her unborn child’s fate is at stake. After the failed intervention, the film portrays Hadassah’s transcendent and ecstatic mystical awakening.

Although Seed of Doubt is just 20 minutes long, it portrays a young woman’s religious and moral doubts in a superbly acted and visually arresting narrative. It is not to be missed.

The “shtetl-folk-horror film,” as writer-director Daniel Daniel calls it, emerged from his own search for meaning growing up in a tight-knit Modern Orthodox community in London. Informed by Jewish folklore and the writings of Isaac Bashevis Singer, the film carries a mythic, fairy-tale, and poetic quality. Although Seed of Doubt takes place several centuries ago, it feels fresh in its treatment of Hadassah’s desperate search for meaning amid adversity.

The primary audience for Yiddish horror movies — and there are enough of them now to call it a subgenre — is not today’s Hasidic communities, who use the language every day. It’s primarily non-Yiddish speakers who rely on subtitles. The creators of these films, who are likewise not Yiddish speakers, work closely with dialogue coaches or consultants to make the Yiddish dialogue happen. The London-based Yiddish researcher Izzy Posen translated the script and coached the actors not only to speak Yiddish, but to do so in dialects and speech styles to match their characters’ education and worldviews.

“Telling the story in Yiddish shifts the lens through which we experience the film,” Daniel said in a recent interview. “It adds a folkloric texture. In English, the film would have felt too modern and immediate. Yiddish creates a slight distance, evoking that ‘once-upon-a-time’ feeling, like a tale passed down through generations.”

London-based Yiddish researcher Izzy Posen translated the script and coached the actors not only to speak Yiddish, but to do so in dialects and speech styles to match their characters’ educations and worldviews. According to Daniel, “the process, though daunting, became something we all loved. It created an immersive, collaborative atmosphere that made the film even more special.”

Seed of Doubt forms part of a cycle of movies from the last ten years that are entirely in Yiddish, or contain Yiddish dialogue, and whose creators have categorized them in the horror genre. The international list is impressive in its scope and diversity, including Demon (2015), The Vigil (2019) and Attachment (2022).

It’s also one of a handful of short films, many of them created by students, which have been making the rounds at film festivals: Shehita (2017), Tzadeikis/Holy Woman (2020) and Striya (2025). What all these movies have in common is that the Yiddish language is significant to the film’s plot, either to mark characters as Jewish or Hasidic, or to represent a mysterious and haunted Jewish past. They invariably contain ambiguous endings that are left open to the viewer to decipher.

Seed of Doubt ends mysteriously with the film’s meaning deliberately left open to interpretation. Daniel notes, “the ambiguity is essential to the unsettling and uncomfortable impact of the ending.” The film contains disturbing scenes, but the unease centers on the profound expressions of human uncertainty and anguish, rather than acts of violence.

A short horror movie acted entirely in Yiddish is a major feat, and making audiences unaware of the effort behind the Yiddish is an even bigger achievement. Seed of Doubt harnesses the Yiddish to tell a story that is both specific to the Eastern European Jewish experience, and universal in its theme of existential dread. It is a film with acting so mesmerizing and visuals so arresting that I forgot partway through that it was in Yiddish.

Seed of Doubt will be playing in New York on March 5 as part of the Havurah Short Short Film Festival.

Rebecca (Rivke) Margolis is a professor at Monash University and the author of The Yiddish Supernatural on Screen: Demons, Dybbuks and Haunted Jewish Pasts.