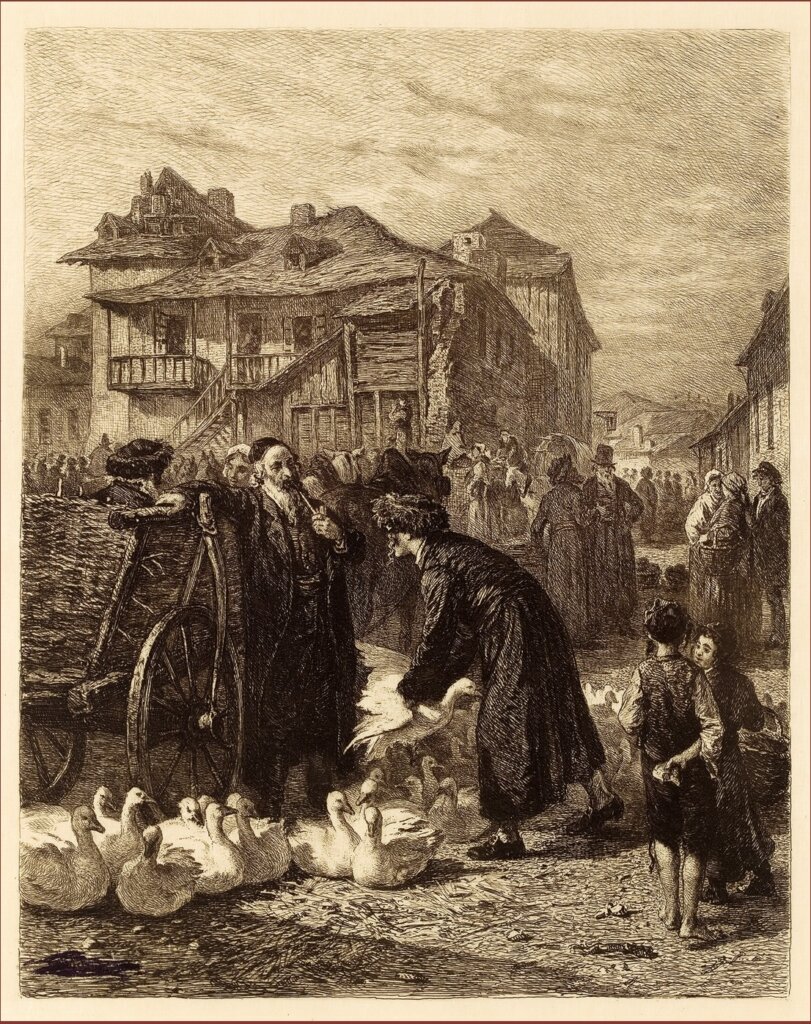

When roast goose was a Hanukkah delicacy, and latkes were fried in its schmaltz

They were slaughtered before Hanukkah in order to render enough fat to last through the winter, when butter was scarce.

Photo by Flickr

As someone who grew up with the tradition of eating potato latkes with smetene, or sour cream, I was completely thrown when I first read Sholem Aleichem’s story “Khanike-gelt,” about the gifts of money traditionally given on Hanukkah.

In the story, a boy in a shtetl describes what the first night of Hanukkah was like at his house. Near the beginning, the father tells his two young sons to go call their mother from the kitchen so that she can hear him bless the Hanukkah candles.

“Mama, quick, time to light the Hanukkah candles!”

“Oy, Hanukkah candles!” Mama exclaimed, tossed aside her utensils (she had slaughtered geese, was frying the goose fat and was making leavened latkes) and hurried into the living room, with Brayne the cook close behind.

I remember wondering: How could she make latkes with goose fat — schmaltz, in Yiddish — when this Hanukkah delicacy is supposed to be eaten with sour cream? After all, there’s no mixing meat and milk in a kosher home.

As it turns out, eating latkes with sour cream wasn’t nearly as popular in the shtetl as having them fried in goose fat. Accounts from the 19th and early 20th centuries report that geese were confined and force-fed during the autumn to fatten them up, Yiddish folklore scholar Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett wrote in this YIVO article.

“They were slaughtered before Hanukkah in order to render enough fat to last through the winter, when butter was scarce. The thick goose skins were rendered with the fat, which was later strained; the cracklings, grivn (or grieven or gribenes), a great delicacy, were stored separately,” Kirshenblatt-Gimblett explained.

Not only were Hanukkah pancakes and fritters fried in goose fat; goose fat was also rendered for Passover at this time and Passover utensils were specially taken out of storage for the purpose.

Some people even made a living selling kosher-for-Passover goose fat, as described in another Sholem Aleichem story, “Gendz” (Geese), a monologue by a woman, Basye, who sells living geese and goose fat. In it, she describes, amid various humorous digressions typical of Sholem Aleichem’s stories, her tough life and the struggles of Jewish women in general.

“Geese famously render lots of schmaltz,” Yiddish food scholar Eve Jochnowitz told me. “Early winter is when they were likely to be slaughtered to provide meat and oil that would serve for the holiday and stay frozen all winter, thanks to the cold.” In fact, she added, a sandwich of goose fat and grated radishes was a beloved snack among the shtetl Jews.

Roasted goose was a traditional holiday entree during the Middle Ages among Jews living in the Rhineland and Eastern Europe, wrote food writer Ronnie Fein. Even the Talmudist Rabbi David Halevi (also known as the “Taz”) noted that goose grivn was a gift given to those who were honored within the community.

In a New York Times article about Hanukkah goose, Gefilteria co-founder Jeffrey Yoskowitz wrote that, on the shabbos of Hanukkah, well-to-d0 Jews would host a feast with roast goose, latkes fried in its schmaltz and most likely pickled vegetables. He quoted the French food writer Édouard de Pomiane, who wrote in 1929 that the goose was a “beneficent animal” for the Jews of Poland as it supplied so much to a household, including feathers for bedding, flesh for roasting and fats for rendering.

And Michael Wex writes in his book Rhapsody in Schmaltz, that the smell of smoking goose fat became the traditional “scent” of Hanukkah.

Ashkenazi Jews who immigrated to the United States often brought the tradition of Hanukkah geese along with them. In her book 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement, Jane Ziegelman said that many 19th century Jewish homemakers raised geese on the Lower East Side, just as they did in the Old Country. But now, they did it in tenement yards and basements, a practice surely disapproved of by sanitary inspectors.

On Hanukkah, she writes, these makeshift goose farms were at their busiest. Restaurants even put up signs reading “Goose liver is here.”

But New York Jewish immigrants weren’t the only ones raising geese. In this home movie, filmed about 1928, shared by Cindra Sereghy-Scull, you can see geese outside her late Aunt Vilma’s home in Cleveland, Ohio.

Chances are, one of those geese was served for Hanukkah dinner that year.