A moving but problematic concert for Holocaust Remembrance Day

An Italian Jewish maestro breathes new life into Yiddish music from the Holocaust, but the composers’ messages got lost in the mix

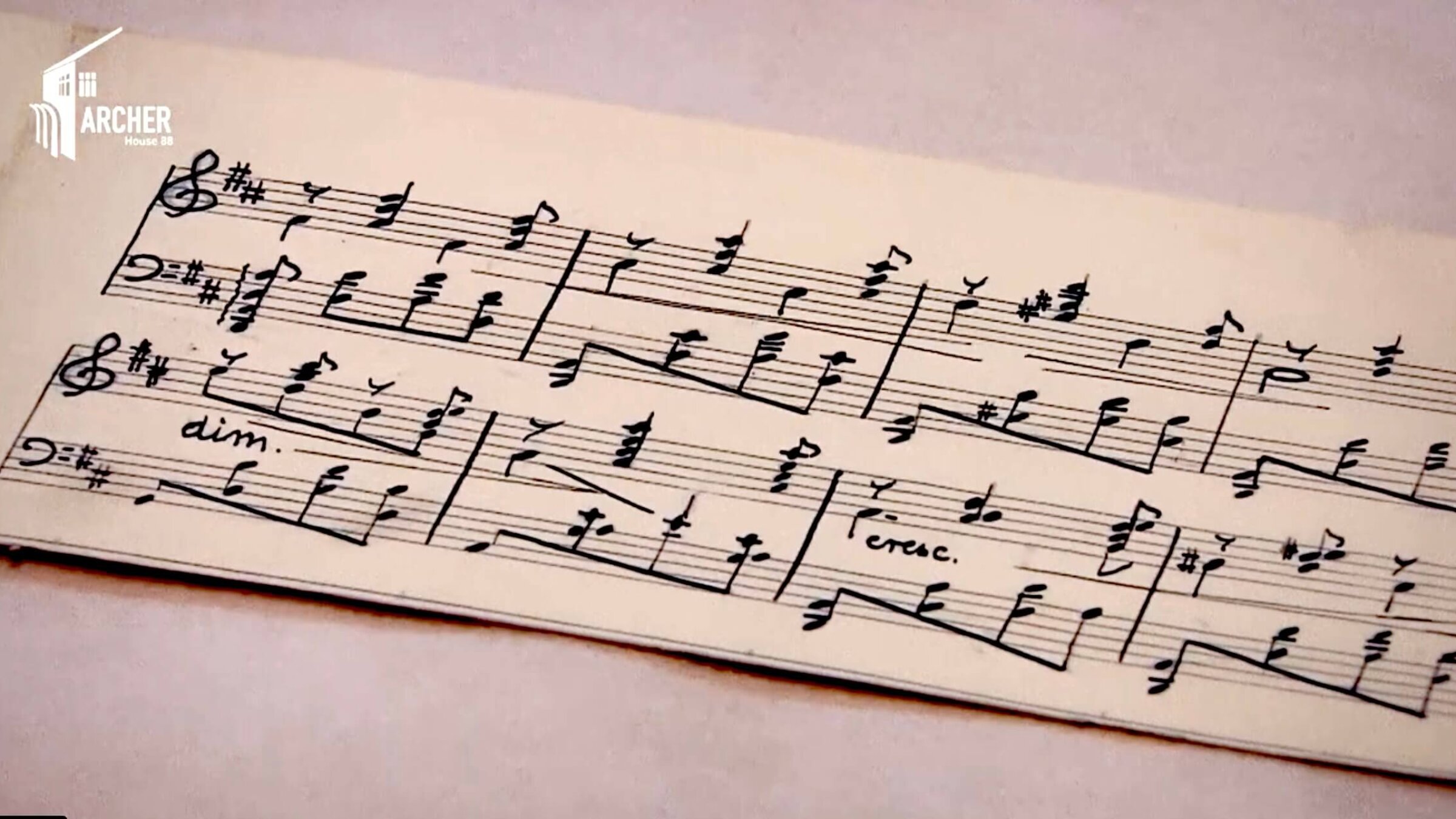

Sheet music of one of the songs performed on Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27, at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. Courtesy of the Kennedy Center

Barletta, a coastal city in Puglia, Italy, is an unexpected place for a massive archive of concentration camp music. Yet one of its citizens, Francesco Lotoro, has spent decades amassing one of the world’s largest collections of this kind.

On Jan. 27, at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., Maestro Lotoro led a concert of this music in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Lotoro’s collection includes not only music from the Nazi camps and ghettoes, but also the camps of the USSR and Hirohito’s Japan, and other sites of mass internment.

Amid a linguistically, tonally and thematically diverse array of works performed, six were Yiddish songs, one of which had its American premiere.

On entering the Kennedy Center, I immediately encountered a rather menacing photo of President Trump, along with those of Vice-President J. D. Vance and their wives. I rushed to the ticket window, got my ticket, passed through security, and approached the Eisenhower Theater.

President Dwight Eisenhower’s bust gazes down upon visitors as they enter. It occurred to me that this was a fitting mekabl ponim (welcome) for a concert of music written by martyrs and survivors of the Holocaust, given then-General Eisenhower’s prescient campaign to film, document and expose the Nazi camps.

I was torn away from this musing by the 10-minute warning chime — a descending arpeggiated major chord (do-sol-mi-do) — and made my way inside.

Five minutes before the advertised start-time (7:30 p.m.), the house was still sparsely seated. Given the political fallout from President Trump’s takeover of the Kennedy Center, I wondered if this concert would be a casualty of the ongoing audience boycott. (Since the concert, the president has announced a two-year closure of the Kennedy Center for renovations.)

At showtime, the house lights were still up, and audience members were still filing in. But when the lights finally dimmed around 7:45, the house was mostly full.

The curtain rose on Lotoro seated at the piano. He performed a wordless lullaby by Polish composer Adam Kopyciński, and without waiting for applause, rose and exited stage right. The co-organizer of the concert, Counter Extremism Project CEO and former U.N. Ambassador under George W. Bush, Mark Wallace, then walked on to give introductory remarks.

The first song of the night was the tragic Yiddish love song “Friling” (“Spring”), composed in the Vilna Ghetto by Avrom Brudno with lyrics by Shmerke Kaczerginski. Written after the death of Kaczerginski’s wife Barbara, “Friling” has been recorded by many artists, including the great Chava Alberstein. Lotoro’s rich but never overpowering orchestration, together with baritone Angelo De Leonardis’s expressive interpretation, were a potent combination.

Like Lotoro’s collection, the concert also featured songs written in other camp systems, in other languages, by other peoples. Lotoro has coined the term “concentrationary music” to encompass music composed in any site of mass internment. Friling was followed by several Polish works, a stunning Roma song, and one English-language serenade by an American POW.

The next Yiddish selection was “Iber Fremde Vegn” (“Across Foreign Roads”), composed around 1942 by Leibu Levin, who was imprisoned in a Soviet camp for 15 years. After an archival recording of Levin singing the song, with Yiddish lyrics projected above the stage, singer Paolo Candido rendered the lyrics in a crystal-clear Yiddish, accompanied by an appropriately restrained orchestration for a more contemplative song of exile.

Candido’s robust voice, together with expert use of gesture, masterfully conveyed the song’s themes and imagery, though no translations were provided for any of the evening’s songs. It was clear to me, at any rate, that the singers understood what they were singing, despite not being Yiddish speakers. (I later confirmed this with Lotoro.)

Then came “Dort In Dem Lager” (“There In the Camp”). I knew two nearly identical versions of this song from 1946 and 1948, but Lotoro worked with a quite different version, recalled half a century later, in 1996.

In my opinion, the 1946 version is the most melodically and lyrically complete, while the one recalled in 1996 collapsed the three verses of the “original” into one. Its rhyme scheme works, but the story it tells has internal inconsistencies. After the concert, I expressed my opinion to Lotoro. “I didn’t use that version at all,” he said of my favored 1946 version. “I completely disregarded it.”

But, as he explained, “I’m not a philologist; I’m a musicologist.” As he put it, the version he chose to arrange and perform “doesn’t cancel the original, philological version.”

Admittedly, the arrangement sung that night by soprano Anna Maria Pansini, accompanied by Lotoro on the piano, is musically the most interesting and complex, because the survivor who recalled it mixed in two lines of a second, unknown song. Lotoro’s spare, intimate arrangement — just piano and voice — counterbalanced the particularly heart-wrenching text and melody. “Sometimes, you have to feel whether a song needs piano or full orchestral accompaniment,” Lotoro told me later in the green room. “It’s important never to exaggerate.”

The song’s most powerful line is its last: Hot shoyn rakhmones, gotenyu. (“Have mercy already, dear God.”) Presumably, few attendees understood the Yiddish, but the anguish expressed in the song was still palpable.

Next came a U.S. premiere: a song from Birkenau titled “In Oyshvitser Flamen” (“In The Flames of Auschwitz”), also sung by Pansini.

The accompaniment was instrumentally richer, but still appropriately understated. One particularly devastating verse translates to:

On holy Motzei Shabbos at night

When we bless the Creator of fire’s lights

Pieces of flesh

Fall from me

Oh, when I

when I recall

How Jews burned

In the flames of Auschwitz.

Closing out the evening was a nearly lost Yiddish song sung by actor and director Jack Garfein, “Tsi Iz Mayn Harts Keyn Harts Fun Keyn Mentshn?” (“Is My Heart the Heart of a Human?”) Archival footage of Garfein singing the song for Lotoro — the only source for the song, because the boy who composed it was killed shortly after Garfein heard him sing it — was shown prior to De Leonardis’ performance. The first two lines translate to:

Is my heart the heart of a human being?

Do I have the right to live, or not?

Garfein’s voice is faint, but the melody is clearly in a minor key, and deeply melancholy. In Lotoro’s interpretation, however, the melody was in a major key, and his orchestration made the song into an expression of hope rather than a lament of its anonymous composer’s dehumanization by the Nazis. The music was beautiful and uplifting, but emotionally dissonant with the words. There are uplifting Yiddish songs from the WWII period, but “Tsi Iz Mayn Harts” isn’t among them.

For an encore, all three singers performed a rousing rendition of “Der Shtrasdenhofer Hymn,” a Yiddish march song from the Strasdenhof forced labor camp. The rather ironic lyrics, however, bitterly complain about the camp, where “one must march and sing.” The singers clapped to the beat, and the audience clapped along too, apparently unaware of how inappropriate it was to do so.

When I asked Lotoro, a Jew by choice, how he works with Yiddish lyrics, he said he’d never had much difficulty with Yiddish due to its similarity to German, but that he’d also had significant help with the Yiddish from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s music curator Bret Werb, and from others. He also shared that the three singers, with whom he’s worked for many years, did philological research of their own, spending significant time working with the Yiddish, Polish and Roma texts before rehearsals. “They don’t get the score two days before, or something like that,” he told me. “I send it to them months in advance.”

Many of the introductory remarks between songs focused on voices being recovered, unsilenced, given new life. But neither lyrics nor song titles were made comprehensible to the largely anglophone American audience. What good is being heard without being understood?

Music may be the universal language, but its vocabulary is small.

Many of the evening’s remarks by non-survivor presenters focused on extremism in the abstract without any mention of far-right nationalism, or of other genocides. An Iranian dissident spoke movingly of the Iranian government’s brutal repression of her people and its sponsorship of anti-Jewish terrorism. A Cuban-American former Republican congresswoman spoke of fleeing a communist dictatorship as a child. Yet not one word was said about China’s ongoing genocide against the Uyghurs of its northwest.

For his part, Maestro Lotoro — a rather self-effacing man — didn’t say a word during the concert. He allowed the music to speak for itself, though much was lost in non-translation.

Lotoro is far from the only collector or interpreter of Holocaust music, and he has been working with “concentrationary” music longer than I have been alive. Besides, much of this precious heritage is widely accessible online. So, if I believe an interpretation misses the mark here or there, someone else can put forth another one more “faithful” to the original material.

“The real goal,” Lotoro told me, “is for all this music to go into circulation around the world.” Thanks to Lotoro’s prolific and artistically top-notch recordings — including a 24-volume album — that seems likely.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that Mark Wallace is the current UN ambassador. He is, in fact, a former UN ambassador who served under George Bush. The current UN ambassador is Mike Waltz.