You Can Teach Everything, Barring a ‘Disaster’

Who Can Name Our Oppression?: Schoolchildren represent the best hope of peace in the region. Image by GETTY IMAGES

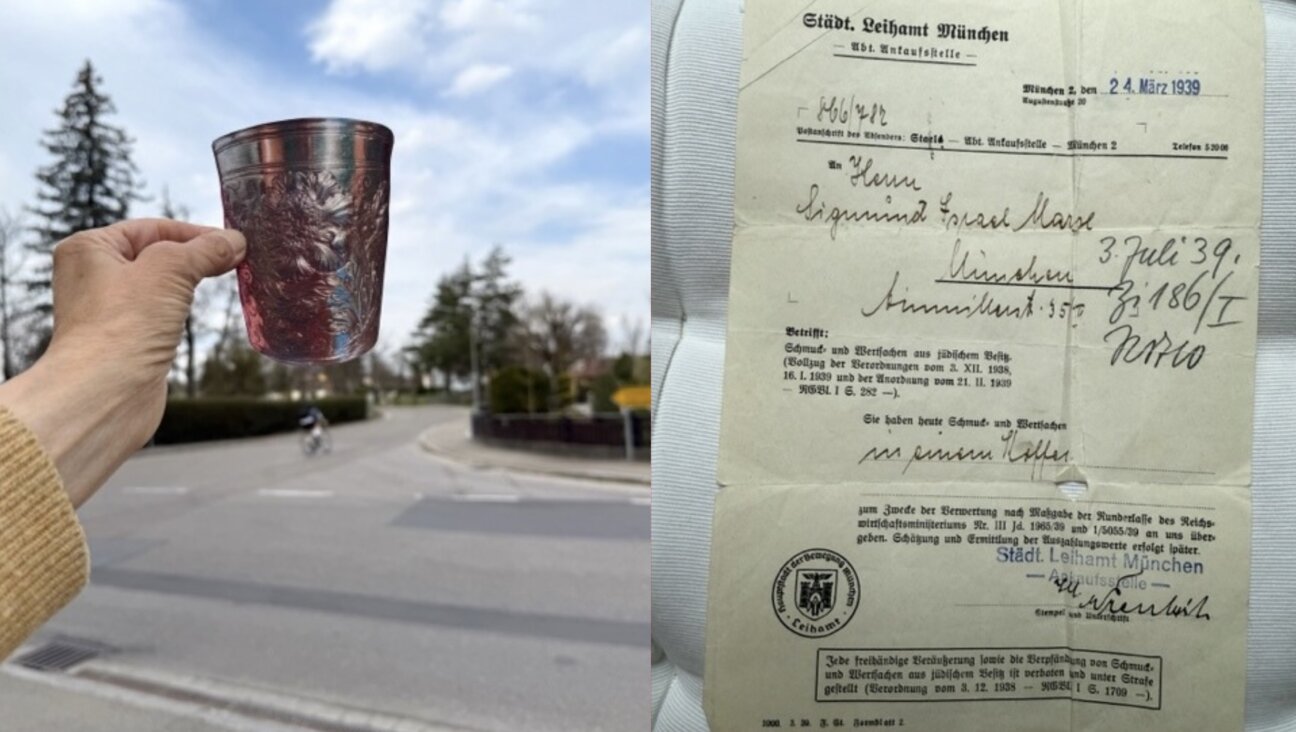

The new school year has begun in Israel, as in much of the world, and with it a renewed debate over the use in Israeli-Arab schoolchildren’s textbooks of the word nakba, or “disaster,” to designate the establishment of Israel in 1948 and the flight from its territory of hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees. Approved for textbook use in 2007 by Labor Party education minister Yuli Tamir after a campaign on its behalf by Israeli-Arab educators, the word — so the current minister, Likud member Gideon Sa’ar, has announced — will be stricken from future editions. Although what the Palestinians experienced in 1948 was “certainly a tragedy” for them, Sa’ar has said, government-okayed books must not refer to the creation of the State of Israel as a tragedy.

Who Can Name Our Oppression?: Schoolchildren represent the best hope of peace in the region. Image by GETTY IMAGES

Recently, “the Nakba” has become, by dint of vigorous Palestinian efforts, such an acknowledged international phrase that it comes as a surprise to learn that it was practically unknown until a little more than 10 years ago.

It derives from the Arabic verb nakaba, “to inflict disaster on someone,” and it was traditionally used in Arabic to refer to any calamity, large or small; as former Israeli-Arab Knesset member Azmi Bishara once observed, it could just as easily have described “the death of a horse or a cow” as a grand historical event. Its first documented use in connection with the events of 1948 was in a book published in the summer of that year by the Syrian-Christian intellectual (and soon-to-be-appointed president of the University of Damascus) Constantine Zureik under the title “Ma’na el-Nakba,” “The Meaning of the Disaster [of Israel’s 1948 victory].”

And yet, Zureik’s book never circulated widely among Palestinians, and nakba as a term for the events of 1948 took decades to enter their political discourse. As the Argentine political scientist Pedro Brieger has pointed out in a Spanish article, “At a conference on Palestine sponsored in Geneva in 1983 by the United Nations, a group of prominent Palestinian intellectuals… [such as] Edward Said, Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Janet Abu-Lughod, Muhammad Hallaj and Elia Zureik spoke about the history of their people without the word Nakba occurring even once.” Nor was the word used by Yasser Arafat when, in 1988, he made the United Nations a forum for declaring Palestinian independence. It was not until 1998, when Arafat instituted an official “Nakba Day” to be held every year on May 15, the anniversary of the declaration of the State of Israel, that the word began to assume the place in Palestinian life that it has now. Its spread since then has been phenomenal. Promoted by countless books, articles, pamphlets, films, conferences, rallies and demonstrations, as well as by the 12 annual Nakba Days that have been subsequently observed, it is well on its way to becoming as universally recognized as the Hebrew word Shoah — to which, as has been remarked, it now leads a kind of parallel shadow existence.

One can, of course, raise an eyebrow at the fact that a word that meant so little to Palestinians not long ago now means so much that its inclusion in their textbooks has become a major issue in Israel. This is not, though, a terribly relevant objection. Words can be politically galvanizing forces, and once introduced, they often galvanize quickly. Think, for example, of the meteoric rise of “gay” in the 1960s and ’70s, or more recently, of the rapid acceptance of “African American.” “Nakba” is a similar case, and it is pointless for partisans of Israel to protest that it is a linguistic Johnny-come-lately.

Still, I think Gideon Sa’ar made the correct decision. Precisely because Nakba is a word with far-reaching political implications, the Israeli educational ministry needs to take these into account. If Nakba Day hadn’t been permanently set for May 15, the matter might look different in Israeli eyes. The Palestinians’ fate has indeed been a tragic one, and Israeli Arabs deserve the right to call it that in their textbooks. But to turn the collective remembrance of this fate into an annual day of mourning for Israel’s establishment is not something that a Jewish state needs to, or should, legitimize. And because the Arabic word nakba is irrevocably associated with Nakba Day, it should not be given Israeli legitimization, either.

This is not a question of censorship. No one is demanding that Israeli Arabs, or anyone else for that matter, stop using the word nakba if they find it appropriate. If Arab teachers in Israel go on employing it in classrooms (as they undoubtedly will), there is nothing that can be done to stop them. Yet, the government that authorizes the textbooks read in these classrooms must make it clear that this is not a usage that is acceptable to it. To do otherwise would be an abdication of its duty.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected].

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 2

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 3

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

- 4

Culture Did this Jewish literary titan have the right idea about Harry Potter and J.K. Rowling after all?

In Case You Missed It

-

Fast Forward Protesters clash in Crown Heights as Ben-Gvir visits Chabad headquarters

-

Yiddish ווידעאָ: היסטאָריקער שמואל קאַסאָוו דערציילט מעשׂיות פֿון זײַן משפּחה־געשיכטעVIDEO: Historian Samuel Kassow shares stories about his family history

דער ווידעאָ איז טשיקאַווע סײַ פֿאַרן אינהאַלט סײַ פֿאַר קאַסאָווס נאַטירלעכן ליטוויש־ייִדיש

-

Culture I have seen the future of America — in a pastrami sandwich in Queens

-

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.