Conservative Rabbis Predict Gay Ban Will Fall, Canadian Shuls Weigh Split With Movement

With leaders of Conservative Judaism predicting an end to the outright ban on gay ordination and same-sex marriage, some of the movement’s more traditional Canadian synagogues are threatening to form a breakaway coalition.

Several movement leaders, speaking at an August 24 meeting in New York, said that the ordination of gay rabbis and the sanctioning of same-sex marriage within Conservative Judaism are near certain. Organized by the movement’s congregational arm, the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the gathering offered a preview of the halachic opinions on homosexuality that are likely to be approved at a December meeting of the movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. A similar meeting was held the previous day in Toronto, with congregations there.

The purpose of the gatherings, said the USCJ’s executive vice president, Rabbi Jerome Epstein, was to help congregations begin to prepare for the “day after” the rulings are handed down.

In December, the law committee “might accept — will accept, I think — two or more of the papers [currently under consideration]: one that affirms the current state of affairs, and one, at least, that liberalizes it,” Epstein told the New York audience. The movement has room enough for congregations differing in their treatment of homosexuality, he said, adding that even if the movement adopts a more liberal position, individual communities will have the final say as to what course to pursue.

Despite such promises of autonomy on the issue, in Canada, where Conservative synagogues tend to be more traditional than their American counterparts, the talk of a more liberal policy is emboldening those who advocate for abandoning the movement’s North American congregational arm altogether.

“The issue of gay ordination will certainly exacerbate the situation for us here in Canada and may indeed be the straw that pushes us into this declaration of independence,” said Rabbi Steven Saltzman, who presides over Toronto’s Adath Israel Congregation. “The movement in the U.S. has moved so far to the left on issues of tradition that we find it difficult to fall in step behind it.”

The possibility of a Canadian split from the USCJ first surfaced last year over the equally contentious matter of egalitarian services. At the USCJ’s 2005 biennial convention in Boston, an American rabbi prompted an outcry from his peers to the north when he suggested that allowing nonegalitarian congregations — those that restrict women’s participation — in the movement was immoral and misogynistic. Only a handful of the 19 Conservative synagogues in Canada are egalitarian.

The controversy ignited discussions among rabbis and lay leaders in Toronto and Montreal to consider whether they might forge a separate Canadian synagogue group while maintaining ties to the Conservative movement in America.

Saltzman, who has led the charge to break away from the USCJ, contends that the creation of a distinctly Canadian group would not be an all-out rejection of the Conservative movement. He cites as examples Israel and South America, where there are independent groups that still play a role with the Conservative movement internationally.

Some Conservative leaders in Canada downplayed the possibility of a split.

According to Paul Kochberg, president of the USCJ’s Canadian region, previous discussions surrounding the possibility of creating a distinct Canadian union already have faltered. Kochberg, who is also chairman of the USCJ’s council of regional presidents, said that he would oppose any plan to disengage from the central North American body, and that he saw it as an unlikely possibility for the future.

“The real concern about the liberal direction of the Conservative movement is centered around a few synagogues in Toronto,” said Kochberg, referring in part to Saltzman’s congregation. “And because I don’t believe the sentiment is widespread beyond those couple synagogues in Toronto, I don’t think there’s a great deal of support for the notion” of a breakaway organization.

At the recent USCJ meeting in New York, Epstein acknowledged that while he believed that the movement had room enough for congregations differing in their treatment of homosexuality, the question of whether or not to accept gay rabbis and gay marriage “could be, at least theoretically, divisive” within synagogues.

In an interview with the Forward, Epstein expressed concern over the possibility of losing the Canadian region. “I’d be foolish to tell you that this doesn’t affect us,” he said, adding that “we want to keep those congregations in.”

Epstein said it is important that “rightwing congregations feel comfortable” in the movement. “We have a lot of things we identify with together, we share a lot of common goals, and it’s important for us try as much as possible to work with them.” And that, he added, includes engaging in dialogue and displaying sensitivity to different views, as was done at the meetings in Toronto and New York.

For several years, the Rabbinical Assembly’s law committee has been actively reconsidering the movement’s historical ban on homosexuality, which was affirmed as recently as 1992 and stems from a passage in Leviticus stating, “Do not lie with a man as one lies with a woman; it is an abomination.” This past March, four opinions — two on either side of the issue — were submitted to the committee for review, with the final vote scheduled for December.

Since that time, Conservative Judaism has ushered in another dramatic change: In April, the movement’s flagship institution, the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, announced that its retiring longtime chancellor, Rabbi Ismar Schorsch, would be succeeded by Arnold Eisen, a Stanford University professor who is not a rabbi. While Schorsch had been an unflagging opponent of lifting the ban on homosexuality and had long argued that such a move could split the movement, Eisen quickly voiced his support for allowing gays and lesbians into the rabbinate. Rabbi Bradley Arston, dean of the Conservative movement’s rabbinical school at the University of Judaism in Los Angeles, has said in the past that he would admit gay rabbinical students if the ban is lifted. The rector of U.J.’s rabbinical seminary, Rabbi Elliot Dorff, is a law committee member and a co-author of the liberal opinion that is expected to pass.

On August 24, at Congregation Shaare Zedek on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, the panelists included Dorff and Rabbi Joel Roth, a fellow law committee member and a professor at JTS. Dorff’s opinion — co-authored with rabbis Daniel Nevins and Avram Reisner — would permit gay ordination and marriage, as well as some homosexual acts, while maintaining a ban on anal sex. Roth’s opinion, which is largely a restatement of his approved 1992 opinion, would uphold the ban on homosexuality. Throughout the evening, the speakers repeatedly expressed certainty that both would pass.

“I think it’s a foregone conclusion” that there will be two decisions passed, Roth told the Forward after the event. “The only question is whether there will be two or three passed,” he added in reference to another liberal decision, co-authored by Rabbi Gordon Tucker of Temple Israel Center in White Plains, N.Y., that would lift all restrictions on homosexual behavior.

Controversy over procedural issues has dogged the law committee since its March meeting, when a majority of members voted to designate Tucker’s opinion as a takanah, or amendment to biblical law, rather than as a teshuvah, or interpretation. The distinction proved important because while under movement rules a teshuvah only requires the votes of six of the 25 voting members on the law committee to be considered an acceptable interpretation, in June 2005 the R.A.’s executive committee adopted a rule stipulating that a decision designated as a takanah would require 20 votes to pass. Previously there had not been different thresholds for the two kinds of decisions, and the author of an opinion had discretion over that opinion’s designation.

Although members of the R.A. voted to lower the threshold for passing takanot to 13 votes at their convention in late March, the prospects for Tucker’s opinion remain murky. In an e-mail to the Forward, Tucker said that he was removing his name from the opinion that he co-authored, which is being considered with several other liberal papers.

“Since the Committee has, in effect, acquiesced in the Rabbinical Assembly Executive Council decision to allow a majority of the Committee to declare a Teshuvah to be a Takanah, over the objection of the author of the Teshuvah, I am unwilling to grant legitimacy to this process, even implicitly,” Tucker wrote. “What has happened,” he continued, “is a serious reversal of 79 years of Law Committee practice, which will have all sorts of negative, and unintended (I assume) consequences. In effect, no position held by a minority of the Law Committee on any sufficiently contentious issue can any longer gain legitimacy in the Movement, since a bare majority of the Committee can quash it by voting to declare it to be a Takanah. I will not participate in the process as an author under these circumstances (though I will participate as a voting member in the deliberations).”

While the discussion in March had suggested that some law committee members believed that Dorff’s opinion also might be in danger of being designated as a takanah, Dorff told the Forward that he viewed that possibility as highly unlikely.

In an interview with the Forward after the meeting, Epstein said that the USCJ is planning additional meetings on homosexuality in other cities this fall, and is currently exploring other ways of helping congregations deal with the likely decisions.

At the meeting in New York, both Epstein and Dorff affirmed a commonly held view among Conservative leaders that the movement is a “big tent” that proudly tolerates a multiplicity of opinions on such difficult questions as the role of women and the permissibility of gay relationships. Roth, however, said he viewed the movement as being more like a “bell curve” than like an “umbrella,” and worried that as the curve moves to the left on social issues, those who do not favor liberalization feel increasingly rejected.

“At this time, the University of Judaism has no nonegalitarian minyan and JTS does with some difficulty,” Roth told the audience, adding that, in his view, JTS students who do not believe that women should count in a minyan or be called to the Torah “are reviled and castigated by their peers as moral misogynists.”

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Culture Trump wants to honor Hannah Arendt in a ‘Garden of American Heroes.’ Is this a joke?

- 2

Opinion The dangerous Nazi legend behind Trump’s ruthless grab for power

- 3

Fast Forward The invitation said, ‘No Jews.’ The response from campus officials, at least, was real.

- 4

Opinion A Holocaust perpetrator was just celebrated on US soil. I think I know why no one objected.

In Case You Missed It

-

Film & TV In ‘The Rehearsal,’ Nathan Fielder fights the removal of his Holocaust fashion episode

-

Fast Forward AJC, USC Shoah Foundation announce partnership to document antisemitism since World War II

-

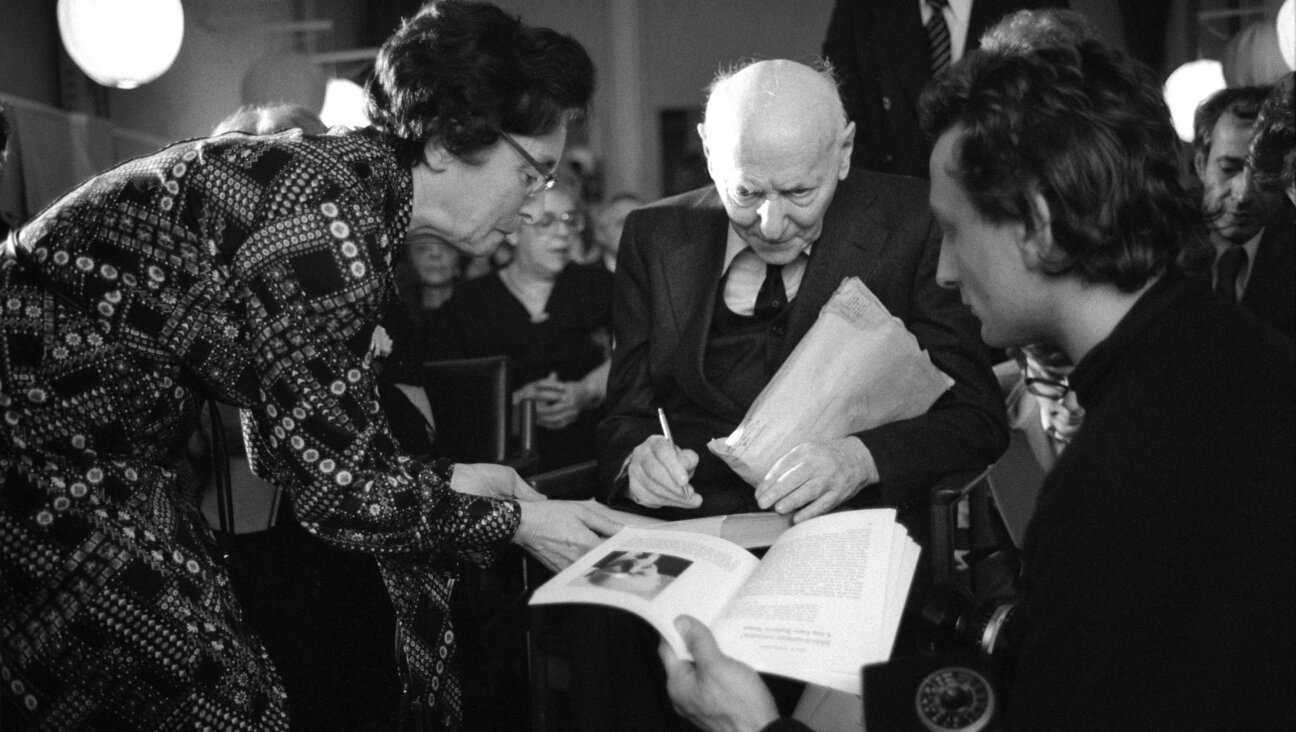

Yiddish יצחק באַשעװיסעס מיינונגען וועגן די אַמעריקאַנער ייִדןIsaac Bashevis’ opinion of American Jews

אין זײַנע „פֿאָרווערטס“־אַרטיקלען האָט ער קריטיקירט זייער צוגאַנג צום חורבן און צו ייִדישקײט.

-

Culture In a Haredi Jerusalem neighborhood, doctors’ visits are free, but the wait may cost you

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.