The Specter of Xenophobia Stalks Europe

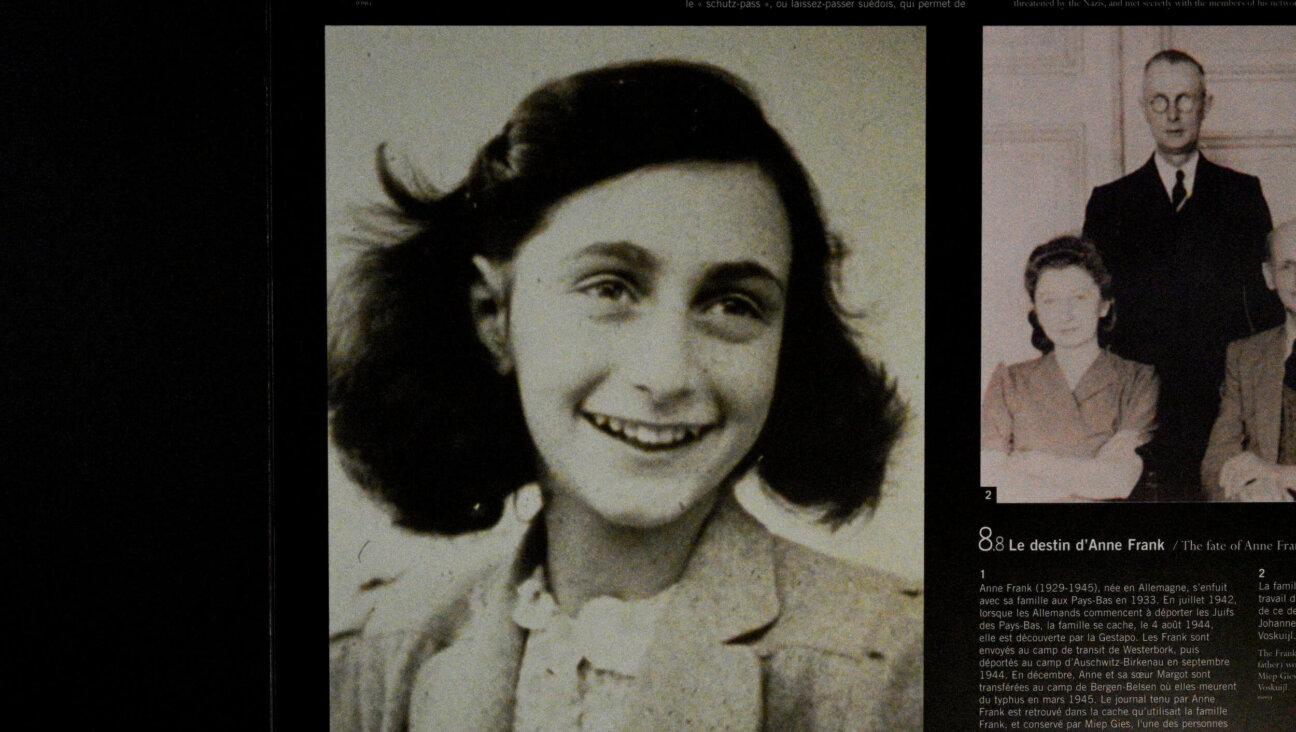

Immigration Instigation: European politicians have tried to link Muslim immigrants to terrorism while ignoring their own xenophobia. Image by getty images

Poetry, Robert Frost famously said, is what gets lost in translation. But as “L’Allemagne Disparaît,” the newly issued French translation of Thilo Sarrazin’s “Deutschland Schafft Sich Ab,” reminds us, demagoguery survives translation all too well.

While the translation of the French title, “Germany Is Disappearing,” transforms that of the German title, “Germany Does Itself In,” from the active to the passive, the author’s bleakly Spenglerian warning remains constant. No less constant, unhappily, is Sarrazin’s habit of playing fast and loose with statistics and with the plying of combustible claims. His argument that Germany will be dumbed down by the cultural practices and, yes, genetic inferiority of its large Turkish community sounds no better, and makes no more sense, in French than it did in German.

Against a flaming red background, the cover of the French edition trumpets: “With two million copies sold, the book that convulsed Germany.” This is one claim that is beyond dispute. When “Deutschland Schafft Sich Ab” appeared in 2010, the effect was seismic. While the publisher, Verlags-Anstalt, frantically churned out copies to meet popular demand, politicians on the right and left scrambled no less frantically, in search of a response to the extraordinary public reaction. The Christian Democrats feared that Sarrazin, a Social Democrat who had served as an economist in a number of administrative positions before joining the central board of the Bundesbank, had handed them a poisoned chalice, while the Social Democrats couldn’t decide if they should ignore or attack their colleague. The only decisive response came from the Bundesbank, which promptly dismissed him.

But Sarrazin no longer needs to punch the clock: He has become a wildly successful writer. While his success was unexpected, it is not at all accidental: Book sales had already been sparked by a number of incendiary assertions. Most startling, perhaps, was his attempt to explain the scientific, artistic and professional predominance of Jews to a specific “Jewish gene.” Though Sarrazin seemed surprised by the outrage — after all, wasn’t this a compliment, not a criticism, of Jews? — he eventually apologized and retracted the claim.

Yet, as Sander Gilman, a renowned historian of German culture and literature, observed recently, the recycling of 19th-century racial theories in regard to the Jews is just the opening gambit in Sarrazin’s book. Sarrazin’s clumsy philo-Semitic gesture serves as both cover and justification for his phobia toward the 4 million men, women and children who constitute Germany’s Muslim, and in particular its Turkish, population. This community, in Sarrazin’s telling, holds Germany’s future hostage. Turks presently represent about 5% of the German population and, Sarrazin argues, will soon outstrip the declining “German” population. Moreover, the lowest rung is home to those with the lowest intelligence — and since intelligence, as Sarrazin claims, is hereditary… well, only a Turk would need to have that spelled out.

The French can now imbibe “en version Française” this same “very, very bad science,” as Gilman put it. Since the book has been translated into French — no English edition has, for now, been announced — Sarrazin is allowed, in televised interviews, to fob off on a new audience the claim to scientific soundness (a claim, moreover, that went uncontested by the newscaster on the Gallic equivalent of CNN, France 24).

More disturbingly, the translation’s appearance reflects that similar fears simmer on both sides of the Rhine. In his concluding chapter, Sarrazin writes that the rise of sea levels worries him less than the decline of Germany’s cultural legacy (and genetic makeup, one assumes) — a fear, he continues, that also haunts Germany’s European neighbors, including the French.

Clearly, a specter haunts Europe — and it isn’t the hammer and sickle of communism. But neither is it the crescent and star of Islam. Instead, it is the feverish specter spawned in the European imagination by brutal but isolated acts of Islamist extremism. Earlier this year, a poll taken by Le Monde revealed that an astonishing 74% of French citizens agreed that Islam was an “intolerant” religion incompatible with republican values. This more or less mirrors, according to the mass daily Bild Am Sonntag, the percentage of Germans who agree with Sarrazin’s view of their fellow Turks. And while there is no German equivalent to France’s xenophobic National Front, which won nearly 20% of the vote in last year’s presidential election, German polls revealed that nearly 20% of respondents would vote for a political movement led by Sarrazin.

The traditional political parties in both Germany and France have largely failed to respond to this growing unease. Or, more accurately, they have responded either demagogically, confusedly or both. During last year’s presidential election, Nicolas Sarkozy attempted to chip away at the National Front electorate by playing the immigrant card. His successor as head of the neo-Gaullist Union for a Popular Movement, Jean-François Copé, has adopted his anti-Muslim playbook (and, more recently, extended it to homosexuals). At the same time, the Socialists under François Hollande have been, in political commentator Serge Federbusch’s phrase, “enfumer” or blowing smoke to disguise their confusion. Thus, at the very same moment the government announces its plans to improve the situation of the Roma, the public learns that the police have demolished yet another Roma camp.

The political situation in Germany is no less confused. The Socialists, which first sought to expel Sarrazin from the party, were checked by the popular outcry on the economist’s behalf. As for the Christian Democrats, while Angela Merkel publicly expressed her disgust with Sarrazin’s racialist claims, other party members acknowledged that a chasm divided the political elite from most Germans. In a carefully phrased sentence, one regional leader, Peter Hauk, declared: “While I do not share some of Sarrazin’s views, he does address issues that our citizens are concerned about.”

This is the heart of the political problem in both countries: Mainstream parties must acknowledge the legitimate economic and social concerns of their electorates without pandering to their prejudices or playing on their fears. Inevitably, there are German Turks and French Muslims who reject the secular and republican values of their nations. But they are the few: The great majority of Muslims on both sides of the Rhine have shown their commitment to these very same values. The danger comes not just from the few Muslim extremists, but also from those who pretend to defend the nation against them.

Robert Zaretsky is a professor of history at The Honors College at the University of Houston and is the author of the forthcoming “A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning” (Harvard University Press).