Onward and Upward with Matisyahu in Krakow

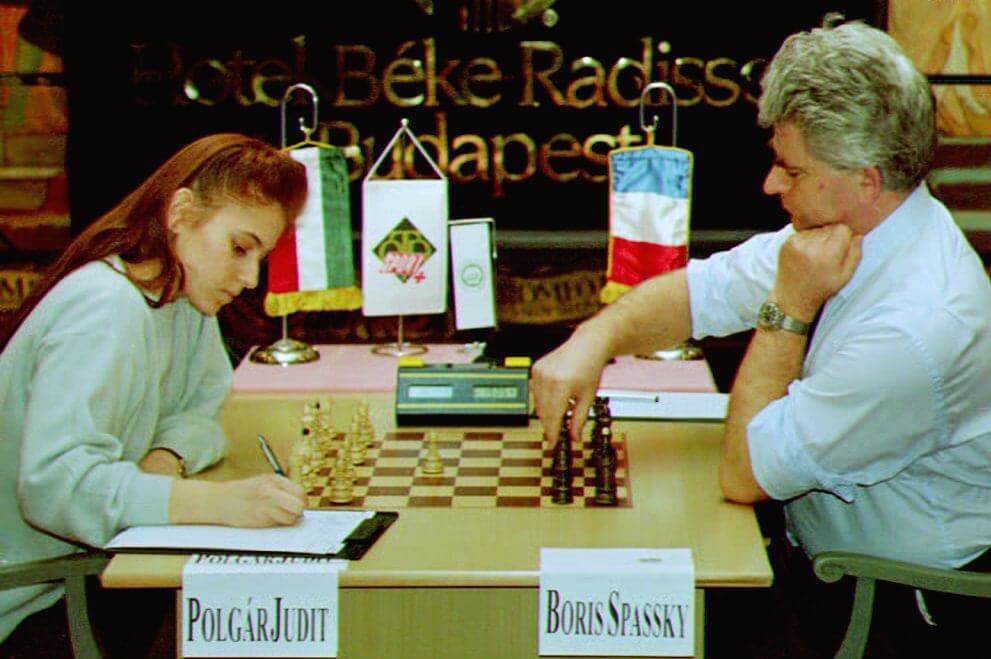

Poland?s New Tune: Matisyahu, seen here before he shed his Hasidic garb, attended this year?s Jewish Culture Festival in Krakow. Image by Getty Images

In the sultry darkness of a summer night, a tall, skinny figure with close-cropped hair and a purple T-shirt threaded through a beer garden during Krakow’s Jewish Culture Festival, the annual nine-day extravaganza of performance, exhibition, debate and intensive interaction that for a quarter of a century now has been a catalyst of Krakow’s Jewish cultural revival.

Bridging the open space between the city’s lively Jewish community center, which hosted dozens of festival events, and the grandiose Tempel Synagogue, venue for many of the concerts, the garden served as an informal salon where public and performers, Jews and non-Jews alike, could shmooze.

Whispers trailed in the newcomer’s wake: “Matisyahu’s here!”

The American singer, much less recognizable since he shed his Hasidic garb, blended with the dozens of other folks sipping their drinks as he made his way through the slatted wooden tables and sat down with a group that included Jonathan Ornstein, director of Krakow’s Jewish community center, and Janusz Makuch, the bearded, non-Jewish Pole who co-founded the festival in 1988 and is still both its director and its main driving force.

Matisyahu wasn’t on the program, though he has performed here in the past.

This time, en route to a gig in northern Poland, he had simply dropped in to hang with the festival crowd in Kazimierz, Krakow’s historic Jewish district.

Over the past two decades, Kazimierz has famously been transformed from a rundown slum, the quintessential Jewish graveyard, into a major tourist attraction: a burgeoning hub of revitalized Jewish culture, life, consciousness and commercial kitsch — as well as the city’s liveliest center of clubs, pubs and other late-night venues.

“We must have been out till 5 in the morning,” Ornstein told me the next day.

I’ve been writing about Kazimierz since 1990 and about the festival itself for nearly that long, returning each summer, at least for a few festival days, to monitor changes in the place, the program and the issues that swirl around both of them.

To me, Matisyahu’s under-the-radar appearance brought home one of the most striking of these changes. Clearly for him — and for the hundreds, maybe thousands, of other Jewish tourists who now flock here — the long post-Holocaust taboo on visiting Poland for pleasure has been broken.

This is no mean feat and has taken years to come about. Auschwitz is just an hour’s drive from Krakow, and the new attitude is by no means universal. But I heard it echoed clearly by a Canadian woman staying in my hotel.

“There’s no downside to Krakow,” the woman told me over breakfast. “As for the festival, it’s great. I’m doing as many activities as I can, and I’m already planning to come back with friends in two years.”

One of the factors in this change has been the increasingly high profile of the JCC, which opened five years ago as a neutral Jewish space accessible to all streams and forms of Jewishness and Jewish expression, normative or not.

Now one of the hubs of the festival, the JCC is, importantly, recognized as a “Jewish” Jewish space, in contrast to most of the city’s other Jewish-oriented venues and institutions. Its involvement has changed radically the dynamics of an event that long was viewed as a Jewish festival produced by non-Jews for a non-Jewish audience. Non-Jewish Poles still make up the vast majority of the festival’s attendees.

Among the JCC’s annual festival offerings is a kosher Sabbath dinner. This year, hosted in the 17th-century Izaak Synagogue, the dinner drew nearly 400 people.

“Visitors to Krakow now understand that they are not coming to a museum, but rather to a place with a small but increasingly active Jewish community,” Ornstein told me. “Understanding that fact puts the festival in a different context from a Jewish point of view. It is not only connecting Poles to Jewish culture, but helping create an environment in which the local Jewish community feels welcome and can thrive. This festival can make a claim that few others can: It is helping to rebuild a Jewish community long thought by many to be without a future.”

This year, the concepts of “Jewish” and “Jewishness” — and the ways they are defined, perceived, described and enacted — formed one of the main themes confronted in the many festival lectures, workshops and discussions.

I took part in a public conversation at the JCC, called “Jewish. Jewish? ‘Jewish’ Jewish!” It addressed shifting definitions, particularly in Kazimierz, where the transformations have created a complex of new Jewish authenticities that are quite different from the Krakow Jewish world that was destroyed in the Holocaust but are still real components of today’s living city.

After all, few if any of the young Poles and visitors who now throng the district’s many new cafes or volunteer at the JCC have any direct memories of Kazimierz before the festival began drawing crowds, when no modern Jewish museums and culture centers offered their programs, and no Jewish (or Jewish-style) commercial venues plied their trade.

“The resonance of the festival has become larger than the festival itself. And maybe this is the important thing,” the noted Yiddish singer Michael Alpert commented backstage during the festival’s traditional marathon open-air final concert on Kazimierz’s main square, Szeroka Street. “There’s ‘normalization,’” Alpert said, “and if it’s normal, it’s not as exotic.”

Nonetheless, he said, the festival’s main museum exhibition demonstrated an unsettling deep-seated sense of the “weird” that still surrounds Jewish issues.

This provocative show confronted the perception of what is understood as Jewish or “Jewish.” Titled “Souvenir, Talisman, Toy” and curated by Concordia University anthropologist Erica Lehrer, it explored the history, meaning and symbolism of the ubiquitous carved wooden figurines of Jews, frequently seen at Polish souvenir stalls and which often perpetuate sometimes toxic stereotypes.

The exhibit placed these figures in the context of both folk art and folk fantasy. In doing so, particularly against the pervasive good vibes of the festival, it served to highlight — and confront — the contradictory ways that “Jews” and “Jewishness” are perceived and represented in contemporary Poland.

One particular focus was on the myriad “Jewish” figures that clutch money and are used as “good luck” charms said to bring purchasers prosperity. Some observers actually view such “penny Jews” as embodying “positive” stereotypes, without ill intention. In exhibition video interviews, vendors and purchasers alike spoke openly about the magical properties of such figures, some of which are so abstract that, though bought, sold and recognized as “Jews,” they look more like aliens than human beings.

“As a Jewish dancer, people look at my physicality as a Jew,” said Steve Weintraub, the festival’s Jewish dance teacher, with whom I visited the exhibit. “What does this mean about how people are seeing me?”

That, of course, was the question. Or one of the questions. Only days after the festival’s conclusion, the lower house of Poland’s parliament voted down a bill that would have allowed Jewish (and Muslim) ritual animal slaughter.

It’s not for nothing that the exhibition advertisement featured the grotesque head of a wooden Jew, all staring eyes, fur hat and flaring peyes, or sidelocks. From posters and banners it glared proudly — even defiantly — out at the manifold new realities of Jewish Kazimierz with an expression of amazement, inquiry and possibly apprehension.

Ruth Ellen Gruber writes frequently on Jewish issues. Her books include “Virtually Jewish: Reinventing Jewish Culture in Europe” (University of California Press).