The Greatest Yiddish Writer You Never Heard Of

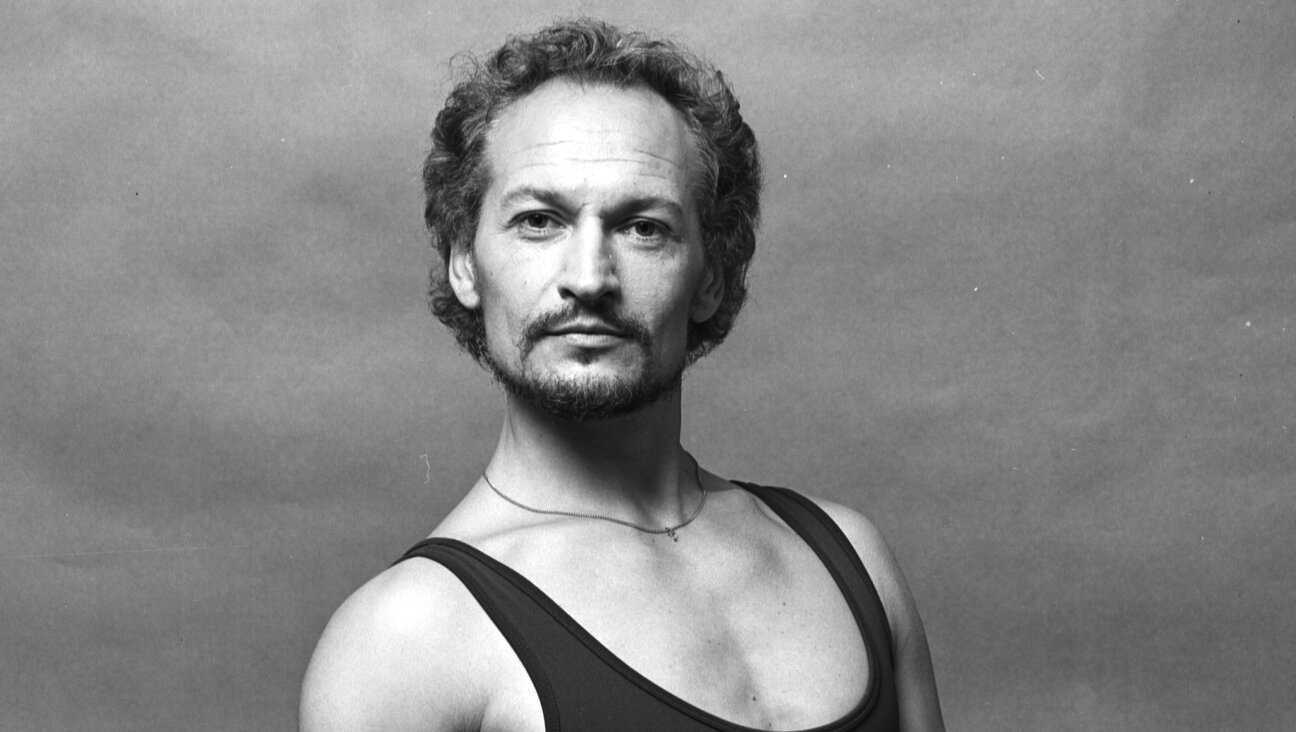

19th Century Man: For Dinezon, the changes engulfing Eastern European Jewry in the late 19th century signaled neither progress nor destruction. Image by Jewish Storyteller Press

● Memories and Scenes: Shtetl, Childhood, Writers

By Jacob Dinezon Translated from the Yiddish by Tina Lunson

Jewish Storyteller Press, 240 pages, $19.95

In “Apocalypse,” a short story by Yiddish writer Jacob Dinezon, three elderly Jews get to talking about the concept of Rothschild, and about whether such a person actually exists. “In reality there really is no Rothschild,” Meshulem the Teacher claims. “It is just an exaggeration, an illustration of great riches.”

Eventually the men decide that there is a real Rothschild. But if he does exist, why hasn’t he visited their master, the Rebbe of Vinogrodke? Obviously, Rothschild must not know about the rebbe. If he did, the combination of the rebbe’s wisdom and Rothschild’s wealth would surely bring the Messiah. So Meshulem decides he will go and tell Rothschild about the rebbe.

The story, which is included in “Memories and Scenes: Shtetl, Childhood, Writers,” a recently translated collection of Dinezon’s stories, could be taken as an enlightenment critique of Hasidic Judaism, a common trope of the time. The Rebbe of Vinogrodke is corrupt — when Meshulem comes for a blessing, he is thrown out because he can’t make a donation — and his followers are ignorant. Meshulem’s fanatical piety is self-destructive, leading him to a life of impoverished wandering. Religion here is the source of superstition, error and personal destruction.

But the piece doesn’t come across that way. Instead, “Apocalypse” is a sympathetic homage to the simple Jews who spend their lives gossiping in synagogue, and for Meshulem, whose mission turns into a symbolic quest.

His long journey opened his eyes, and he saw that the Redemption did not depend on a Vinogrodke Rebbe or on a Rothschild. The real Redemption depends on the real deliverer — the true Jew — who will bring the Redemption without miracles from rebbes or fortunes from Rothschilds…

If only he could be sure that the one he sought was really out there and that if you seek, you will find him.

Like Meshulem, Dinezon was a champion of the little people. For him, the changes engulfing Eastern European Jewry in the late 19th century signaled neither progress, as they did for proponents of Haskalah, Jewish enlightenment; nor destruction, as they did for the traditional rabbinic establishment. Instead they meant a tragic but inevitable loss of innocence, which became his great theme. Unlike other writers, who used the innocent as a figure of fun — the schlemiels of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Chelm stories, for example — Dinezon’s characters are invested with rare pathos.

Dinezon experienced his own share of tragedy. Born in New Zager, Lithuania, in the early 1850s (the exact year is uncertain), he was orphaned around age 12 and went to live with an uncle in Mohilev. As a teenager he studied modern subjects like math, science and European literature and, like his contemporary Sholem Aleichem, became the live-in tutor for a wealthy family. Unlike Sholem Aleichem, however, who married his student and inherited his father-in-law’s wealth, Dinezon’s pupil married someone else, and Dinezon suffered the indignity of having to facilitate the match.

Dinezon remained a bachelor for the rest of his life, a circumstance that contributed to his reputation as the “uncle” of Yiddish literature, or the “mother,” as his biographer, Shmuel Rozshanski, put it. Describing Dinezon in his own inimitable style, Sholem Aleichem wrote:

There is somewhere in the city of Warsaw, a tiny, spare, graying, little man with tiny but spotlessly clean little hands, with a little graying beard — it once was reddish — and with kindly eyes forever smiling, even when moist with tears…. He smokes little cigarettes rolled with his own little fingers; he drinks his own tea, made in his own little teapot…. And this good uncle is called Uncle Dinezon.

One suspects that if Dinezon didn’t exist, Sholem Aleichem would have had to invent him.

Today, Dinezon is not nearly as well known as Sholem Aleichem or I.L. Peretz, who was his longtime friend and colleague in Warsaw. This is partly because Dinezon was less prolific than these other writers, and partly because his work didn’t always rise to the same level. A few of his early novels were sentimental potboilers, and despite their popularity, he came to regret their influence on later writers.

The present volume, deftly translated by Tina Lunson with an introduction by publisher and editor Scott Hilton Davis, is itself an uneven, hybrid work. First published in 1928, nearly 10 years after Dinezon’s death, it includes character sketches and short stories, as well as autobiographical and essayistic pieces on subjects like the Dreyfus Affair and Yiddish theater. But despite a few weak spots, most of the stories are excellent, and a few are genuine masterpieces.

The strongest story in the collection — and indeed, one of the best short stories I’ve ever read — is “Borekh,” a piece that exemplifies Dinezon’s sympathy for marginal figures. The title character is a mentally disabled orphan who lives in the study house of a small Jewish town. He spends his days helping the townspeople with their tasks and playing with their children, for whom he carves intricate wooden toys. Though he is unable to study Talmud, he idealizes his fellow students, especially the precocious “Brisker,” who is said to be a genius.

One day, however, while serving guests at a wedding, Borekh’s simple existence comes suddenly undone. “Borekh, tell me, how old are you?” Bunim the Matchmaker asks him. Borekh doesn’t know the answer, but the prospect of adulthood torments him. “The question of his age dug at his mind like a plow,” Dinezon writes.

In that moment he was angry at God, who had created the world in such a way that living people must get older from year to year. ‘How would it bother God if we were children our whole lives? Or at least to remain happy as children?’

Eventually Borekh realizes that he can no longer continue the life he has been living, and must strike out to make a new life elsewhere.

As with many of Dinezon’s characters, Borekh’s fate can be read as symbolic of that of Eastern European Jewry as a whole. In these pieces, Dinezon presents an Old World setting populated by a quaint cast of characters, while calling their very existence into question. In the first story in the volume, “Memories,” he evokes this fragility through metaphor, comparing a pious character’s prayers to “a noise like a bomb falling or a marching army,” and “the salute of a hundred canons firing at once.” Even before World War I, military imagery didn’t bode well for the stability of Jewish life.

Yet Dinezon’s work is primarily about individuals, whatever its historical resonances. In “Memories and Scenes,” characters include the brazen tailor Sholem Yoyne, whose whiskey gives him the courage to speak out against community leaders; the golden-voiced Motl Farber, who isn’t allowed to lead prayers on the High Holidays because he’s merely a house painter, and the obsessed tutor Yosl Algebrenik, whose own wife prefers him to be poor because otherwise “he would probably pay people to come learn algebra from him.” In the case of “Borekh,” Dinezon convincingly represents the interiority of a mentally challenged character, something few fiction writers have ever successfully done.

Like the best Yiddish literature of its time, Dinezon’s writing walks the line between sympathy and sentimentality, and lands safely on the right side. Rather than romanticize his subjects, Dinezon humanizes them. It’s unlikely that Dinezon will now attain the same renown as Sholem Aleichem or Peretz, but this collection belongs on the shelf next to theirs. It’s rare to find a real masterpiece, never mind one written more than 100 years ago and only now available in English. “Memories and Scenes” is one of those happy occasions.

Ezra Glinter is the deputy arts editor of the Forward. Contact him at [email protected] or on Twitter, @EzraG.