Did Illinois Bungle First-in-Nation Anti-BDS Blacklist?

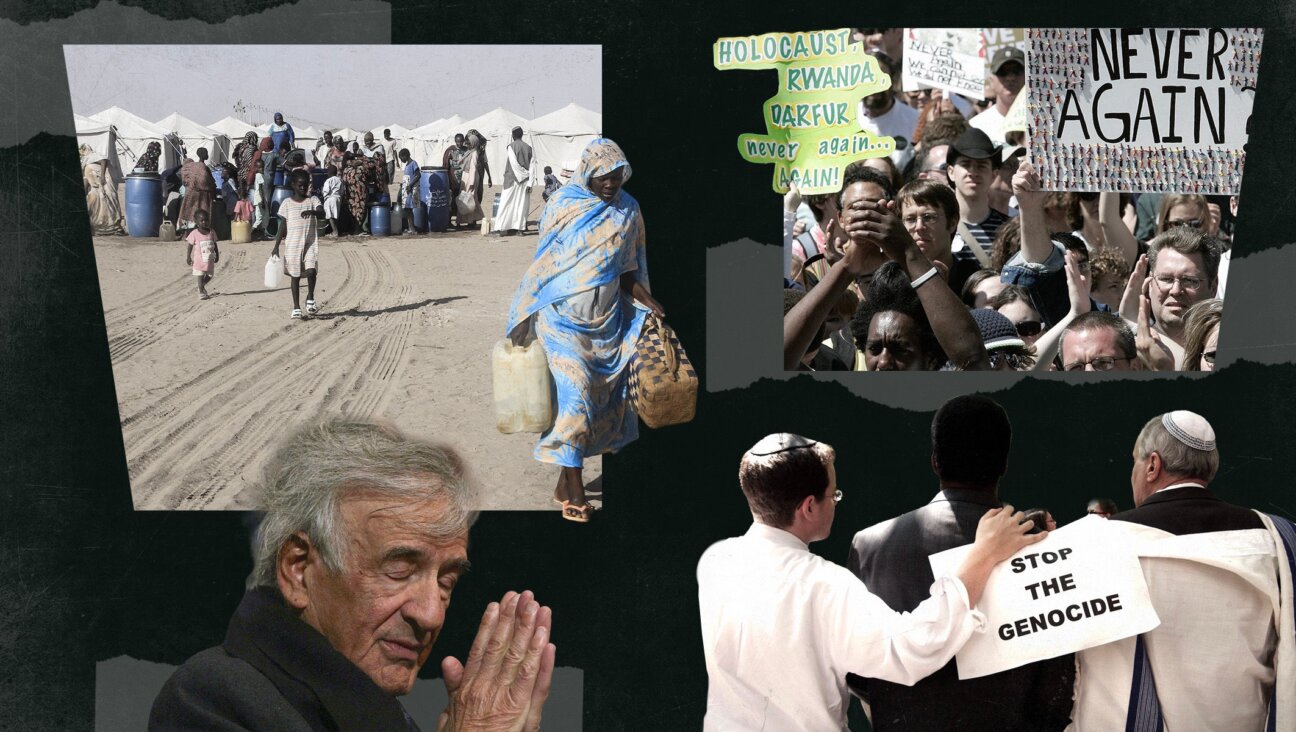

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

WASHINGTON — When Nordea Bank, a large, Stockholm-based financial services firm, got word that it had been blacklisted by the state of Illinois for boycotting Israel, top officials at the company were genuinely perplexed.

“It’s strange, very strange,” Sasja Beslik, head of responsible investments at Nordea Asset Management, told the Forward. “I don’t know how they reached their conclusion. They must be misinformed.”

According to Beslik, the bank had, in fact, undertaken a review of its investment policies toward Israel in 2014 and in the end explicitly concluded that there was no reason to boycott the Jewish state, or even exclusively Jewish settlements in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. And it declared this publicly.

But that is just one of numerous anomalies to emerge from the list compiled by the Illinois agency tasked with implementing the nation’s first state law against the movement to boycott, sanction and divest from Israel for its policies toward the Palestinians.

The law, which was passed by legislators and signed by Gov. Bruce Rauner last summer, established a state investment policy board charged with preparing a list of companies that boycott Israel or “territories controlled by the State of Israel.” The language is meant to encompass exclusively Jewish West Bank settlements established by Israel that the United Nations Security Council and other international bodies have declared illegal under the Geneva Conventions.

On March 18, the board, which developed its list primarily through online Google searches and other public information, published a tally of 11 foreign-based companies. Under the new law, all state-owned Illinois pension funds are now prohibited from investing in these firms. But none of the companies listed was contacted beforehand. And research work behind the list seems sketchy, at best, leaving open questions regarding the definition of actions that could be viewed as adherence to BDS. Moreover, American companies identified as engaging in BDS were excluded from the list.

Of the 11 listed companies, two claim that their decisions to cut investments in Israel were made purely for business reasons; Nordea insists it stayed involved in Israel and rejected calls for boycott altogether, and most of the other firms made clear their boycott relates only to companies and products from West Bank settlements. Only one company on the list has a clear policy of boycotting Israeli companies within the country’s internationally recognized borders as they existed prior to the 1967 Six Day War, in which Israel took control of the Palestinian territories from Jordan.

This is the process that left Nordea and some of the companies on the list scratching their heads.

Nordea popped up on the BDS radar in 2014, when, after fielding questions from pro-BDS activists, it asked two Israeli banks it had business ties with for details about their West Bank investments. Beslik visited Israel twice to examine his firm’s investments there. The Scandinavian firm asked the Israeli banks with which it does business to detail their work in the West Bank. But in June 2014, Nordea publicly concluded that there was no reason to boycott Israel.

“In some cases,” Nordea declared then, with reference to one of the Israeli banks with which it worked, “Hapoalim bank scored more highly in terms of corporate and social responsibility than many Nordic companies.”

“We do not boycott Israel and we do not boycott Israeli companies,” Beslik told the Forward, explaining that Nordea found “no evidence” that its investments in Israel “violate international law.”

But it appears that Nordea’s decision to ask questions about its Israeli investment partners’ policies and practices was enough to get it on the Illinois divestment blacklist. And under the new law, neither it nor any of the other blacklisted companies has any legal recourse in the courts to get itself removed.

Mitchell Goldberg, chairman of the state appointed group charged with identifying companies cooperating with BDS, did not respond to several messages requesting an interview.

BDS opponents view Illinois’s publication of its list as a major milestone in their battle against BDS, which has emerged in recent years as a major rallying point for the American Jewish community. Jewish groups have raised millions of dollars for campus anti-BDS activity and for a concerted drive for legislation targeting companies and institutions participating in any form of boycott against Israel.

So far, in response to that effort, three other states have signed similar legislation into law, and 20 more are considering bills that demand anti-BDS action. As with Illinois, most of these laws and bills target boycotts against Jewish settlements in the West Bank along with BDS against companies within Israel proper.

“It shows that states are treating this as discriminatory conduct and that companies that give in to BDS will face consequences,” said Eugene Kontorovich, a professor of constitutional and international law at Northwestern University who has been involved in formulating anti-BDS laws in several states. “They’re saying to these companies that they’ll have an even bigger headache if they give in” to pressure from pro-BDS activists.

On the congressional level, success has been more modest. Two pieces of legislation passed last year with support from the American Israel Public Affairs Committee included language demanding that the administration act against boycott efforts, whether in Israel proper or in the West Bank settlements.

In February, President Obama signed the legislation into law, but added a signing statement expressing his view that parts of the law “conflating Israel and ‘Israeli-controlled territories’ are contrary to long-standing bipartisan United States policy, including with regard to the treatment of settlements.”

The Illinois law, which was approved unanimously in both the state Senate and the state Assembly, established a state investment policy board that was charged with preparing the list of companies that boycott Israel, along with lists of firms doing prohibited business with Iran and Sudan, both of which the State Department classifies as state sponsors of terrorism. The law requires all state-funded retirement funds “to identify all companies that boycott Israel” and to divest their holdings from these companies.

Boycotts, according to the language of the law, are actions “politically motivated and intended to penalize, inflict economic harm on, or otherwise limit commercial relations with the State of Israel or companies based in the State of Israel or in territories controlled by the State of Israel.”

The law is limited to state pension fund investments. It does not go as far as bills in some other states that ban any government contracts with companies adhering to BDS. The law compels Illinois’s five state-owned pension funds to refrain from investing in any companies on the blacklist and, if they have already done so, to sell those shares.

The board entrusted with implementing the Illinois law consists of three representatives of state pension funds and four members appointed by Rauner. Within this body, the three-person subcommittee tasked with identifying companies that boycott Israel consists of Andrew Lappin, a real estate developer who is on the board of the Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting in America, a group that fights perceived anti-Israel bias in the media, and the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, which works with evangelical Christians; Alicia Oberman, a board member of Jewish Student Connection, which runs programs for Jewish teens in schools, and Goldberg, the subcommitte’s chairman and a Chicago lawyer who served as president of his Orthodox synagogue.

To compile the list, Lappin said in a phone interview, the subcommittee relied on openly available sources, primarily publications from pro-BDS groups “that boast about their exploits.” The subcommittee also relied on information from pro-Israel organizations that list companies involved in boycotting Israel.

The group initially listed 14 companies but then decided to drop those based in the United States and keep only 11 international firms.

Besides Nordea, two companies on the list, Belgium’s Dexia bank and the British G4S security firm, state that they sold off their investments in Israel purely for business reasons, although BDS groups claimed the moves were in response to their pressure.

Only after publishing the list did the Illinois board hire an outside contractor to examine it and seek responses from the blacklisted companies. Lappin said he did not see any problem with launching this inquiry after the list had already taken effect. “The odds of these 11 companies not making the list are pretty darn low,” he said, “because we did it based on their own declarations and on reports of NGOs,” or nongovernmental organizations.

Only one of the companies listed, the British communications firm FreedomCall, was clearlyinvolved in a boycott move targeting all of Israel when, during the 2008–9 Gaza War, it informed its Israeli counterpart of its intention to sever ties because of that Israeli military operation.

Most of the others refused to invest in companies operating in West Bank settlements as part of a “responsible investment” policy. These include:

• Two subsidiaries of the Norwegian KLP group that pulled their investment from an international concrete company that operated quarries in the West Bank.

• A Dutch bank that disinvested from the Jerusalem light rail project, which included work in East Jerusalem. Israel unilaterally annexed East Jerusalem after the 1967 Six Day War, and later expanded its boundaries into the West Bank. (The international community has rejected both of those actions as illegal.)

• Denmark’s largest bank, Danske, which announced it would not invest in settlement companies or in certain defense contractors in Israel and several other countries.

• Two supermarket chains, one in Luxemburg and the other in the United Kingdom, that announced they will not carry products made in West Bank settlements, and a South African supermarket supplier that stopped imports of dates grown by settlers.

The concrete economic damage the firms face from inclusion on Illinois’s blacklist is limited, given that most of them were unlikely to be in the investment portfolio of Illinois state pension funds in the first place; even if they were, the divestment wouldn’t make much of a dent in their financial standing.

It could, however, have a reputational impact. And in the long term it could have even an economic impact as other states pass their anti-BDS laws and seek sources for compiling their own lists of prohibited companies. Florida is the latest to sign such a bill into law, and others are expected to follow later this year.

“Other states will use [Illinois’s list] as their building blocks for moving forward,” Kontorovich said, “Illinois was the first, so others will look to them.”

Contact Nathan Guttman at [email protected] or on Twitter, @nathanguttman