When Biblical Gender Is Lost In Translation

Image by iStock

We find gender-bending language in the Torah, in the greater Hebrew Bible, as well as in later Hebrew literature. And I am hardly the first one to notice this. Bible scholars, critics, and translators of later Hebrew works have all drawn attention to the phenomenon.

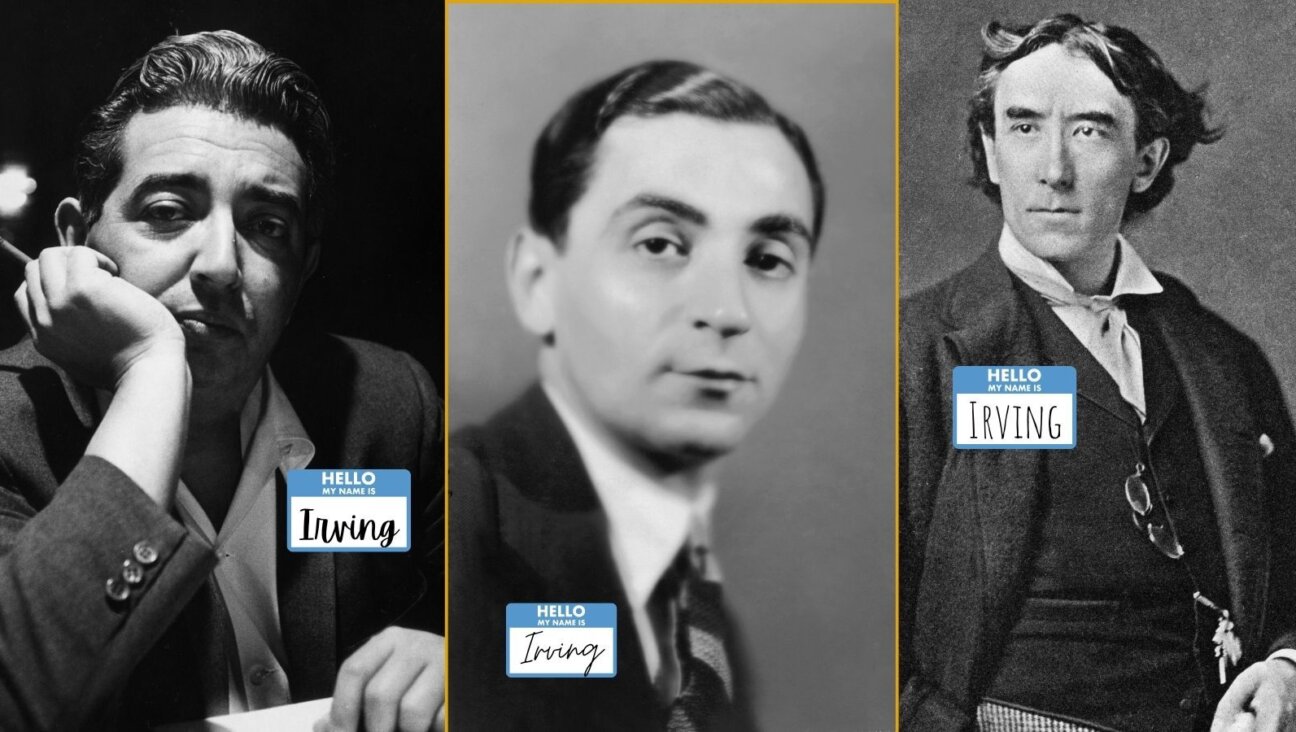

In his 1990 bestseller “The Book of J,” Harold Bloom noted that the author of the J strand of the Pentateuch presents God as both “mother and father;” indeed as a gender-bending “mothering father,” even as God “stands beyond sexuality.”

The 1989 poetry collection Rift, by the master translator and poet Peter Cole, was, he told Paris Review, “a semiconscious translation of everything I was absorbing—the blurring of secular and sacred planes, heightened attention to the auditory, gender bending in the Hebrew verse and its grammar…”

As long ago as 1946, Bible scholar Edwin Broome had noted pervasive grammatical gender-bending in the Book of Ezekiel, and concluded that the prophet must have suffered from “gender confusion.”

But gender-bending language in the Hebrew Bible was the subject of commentary long before the twentieth century.

As long ago as the eleventh century, the great Torah commentator Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo ben Yitzchak, d. 1105) felt compelled to explain why Moses had addressed God as at, the second person feminine singular word for “you” (Numbers 11:15). Rashi speculated that Moses had grown “weak” — the suggestion being that he was too tired to utter the two-syllable word atah, the second person masculine singular word for “you,” and had broken off after the first syllable. Rashi’s far-fetched explanation is not as interesting as the fact that he felt compelled to address gender-bending language in the Torah.

Even a fairly straightforward text presents translation challenges. One who is perfectly fluent in two languages will still struggle to capture the flavor of the original text’s cadences, alliteration, allusions and word-plays. There is no way to do this perfectly. Sometimes there is no way to do it well.

And when a text’s meaning has been intentionally obscured… all bets are off. Such is the case with the Hebrew Bible. The second century BCE scribe Ben Sira wrote about the Torah’s many “twists,” “obscurities,” “riddles,” and “hidden things” (Ben Sira 39: 1- 8). And he pushed the curious away: “You have no need of hidden matters,” he wrote (Ben Sira, 3: 21-24).

Ben Sira’s grandson translated his grandfather’s work into Greek, and put his readers on notice that the difference between his grandfather’s original Hebrew text and his own Greek translation “is not small” (Ben Sira, Prologue, 15).

Sometimes intentionally, always inevitably, much gets lost in translation. Not for nothing did the rabbis declare the day on which the Torah itself was first translated (into Greek) an annual day of mourning.

Reading the Torah in translation, we would do well to acknowledge that a vast “space” exists between a translation and an original text. As the Forward’s own Aviyah Kushner, author of the highly illuminating book The Grammar of God has written, “this particular space between languages matters.”