When Jews — and Everyone Else — Learned How To Have Fun

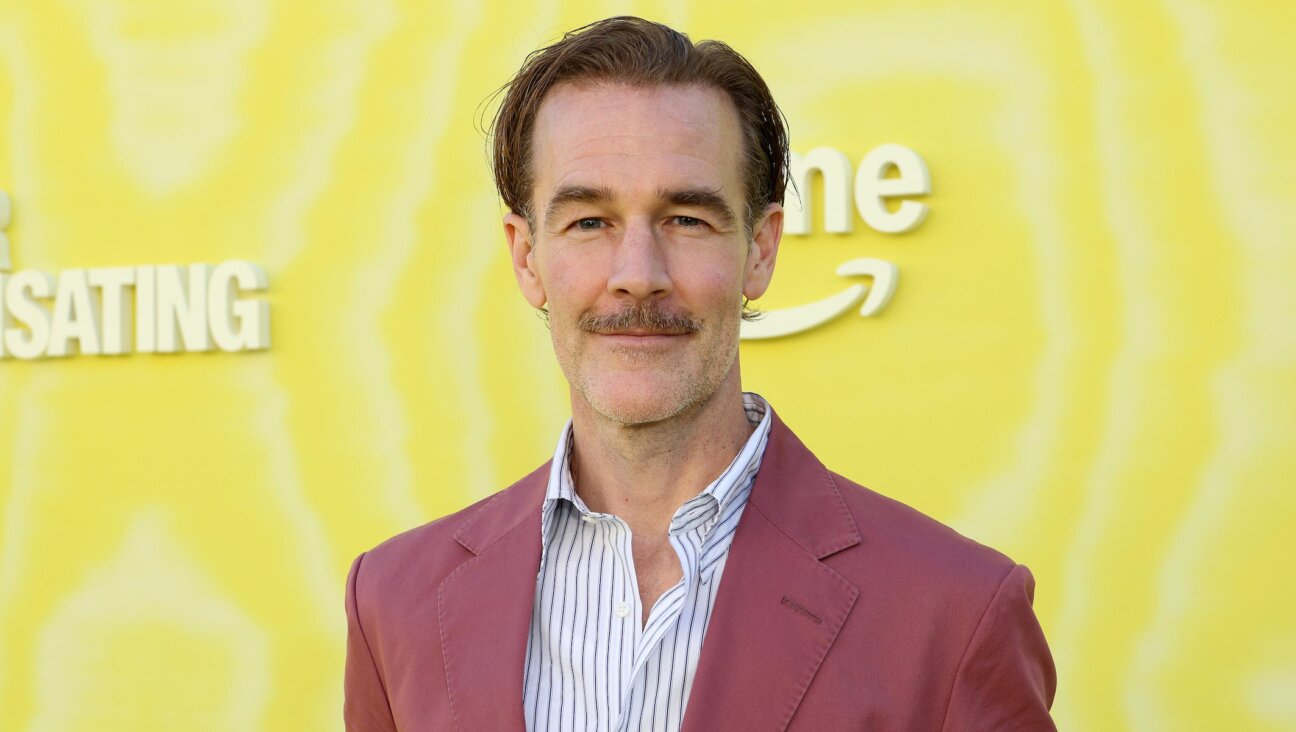

Love Jones: A scene from Henry Fielding’s ‘Tom Jones,’ which features a character who was ‘a great lover of what is called fun.’ Image by Getty Images

Beth Kissileff writes:

“A rabbi recently said to me that there is no word for ‘fun’ in any Jewish language because Judaism is purpose and goal oriented. I said, ‘But there is keyf in Hebrew,’ and he said, ‘No, that’s from Arabic.’ Was the rabbi right?”

On first thought, he would appear to be. If you look in dictionaries of the three major modern Jewish languages — Hebrew, Yiddish and Ladino — you won’t find in any of them the equivalent of “fun” in a sentence like “The pillow fight was fun.” Uriel Weinreich’s English-Yiddish Yiddish-English Dictionary offers us three Yiddish words for “fun”: hanoe, which means “pleasure” or “enjoyment”; khoyzek, which is fun made of someone or something, and katoves, which means “jest” or “lark.” Elli Kohen and Dahlia Kohen-Gordon’s Ladino-English English Ladino Concise Encyclopedic Dictionary gives the sole word shuki, as in the Ladino phrase tomar shuki, to make fun of. And Hebrew keyf, which does denote fun of the pillow fight variety, is indeed a 20th-century Israeli borrowing from Palestinian Arabic.

In traditional Arabic, however, keyf does not mean “fun,” either. It means “pleasure,” a state of well-being or a narcotic drug that can induce such a state. (Hence “kif,” marijuana, which entered English from the Arabic of North Africa.) In the expression ala keyfak, “for your pleasure,” meaning “the best,” it has been borrowed by Israeli Hebrew, too: “Ekh haya ha-seret?” “Ala keyfak!” “How was the movie?” “Fabulous!”

And here’s the rub. It’s not just Jewish languages that traditionally have lacked words for “fun.” In no language that I know of does a pre-modern word for “fun” exist — if, that is, what we mean by “fun” is not simple pleasure or enjoyment (for which all languages, including Jewish ones, have always had words), but an entertaining form of them that is engaged in entirely for its own sake, without, as our rabbi would say, any ulterior purpose. We do not ordinarily think of eating dinner at home as being fun, since as enjoyable as the food may be, it serves the goal of nourishing our bodies. A barbecue or fondue, on the other hand, can be fun because it overshoots this goal by introducing pleasures — romping on a lawn with the children, getting one’s fingers hilariously sticky with cheese — that are not necessary for the goal’s fulfillment. Fun, to be fun, must have an element of play that is devoid of functional value.

Of course people, and not just children, have always had fun; the ancient Romans had it at their circuses, and medieval Jews had it in their Purim shpiels. Yet fun not just as an occasional diversion from the serious business of living, but as a generalized activity that is one of a society’s main pursuits (as it is a pursuit of ours), is a concept found only in places in which many or most people have a considerable amount of leisure time — and no such place existed before the advent of modernity. It is no accident that the word “fun” first appeared in English in the 18th century and was still far from widespread by the middle of it, as evidenced by Henry Fielding saying of a character in his 1749 novel “Tom Jones”: “He was a great lover of what is called fun.” Clearly, Fielding assumed that not all of his readers would know the word.

The same is true of other European languages. In some, the meaning of “fun” evolved in words that originally meant (and still may mean) “jest” or “joke,” like German Spass. In others, there is no precise way of saying “fun” to this day. Open a French dictionary and you’ll be told that “to have fun” is bien s’amuser, which is actually more like “to have a good time.” The two can be, but needn’t be, the same. I can have a good time accompanying my elderly aunt to a classical concert, but I wouldn’t necessarily be having fun.

If Jewish languages, then, have no traditional word for “fun,” they’re hardly unique. And yet, come to think of it, Yiddish does have an expression that might be translated as “fun” — and that, ironically, might be cited on our rabbi’s behalf. This is goyishe nakhes, literally, “gentile satisfaction.” Nakhes, as many of you know, is the satisfaction you get from your own or others’ successes: a prize you’ve been awarded, your daughter’s graduating medical school, your grandson’s being praised by his judo teacher. Goyishe nakhes is nakhes gotten from things that no sensible Jew would do: shooting marbles when you could be studying Talmud; rafting down the Amazon though there’s plenty of water in the bathhouse; hitting people over the head with pillows that were made to be slept on.

In short: having fun. Judaism scorned the notion of fun because it isn’t what God put us in this world for. About that our rabbi is right. He’s wrong, though, if he thinks that Christianity and Islam were any different. Words for fun appear in languages as religious zeal loses its hold on their speakers — and as they have the time to have fun.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]