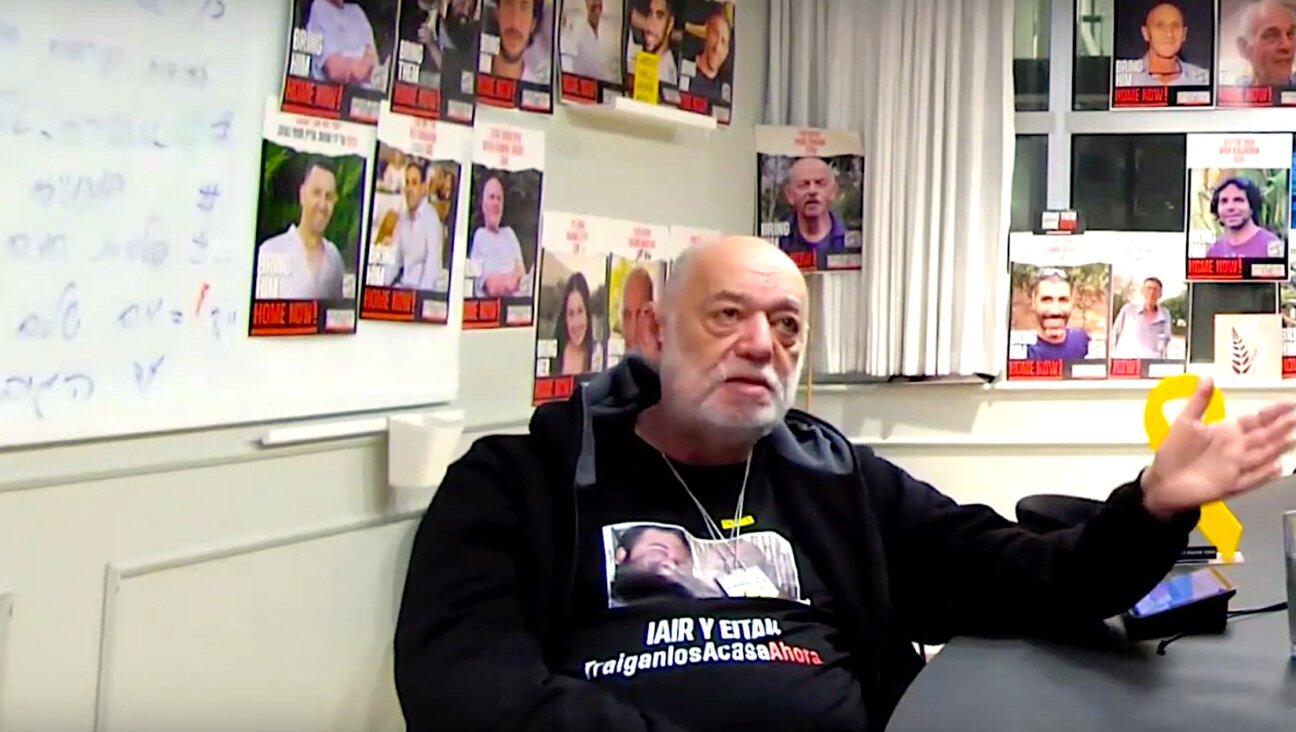

George McGovern Dies at 90

Image by getty images

Former U.S. Senator George McGovern, a liberal Democrat and fierce opponent of the Vietnam War whose 1972 presidential race against Richard Nixon led to one of the worst electoral defeats in U.S. history, died on Sunday at the age of 90, his family said.

The McGovern family said he died Sunday morning at Dougherty Hospice House in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, surrounded by family and friends. He had suffered from a combination of medical conditions due to age that had worsened in recent months.

Although he was giving speeches, writing and advising beyond his 90th birthday this summer, McGovern had been hospitalized several times in the past year after complaining of fatigue after a book tour, a fall before a scheduled television appearance, and dizzy spells.

“We are blessed to know that our father lived a long, successful and productive life advocating for the hungry, being a progressive voice for millions and fighting for peace,” a statement released by his family said.

Former President Bill Clinton and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said of him: “The world has lost a tireless advocate for human rights and dignity.”

McGovern, who served in the Senate for South Dakota from 1963 to 1981, challenged Nixon in 1972 on a platform opposing the war in Vietnam. He suffered one of the most lopsided defeats in U.S. history, taking only 37.5 percent of the vote and winning only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

Later, as Nixon’s presidency unraveled in the Watergate scandal, bumper stickers saying, “Don’t blame me, I’m from Massachusetts,” and buttons saying “Don’t blame me, I voted for McGovern,” appeared.

McGovern was not the first choice of the Democratic Party leadership to serve as their standard bearer in the 1972 race, and his nomination marked a shift away from the influence of party overlords and toward voters determining the nominee through state primaries and caucuses.

His platform not only called for ending the Vietnam War, but greatly reducing defense spending and amnesty for draft evaders. During the campaign he proposed what came to be known as “demogrants” – a $1,000 payment to Americans to guarantee them income and replace some welfare programs – but he eventually dropped that from his campaign.

McGovern’s failure to vet his vice presidential running mate Thomas Eagleton thoroughly cast doubts on his judgment when Eagleton announced he had hospitalized himself three times for “nervous exhaustion and fatigue.”

He picked former Peace Corps Director Sargent Shriver, a Kennedy family in-law, as Eagleton’s replacement but the damage was done.

McGovern found himself facing a well-oiled Republican political machine headed by Nixon.

“I have loathed Richard Nixon since he first came on the national scene wielding his red brush in 1946,” McGovern said in his autobiography, referring to Nixon’s anti-Commnist efforts at t he start of the Cold War in the decade immediately after World War Two.

HUMANITARIAN WORK

But McGovern’s legacy stretches well beyond his terms in Congress and presidential bids, to social issues, including world hunger and AIDS, said Donald Simmons, director of the McGovern Center for Leadership and Public Service at Dakota Wesleyan University in Mitchell, South Dakota.

“Outside of the U.S., he is known for his real humanitarian efforts and I think that will be one of his greatest long-term legacies,” Simmons said in a telephone interview on Wednesday.

The son of a Methodist minister, McGovern was born July 19, 1922, in Avon, South Dakota, and his family moved six years later to Mitchell, where he graduated from high school in 1940.

McGovern flew combat missions over Europe as a B-24 bomber pilot during World War Two, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1956, and re-elected two years later. After McGovern lost a U.S. Senate election in 1960, President John F. Kennedy named him the first director of the Food for Peace Program.

He also ran for president in 1968 after the assassination of front-runner Robert F. Kennedy and entertained a short-lived bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984.

McGovern said he had moved on from his 1972 defeat, but when another defeated Democratic presidential candidate, Walter Mondale, asked him in 1984 how long it took to get over losing in a landslide, McGovern replied: “I’ll let you know when I get there.”

As a soft-spoken academic – he was a history and political science professor – and a decorated pilot, McGovern did not fit the model of many of the leaders of the anti-war movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

He became a campaigner for world food issues in his post-politics life. He wrote several books, including an autobiography, the story of his daughter’s struggle with alcoholism, and “What it Means to Be a Democrat,” which was released last year.

McGovern also continued to make television appearances and write editorials and commentaries and often lamented what he saw as a lack of a true public debate on policy issues from members of both parties.

In 2000, President Bill Clinton awarded McGovern the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

In October 2007, McGovern endorsed Senator Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination but seven months later switched to Senator Barack Obama and urged Clinton to drop out of the race.

McGovern’s family has encouraged people to give to the charity Feeding South Dakota (www.feedingsouthdakota.org) if they wish to offer donations in memory of the senator.

McGovern and his wife Eleanor, who died in 2007, had five children.

Services will be held in Sioux Falls, the family said. Details will be announced shortly.

In the last book, McGovern summed up his political philosophy by writing: “Above all, being a Democrat means having compassion for others. It means putting government to work to help the people who need it. It means using all available tools to provide good health care and education, job opportunities, safe neighborhoods, a healthy environment, a promising future.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO