In the rise and fall of a Jewish politician named Mandel, a cautionary tale for Josh Mandel

A Slow Rise to Power: Named to a cabinet position — for the lowly postal service — Georges Mandel became Interior Minister in 1940. By Wikimedia Commons

Though he was Jewish, he won fame as an archly conservative nationalist; while he graduated from a state, not an elite university, he believed he was destined for high political office; though his fellow party members disliked him, they also acknowledged his determination; caught more than once in telling lies, he confused his brashness with truthfulness; while he served his country in war, he also made sure that experience would serve his political ambitions.

Meet not just Josh Mandel, but also Georges Mandel, one of the most fascinating French politicians in a nation that, for better and worse, had no shortage of them.

There is probably no need to introduce you to Josh Mandel, the native Ohioan who, once again, is running for political office. Having lost to Sherrod Brown in his campaign for senator, Mandel now has his sights set on the Senate seat that, thanks to Rob Portman’s retirement, has opened for 2022. In a frantic race to the bottom with J.D. Vance — the self-avowed hillbilly who, like his opponent, is as mendacious as he is shameless — for the GOP nomination, Mandel released a campaign video in September that caught the media’s attention.

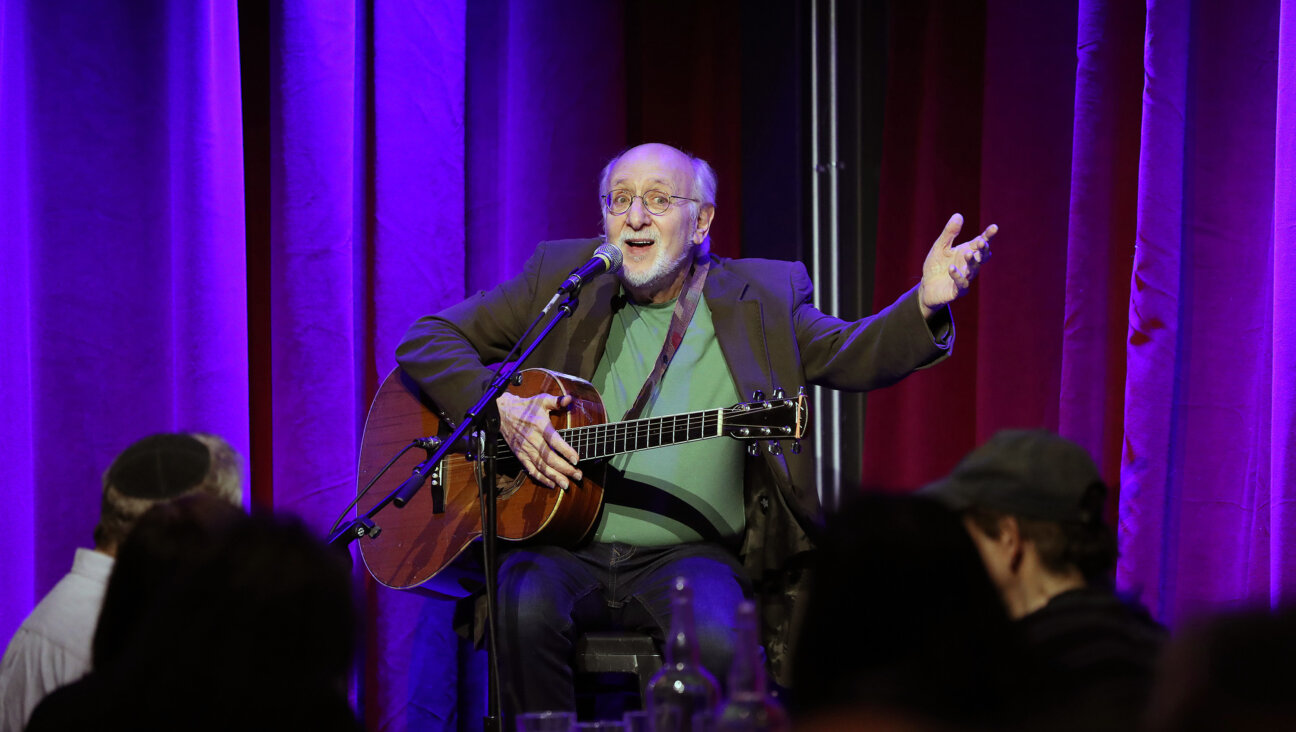

Big Aspirations: Josh Mandel has his eye on Rob Portman’s Senate seat. By Wikimedia Commons

The video framed Mandel standing in the middle of a corn field, in front of a Trump sign he had “literally” just found. Gesturing woodenly with both hands, he declared his “blood was boiling in rage” over the decision by Joe Biden — he refused to use Biden’s elected title because Donald Trump was still his president — to impose a vaccine mandate for large businesses. Exhorting his fellow Ohioans not to “comply with this tyranny,” Mandel declared “When the Gestapo show up at your door, you know what to do.”

Here’s the awful rub. While the Gestapo will not show up at Josh Mandel’s door, it did show up at Georges Mandel’s. His prison door, it happens. That visit — and subsequent execution of Georges Mandel — reveals the difference between the promise of French republicanism and preposterousness of American Republicanism.

Born Louis Georges Rothschild, the young man — whose father, a struggling tailor from Alsace, was several degrees removed from the Rothschilds — changed his name to Mandel to make this distinction clear. Though he graduated from a prestigious lycée in Paris, he never attended — despite his subsequent claim — the École normale supérieure, the even more prestigious university. Instead, Mandel was galvanized, like his older contemporary Léon Blum, by the Dreyfus Affair and threw himself into politics.

Unlike Blum, who became the leader of France’s Socialist Party, Mandel instead pivoted hard to the political right. Though he was now keeping company with virulent antisemites like Maurice Barrès and Léon Daudet, Mandel never wavered in his nationalism. Rejected for reasons of bad health by the draft board in 1914, Mandel became the indispensable assistant to the fierce republican nationalist, Georges Clemenceau. In the dark days of 1917, Clemenceau, rightly known as “le Tigre,” became prime minister by his vow that he would “to carry on the war and nothing but the war. The nation will know it is defended.”

As Clemenceau’s cabinet chief, Mandel proved his equal. In part, this was due to his intelligence. As one contemporary observed, Mandel “has read everything, the philosophers, the moralists, and, in particular, the historians.” In part, it was due to his ruthlessness; when not breaking worker strikes, Mandel was berating the “defeatists” who sought a way out of the endless bloodbath.

Between the world wars, Mandel, breaking free of The Tiger, ran for parliament and, after two losses, won a parliamentary seat. He quickly established himself as the most ambitious and brilliant, but also and not coincidentally its most feared and isolated member. He always did his homework, always knew his dossiers, and always thought he knew better. For this reason, though the consensus was that he the most qualified man to become prime minister, he was among the least liked.

Named to a cabinet position — for the lowly postal service — for the first time only in the mid-30s, it was not until 1940 that he became Interior Minister. It was (and, with the Treasury, remains) the most powerful of all ministries; responsible for the nation’s internal security, the Interior Minister is, in effect, le top flic, or cop, in France.

Of course, becoming minister of an interior besieged by German Panzers and Stukas is perhaps not the plum job it otherwise be. Yet when he was offered the position in May 1940, Mandel accepted it the spirit of his mentor Clemenceau. Along with the Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud and a newly appointed Under-Secretary of State by the name of Charles de Gaulle, Mandel resisted the faction, led by Philippe Pétain, that wanted to sue for peace. Within days, however, their furious struggle to carry on the war proved futile. On June 17, Pétain — given full powers by the parliament, took to the airwaves that he was offering the “gift of his person” to a battered France and seeking peace terms with Nazi Germany.

When the unthinkable became the irremediable, Mandel faced an existential choice. Winston Churchill, deeply impressed by Mandel’s implacable and imperturbable character when they met in France in May, baptized him “Mandel le grand.” Tellingly, Churchill believed Mandel, not de Gaulle, was the man of destiny and tried to persuade to cross the Channel and lead France’s government-in-exile.

Mandel believed otherwise, convinced that a French Jew who quit the country in full debacle would be accused of cowardice. For this reason, de Gaulle recounts in his “Mémoires de guerre,” Mandel asked the general to meet with him privately. “In a tone,” de Gaulle wrote, “whose gravity and resolution impressed me,” Mandel reminded him the war had only just begun. “You will have great duties to perform, General! But you will perform them with the advantage of being the one man among us all, a man with an unblemished reputation.”

In the end, de Gaulle was the man of destiny. As for Mandel, destiny led him to Morocco, where he intended to carry on the war. Instead, arrested by Vichy officials, he was packed off to France where show trial summarily condemned him to life imprisonment for treason. Two years later, when German troops occupied what had until then been France’s “free zone,” Mandel was transferred to the concentration camp of Buchenwald where Blum had already been installed.

In the summer of 1944, just weeks after the Allied landings at Normandy, the Germans handed Mandel back to a quickly unraveling Vichy government. Imprisoned at the notorious Santé prison in Paris, Mandel was taken July 7 from his cell by miliciens — Vichy’s wretched imitation of the SS — who drove the prisoner to the nearby forest of Fountainebleu, pulled him from the car and shot him dead. Perhaps because he was Jewish, perhaps because he was a republican, perhaps for both of these reasons.

In front of the cemetery of Passy, where lies buried this French Jew who gave his life for the republic, runs a grand boulevard renamed Avenue Georges Mandel in his honor. It is hard to imagine that Columbus will one day rename a street after the other Mandel to honor a Republican busy defending Donald Trump, even if it costs us our Republic.

Robert Zaretsky teaches at the University of Houston. His latest book is “The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas.”