‘A terrible responsibility’: In today’s U.S., patriotism is essential — but not easy

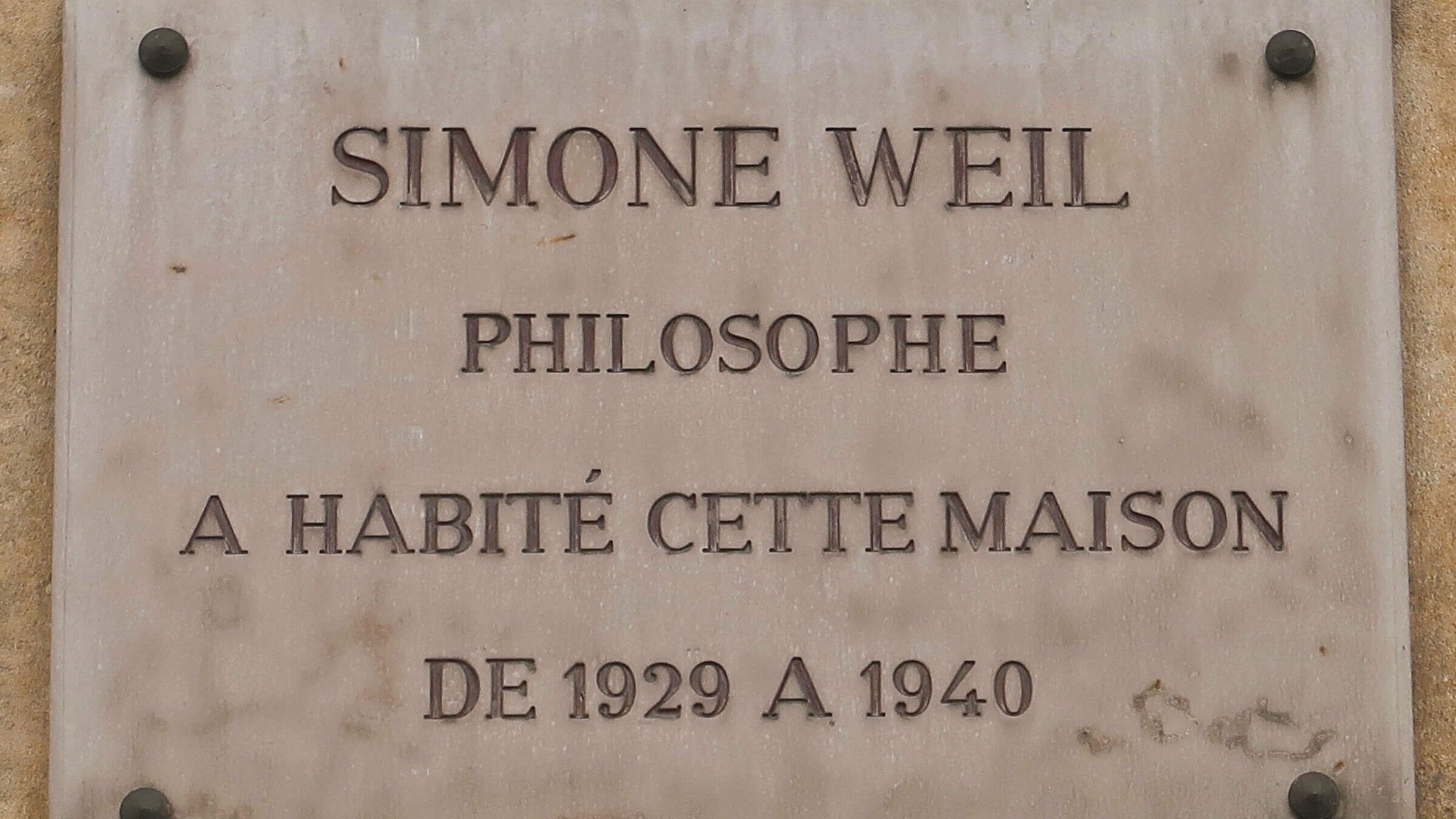

During WWII, the philosopher and activist Simone Weil gave patriotism a new definition — one now more crucial than ever.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

In early July 1942, a 30-something French Jewish woman and her parents, having fled occupied France months earlier, disembarked in New York City. While the parents were still unpacking, the daughter began to write letters to friends, acquaintances, even strangers to help her return to France.

To an English officer she heard on the radio discussing France, she poured out her heart in near-fluent English.

“It is a very hard thing to leave one’s country in distress,” she Weil wrote. “Although my parents, who wanted to escape antisemitism, put a great pressure upon me to make me go with them, I would never have left France without the hope that through coming here I could take a greater part in the struggle, the danger and the suffering of this war.”

Simone Weil, the author of the letter, then tried to sell its recipient — as she had dozens of others — on the idea of creating squadrons of unarmed French nurses who, garbed in white and led by Weil, would be parachuted onto battlefields to tend to the wounded. Though the idea never got off the ground, Weil did manage to get as far as England toward the very end of that year, and join Charles de Gaulle’s Free French movement.

What she accomplished as a member of that movement laid the groundwork for a novel understanding of patriotism that has never been more relevant than today. This is true in France, where the extreme right-wing Rassemblement national, which identifies as the party of patriots, has just become the largest opposition party in parliament. And it is also true in America, where on January 6, 2021, insurrectionists waved American flags as they stormed the Capitol the culmination of an attempt to subvert a free and fair democratic election that continues to define our national discourse.

Weil’s task under de Gaulle was to read and respond to the ideals expressed by the many resistance networks for the shape of the government and constitution of a liberated France. She had, as well, her own ideas for her nation, which she set out in hundreds of pages of policy papers and projects. As with her nurses’ plan, the ideas expressed in these manuscripts — most of which were edited and published after the war (and Weil’s 1943 death) by Albert Camus — alternately dazzle and daze, toggling between shattering insights and the sheer impracticality, or undesirability, of acting upon them.

In his preface to the French edition of Weil’s last work, “L’Enracinement,” or “The Need for Roots,” Camus described Weil as “the only great mind (esprit) of our time.” The book is a mix of many notions that Weil, writing in her early thirties, was trying to develop, including reflections on the nature of “uprootedness” (no less a spiritual than it is a material condition) and the relationship between rights and obligations (unlike most modern political theorists, Weil insisted the latter must always take precedence over the former).

Most importantly for today, the book also features an impassioned plea on behalf of patriotism. Halfway through the book, in the midst of her discussion of uprootedness, Weil announces that “The world requires at the present time a new patriotism. And it is now that this inventive effort must be made, just when patriotism is something which is causing bloodshed.”

Eighty years after Weil wrote these lines, American readers might well feel that her “present time” is, in fact, our present time as well. But do they also feel that the time calls for patriotism?

For Democrats, the answer, too often, is a shrug of the shoulders. In a 2021 Gallup poll, while 87 percent of Republicans were either extremely or very proud to be Americans, only 62 percent of Democrats and 65 percent of independents felt the same way.

To be sure, patriotism seems like damaged goods at a time when a former president who has gone mad, his supporters who have gone murderous and their Republican Party, which has gone mute, all drape themselves with the American flag.

Yet it is no less certain, as Weil’s insights make clear, that patriotism, rightly understood, must be defended, not derided, by those who feel most concerned about its current direction.

“A terrible responsibility rests with us,” Weil wrote. “For it is nothing less than a question of refashioning the soul of the country, and the temptation is so strong to do this by resorting to lies or half-lies that it requires more than ordinary heroism to remain faithful to the truth.”

What does that “terrible responsibility” of patriotism look like? For Weil, it centered on compassion. Reflecting on the tragic state of her own country, she concluded that “compassion for our country is the only sentiment which doesn’t strike a false note at the present time.” Rather than acting on pride, which is selfish and exclusive, Weil believed we must learn to practice compassion, which is inclusive and selfless.

Weil dismissed those patriots for whom the nation is the ultimate source of value, one about which we think we can say, “My country right or wrong.” This is, she notes, “manifestly absurd.” Instead, Weil put nations in their place.

“The nation is a fact, and a fact is not an absolute value,” she wrote. It is the result of historical forces in which good and evil inevitably mingle. But it is also a source that allows each of us to achieve what is vital to all of us: “maintaining throughout the present the links with the past and the future.”

The French resistance, Weil reminds us, was concerned with more than just the defeat of Nazi Germany. Its members also sought to defeat the traditional understanding of the nation and nationalism. That task, already difficult, was compounded by the pall of shameless lies and willed blindness then enveloping France. “Our age,” she writes, “is so poisoned by lies that it converts everything it touches into a lie.”

Today, that line powerfully evokes all the damage wrought during the Trump years. But Weil was not content to simply call out the insidious effect of lies. She also, crucially, called our attention to our capacity for acting in truth.

To her, the most fundamental of truths was our unconditional duty towards others. “There exists an obligation towards every human being for the sole reason that he or she is a human being,” she wrote. From this claim, in her eyes, flowed all the public virtues we are called upon to acknowledge and act upon: liberty and equality, respect and responsibility.

These virtues, which remind us of our duties towards others, are as threatened in our time as they were in Weil’s. Though our country is full of talk about human rights, there is little talk about human duties. And yet, the recognition of the needs of our fellow citizens is the precondition to the reinvention of the nation.

What stronger and wider notion of patriotism, after all, could we offer than one that demands we forget about ourselves and instead focus on others? Rather than asking what the other can do for us, to tweak John Kennedy’s famous phrase, we must ask what we can do for the other.

This July 4, we could do worse than to recall Weil’s assertion, with the same self-assurance shown by the writers of our own Declaration of Independence, that duty “towards the human being as such — that alone is eternal.”

By placing human duties, and not rights, at the center of nationalism, Weil forces us to rethink the notion of the nation. At the very least, as I look at the American flag planted in our front yard, Weil deepens my understanding of my own patriotism.