5 Israeli prime ministers, 5 documentaries — but should you watch all 5?

A mini-festival on ChaiFlicks explores the lives of Ben-Gurion, Meir, Begin, Rabin and Sharon

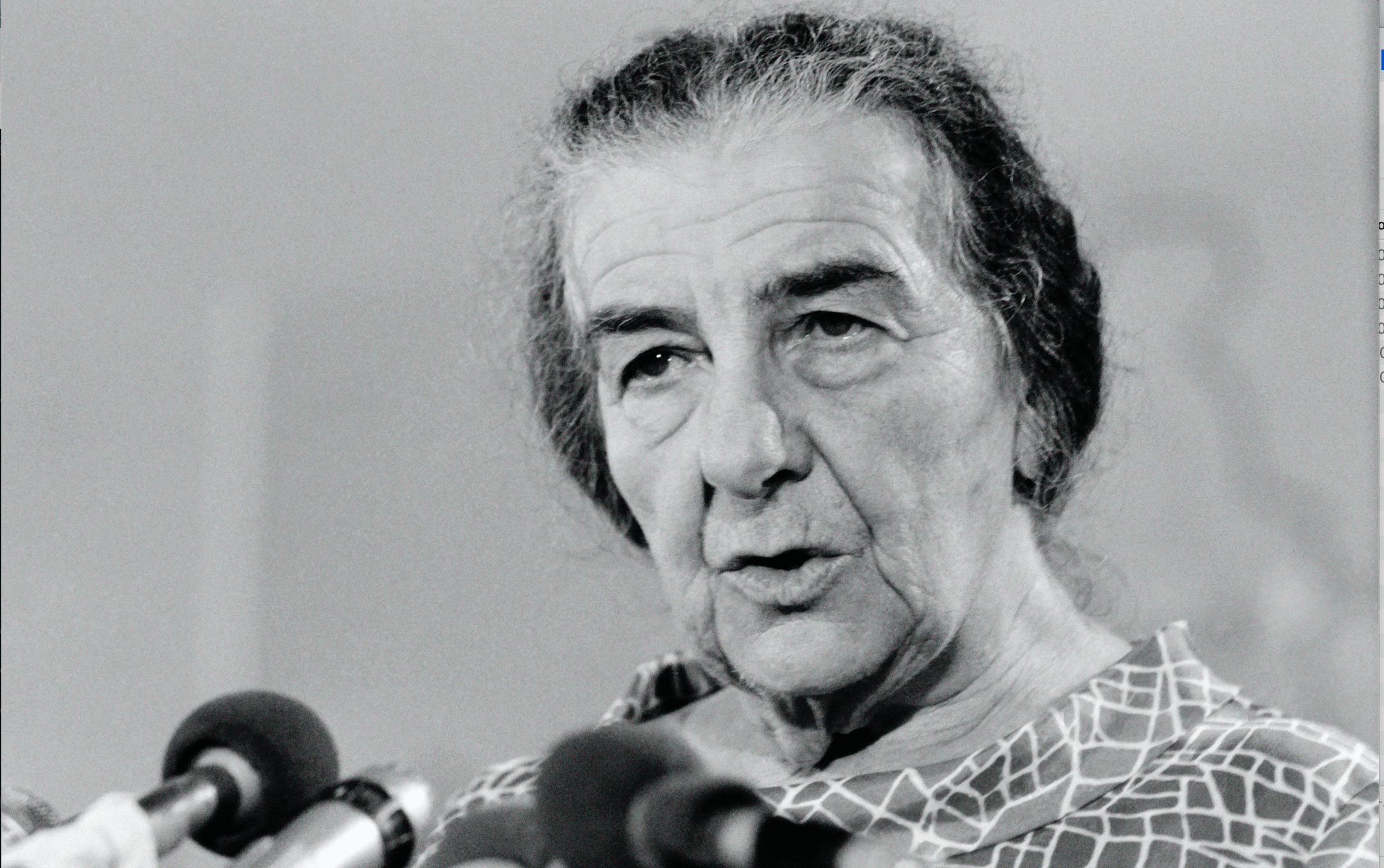

Golda Meir gives a press conference during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Photo by Getty Images

“The Prime Ministers” is a compelling five-part miniseries that probes the lives and careers of arguably the most significant Israeli political figures to head the Jewish state: David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, Menachem Begin, Yitzhak Rabin and Ariel Sharon.

Curated by ChaiFlicks, a streaming service specializing in Jewish-themed films and TV programs, the documentaries evoke the paradoxical, at times, antithetical characters that take on the qualities of fictional personalities who are at once dogmatic and practical; imposing in stature and also deeply relatable; guided by an overarching ideology and capable of fully reversing course.

Their presence at the helm shaped the Israeli narrative (and by extension regional if not global politics). The five films viewed individually and collectively illustrate the classic intersectionality of character and history.

The ongoing conflict and torment for all the prime ministers centered on issues surrounding security vs. peace and how each was defined. The existential threat of annihilation coupled with the long shadows cast by the Holocaust was ever-present.

Each film is a compilation of archival footage, newsreels, and radio recordings, interwoven with an array of interviews, including in-depth conversations with the title characters as well as allies, enemies and other various players and pundits. The notable exception is “Rabin, In His Own Words,” an autobiographical documentary that is literally just that.

‘Ben-Gurion, Epilogue,’ by Yariv Mozer

Often credited with being one of modern history’s great leaders, the Polish-born David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973) was a founding father of Israel and its first prime minister, a post he held until 1963 with a brief break in 1954. To this day he enjoys an almost mythic status identified with an Edenic Israel that bears no resemblance to Israel’s current reality or public image.

“Ben-Gurion, Epilogue” is based on a lost six-hour interview with the Israeli leader conducted at his isolated, modest home in the Negev Desert. The year was 1968 and he was 82 at the time, four months a widower, five years in retirement and five years before his death. Still, he was vital and engaged. He cut a vivid physical picture: short, squat, bald with a tuft of white bushy hair at the base of his head.

That interview was intended and released as a narrative feature in 1970, whereupon the film and the interview promptly vanished into a cinematic black hole. How that seminal interview was finally tracked down at the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive in Jerusalem, and its soundtrack discovered elsewhere, could be a movie all by itself.

Now edited to a tight 70 minutes, director Yariv Mozer’s fascinating documentary is structured around the “lost” interview as Ben-Gurion reviews his life, legacy and the future of Zionism. He offers many biblical references that support his views that Jews were destined to live in Israel. The prophet he admired most was Jeremiah, but for him Moses was “the greatest Jew.”

Ben-Gurion was a secular intellectual, a prodigious reader with a special affinity for “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” He did not believe in the cult of personality, maintaining that history was forged by many symbiotic forces.

“I did not guide Israel. I guided myself,” he once said. He embraced the trendy. He had a sly sense of humor and could be playful and iconoclastic even at his own expense. Under the guidance of New Age exercise guru Moshe Feldenkrais, Ben-Gurion learned to stand on his head.

His friends included Ray Charles, Albert Einstein, violinist Yehudi Menuhin, and Buddhist Burmese Prime Minister U Nu, with whom he happily sparred over their religious differences. Ben-Gurion wasn’t a great fan of meditation. He felt it was too “selfish.”

In some ways an aging hippie (a few have compared him to Yoda and even Norman Mailer), he was until the end a man of the earth who proclaimed that big cities were not good for humanity. Interspersed throughout we see him around his house, shoveling dirt or maybe it’s manure.

Most intriguing, he revealed himself to be an idealist and a pragmatist. He did not assume all Germans were Nazis or that their descendants were culpable for the Holocaust. Nonetheless in his wily negotiations with the West German government, he asked for Holocaust reparations, a move that appalled many Israelis who viewed it as “blood money.” Angry protests ensued. “History is not moral,” he cryptically pointed out.

He was a fierce Zionist until he wasn’t. He refused to dub himself a Socialist or Zionist. “I am a Jew who wants to live in peaceful place.” And in the wake of the Six-Day War, he was willing to compromise land, short of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, in exchange for peace. He did not feel Israelis were living up to their moral promise.

In the end he was a fatalist and a loner. Despite a frenetic political life that often pushed his family aside, the death of his wife rendered him “half a man,” he said. But his own death did not frighten him. “It wouldn’t change anything,” he said. *

‘Golda,’ by Sagi Bornstein, Udi Nir and Shani Rozanes

Golda Meir said she never finished a dream. She told her assistants to let all calls come through no matter what the time. She didn’t want to wake up to a national emergency only to discover she had slept through it. One thing is certain: She had no shortage of emergencies or interrupted sleep during her five years (1969-1974) as Israel’s fourth prime minister, and first and only woman in that position.

Meir was also the first woman in the world to serve as minister of foreign affairs, and the second elected as head of state. Among American Jews, she was both a feminist and a Jewish icon, dubbed “Queen of the Jewish people.” In Israel she was a polarizing figure identified with failure, humiliation and one of the country’s worst leaders ever. Both the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympics in Munich and the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which resulted in thousands of deaths, took place under her watch.

The filmmakers Sagi Bornstein, Udi Nir and Shani Rozanes were commissioned by German producers to make a film that explored the contradictions that defined her life, career and image. During the course of their research at the Israeli Television Archives, they uncovered, quite by accident, her last, never-before-seen television interview, which took place in 1978 several months prior to her death.

Lighting one cigarette after another, she spoke freely about her tenure as prime minister, by turns defending her decisions and voicing unremitting regret and guilt.

The now-digitized taped interview, which serves as the film’s centerpiece, is interwoven with testimonials offered by admirers, detractors, as well as those who came to appreciate her ambiguities and the uncharted waters she struggled to navigate.

“Golda” provides a striking depiction of an extraordinary woman, who could be a character of out of Greek tragedy. Her meteoric rise to power was followed by an equally meteoric descent at the corner of inevitability and randomness.

As a young child in her native Kyiv, she grew up in a troubled family, always fearful of pending pogroms. In 1906, at age 8, she immigrated to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where she excelled in school, becoming a teacher, a socialist and Zionist. In 1921, she and her husband made the move to Palestine and settled in a Kibbutz that was never to her husband’s liking. They were divorced and she became a single mother, raising two children on her own.

She wore many political hats on her trip to prime minister: secretary of the Working Women’s Council; signatory to Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948; minister of labor from 1949 to 1956. Before she retired due to poor health, she served for 10 years as Israel’s Foreign Minister. She later returned to politics supporting Prime Minister Levi Eshkol and, following his death in 1969, the Labor Party elected her as his successor.

Meir’s forward-thinking social programs did not extend to her views on people with darker skin. She had little sympathy for the impoverished Mizrahi Jews in Israel who, feeling discriminated against, became Israel’s Black Panthers. In one snippet, she questions them about what they do for a living, implying that their circumstances were of their own making.

She was even less disposed to empathize with Arabs in general and Palestinians in particular. She claimed Palestinians didn’t exist until the 1970s, which further tarnished her reputation.

The Yom Kippur War, which she claimed to have anticipated, was her downfall. Despite an Egyptian and Syrian buildup that was taking on Israeli borders, her many generals, including Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, felt there was no urgency.

She bowed to their authority and Israel was unprepared for the onslaught that followed. She was held culpable for the disaster and forced to resign. In one of the film’s most unsettling moments, she convened members of the Labor Party to announce her departure. “I’m at the end of the road,” she said quietly and walked out of the room alone.

Was she treated differently because she was a woman? Her colleagues made frequent references to her age and her gender, but she did not define herself in those terms, nor did she define herself as a feminist. More pointedly, she didn’t open doors to other women. There was not one woman in her cabinet.

She straddled treacherous territory. She had to remain aloof and cool, play the protective and stern mother (perhaps that’s who she was), but she could also be, well, almost flirtatious. When Ben-Gurion said she was the only man in the cabinet and meant it as a compliment, she coyly mused on whether he would be flattered if she said he was the only woman?

Her final chapter was unkind. No longer in office, she still did not sleep well. The phone was no longer ringing but nightmares of ringing phones persisted. The fears of imminent catastrophe lingered. On a poignant note, she said she hoped that any biography, to be published after her death, would be written with mercy.

‘Menachem Begin: Peace and War,’ by Levi Zini

Israel’s sixth prime minister, Menachem Begin, who served from 1977 to 1983, was the most striking embodiment of contradiction and is the most difficult of the five to parse, disputably in life, but unequivocally in Levi Zini’s documentary, “Menachem Begin: Peace and War.” On the one hand, Begin met with Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and signed an unprecedented and highly disputed peace treaty, earning both leaders Nobel Peace Prizes in 1978. On the other hand, Begin actively encouraged the expansion of settlements in the Occupied Territories until he reversed course.

In 1982, under his jurisdiction, Israel invaded Lebanon to stamp out Palestinian strongholds. From there, the war escalated, taking a devastating turn as Israeli forces landed in Beirut. The loss of life was catastrophic. Begin’s motivation remains unclear. Some say that he was duped by army leader Gen. Ariel Sharon, though Begin vehemently denied that.

Zini succinctly lays out the events, but no new insights are offered. Begin’s backstory, introduced at various points, arbitrarily it seems, clarifies little. We learn that, as a youth in Brest, Poland, he was a follower of Ze’ev Jabotinsky, founder of “revisionist” Zionism, a radical movement rooted in the idea that Jews should immigrate to Palestine and expand their presence and their acquisition of land.

The crusade culminated in the creation of the Irgun, a terrorist wing responsible for the bombing of the King David Hotel, the home base of the British military in 1946. Begin, who always referred to himself as a freedom fighter as opposed to a terrorist, was its leader. In the wake of the Holocaust where Begin lost most of his family, he was outraged that the British were not allowing more Jews into Palestine.

A revolutionary who morphed into a national ruler who, at least in appearance, brought to mind a well-dressed corporate CEO, would seem to be a great recipe for a gripping character study. But for whatever reasons, the film doesn’t gel. At no point does Begin emerge as a cohesive three-dimensional human being.

‘Rabin in His Own Words,’ by Erev Laufer

In the opening scene of Erez Laufer’s documentary, Yitzhak Rabin says this story will have a sad ending. Is his dark premonition about Israel or himself or both? Of course, most already know how his final chapter will unfold.

The film’s centerpiece is Rabin’s own commentary lifted from archival clips, letters, diaries and home movies, among other sources. But Laufer supplements this material with the backstory, shaping the portrait and narrative that emerges.

To some degree that’s true of every documentary, but more so here because this is a depiction not so much of a leader’s career or a chronology of historical events as it is an exploration of the private man behind the public mask and political role.

Born in 1922, the first Sabra-born Prime Minister was reared in a left-wing family and started his adult life as a farmer. But he was tapped for a military tour of duty (by Moshe Dayan no less), and moved up the hierarchy to head the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), where he was a major player first in the war for independence in 1948 and then in 1967’s Six Day War. A stint as Israeli’s ambassador to the U.S. from 1968 to 1973 followed, and one year later, in the wake of Meir’s political demise, he succeeded her as prime minister, serving twice in that role.

Rabin was a pioneer in his efforts to reconcile the so-called Palestinian problem, signing the 1994 Oslo Accords, an act which earned him the Nobel Peace Prize along with former political rival Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat, chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). Not everyone was jumping up and down; massive protests ensued.

Rabin was a symbol of peace or, depending on viewpoint, a dangerous traitor. In 1995, he was assassinated by a far-right extremist. Amos Gitai’s film “Rabin The Last Day,” which examines the event from the assassin’s stance, would serve as a good companion piece to this film.

The Rabin who emerges here is a man of integrity, consistency, loyalty and resilience. He has charm, wit, intelligence. But, most striking, he appears almost self-effacing, even shy and intensely private. Asked to define himself, he’s rattled. “Nothing is harder than defining yourself,” he says.

We learn that his family lived modestly and that “talking about money was a disgrace.” His relationship with his parents was complicated, his feelings for his taskmaster mother especially ambivalent. She died when he was still a youngster and he grew up quickly. He admired his father and they bonded unexpectedly when both were imprisoned in a British detention center. His lingering regret was that he did not get to say goodbye to his father on his deathbed.

Often it seems as though he’d rather not be discussing himself at all or taking credit for his career, suggesting that his professional trajectory was a fluke. He says, for example, that when Dayan was pulling together a band of resisters to fight the British extradition of Jews, he asked Rabin if he could drive a car. Not a car but a tractor, Rabin replied. With no fighting experience whatsoever he was hired on the spot and thus his journey to prime minister was launched.

But he was never casual about what was at stake or his unwavering commitment to justice. He understood the costs of both war and peace. He couldn’t understand why Jews would want to live on occupied territories at all, he said, since the land was so crappy. In addition he estimated that it cost the Israeli taxpayer more than $250,000 a year to protect each family there.

He saw the Palestinians as the inevitable victims of an apartheid that would only get worse. He ultimately came to the conclusion that giving up land was necessary while acknowledging that “peace is made with enemies, sometimes very cruel enemies.”

Looking back, he said that he offered the best chance for achieving peace. The comment is touching and unnerving in light of what followed. To Laufer’s credit, we do not see the assassination or its aftermath — its absence is a powerful presence and speaks volumes.

‘Sharon,’ by Dror Moreh

*

Demonized by many and viewed as a demagogue off the battlefield and an unforgiving, brutal warrior on the front lines, Ariel Sharon, born in 1928, served as the 11th prime minister of Israel for five turbulent years from 2001 to 2006. He was one of the country’s most contentious leaders, not least for his overseeing role in Israel’s catastrophic 1982 war with Lebanon when he was minister of defense.

Through much of his career, he was pegged as an inflexible Zionist whose mission was to grow the Jewish settlements in the Occupied Territories. On his way up — and, make no mistake, he had his sights set for decades on becoming prime minister. He felt that the expansion of the Jewish presence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip would be synonymous with security.

In Dror Moreh’s documentary, we’re told that Sharon had a lifelong terror of Arabs inculcated by his mother’s teachings. A gun was tucked under her pillow each night in the event an Arab broke into the house. Sharon said he himself would literally never turn his back on an Arab, including one who was among his closest friends for more than a quarter of a century. He said he liked a “dead terrorist” far more than a captured one.

Then abruptly in 2003, he reversed course, announcing the “Disengagement Plan,” and with the same aggressiveness that defined everything else he had done, he evicted dozens of Jewish settlers in the Gaza Strip and Northern Samaria, bulldozing their homes into piles of rubble. Under pressure from the Bush administration, which wanted to see a two-state solution and threatened to withhold arms if Sharon did not make concessions, he capitulated. Some leaders in the Arab world saw it as a manipulative tactic and that his unilateral move eliminated the possibility of negotiation.

We never learn if his change of heart represented an artful military strategy, an evolved political and moral vision, or a fear of inevitable failure. In the end, we wonder if being on the winning side was more important for him than anything else. Did it take precedence over principle? Who knows? At one point, he says very few people have to “make serious decisions or know the thrill of victory.” His feelings, his quest for power and glory, seem self-evident. Or do they? The mystery remains and it’s the centerpiece of Moreh’s film.

In this way, the Sharon documentary is similar to the one about Begin. Both explore enigmatic leaders who make unexplained 180-degree turns. Still, Sharon shows a level of depth that is regrettably absent in the documentary about Begin. He had an interest in art in general and Picasso in particular. We see him at a Picasso exhibit (not clear where), where he stares at each painting with fascination. He talks about his love of travel. He recounts nightmarish dreams.

Although they’re not mentioned in this film, he had a reputation for Falstaffian appetites that contributed to his substantial girth and, perhaps, also to his demise. Rumor has it that his car contained a small refrigerator, well stocked with caviar. It would have been a nice touch for the film to have mentioned this.

Still, like the other prime ministers, Sharon was very much alone. In 2006 he had a stroke, slipped into a coma and never fully recovered. He died eight years later. How odd in the end to compare him to Rabin, two leaders on the opposite ends of political spectrum. Yet the questions for both remain. What would have happened had their roles not been cut short — one by assassination, the other by a stroke?

In the end, these five documentaries screening on ChaiFlicks are well worth the effort. The leaders represented are a product of their eras, yet the battles they faced resonate today. This series couldn’t be timelier.