How come you’ve never heard of these Jewish artists?

This exhibition says it’s partly because they’re women

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

A small Jewish museum in the Bronx is seeking to rescue a group of mid-to-late-20th century artists from obscurity.

In their heyday, these artists were exhibited by top galleries in Paris, Milan and Manhattan alongside superstars like Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. They studied with renowned painters like the abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann. Many are represented in permanent collections at institutions like the Whitney and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Nevertheless, the 17 artists now on view at the Derfner Judaica Museum in a show called “Unlisted: Underappreciated Women Artists from the Permanent Collection,” are virtually unknown. But why? In part, the Derfner show suggests, because they’re women.

“I was aware we had these artists in our collection, and I was aware that a lot of them were women artists and were very under-known,” said Derfner’s associate curator, Emily O’Leary, who organized the show.

A hidden gem in the Bronx

The Derfner is part of the Hebrew Home at Riverdale, a nursing home and independent living facility overlooking the Hudson River. Its Judaica collection and art exhibitions are open to the public and deserve to be better known.

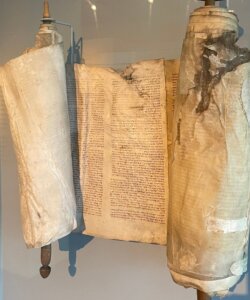

The museum was founded in 1982 by Ralph Baum, a German emigrant who collected Judaica as a way of salvaging European Jewish heritage after World War II. He and his wife Leuba gave more than 800 Jewish ceremonial objects to the Hebrew Home. In addition to staging exhibits like “Unlisted,” the Derfner has a selection of these objects on permanent display. They include a Torah that was partially burnt on Kristallnacht in Baum’s hometown, and a kiddush cup and spice box that were buried in Norway to hide them from the Nazis.

‘Unlisted’ and underappreciated

The title of the “Unlisted” show is a play on the term “listed.” In the art world, “listed” confers legitimacy by indicating that artists can be found in standard reference works and museum collections. While many of these women were, in fact, “listed,” the museum’s printed introduction to the show suggests that their obscurity underscores the “arbitrariness of the art world” and the ways in which women artists “had to compete in a sexist, male-dominated” field while juggling traditional gender roles.

Artist Shirley Roman, for example, belonged to the Graphic Eye artists’ collective and gallery in Port Washington, New York. The gallery’s location in a suburban Long Island town was crucial for local women who otherwise “didn’t have the time to run to New York for their art and get back home in time to cook dinner for the family,” another Graphic Eye artist, Lois Polansky, told The New York Times in an article cited by the Derfner.

Some artists simply vanished

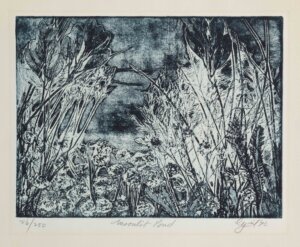

Artist Ruth Cyril is represented at the Derfner by an etching, “Moonlit Pond.” Her work can also be found at the Victoria and Albert in London, the Hirshhorn and National Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the Met in New York. Yet at some point in her career, Cyril simply vanished. The place and date of her death are unknown. (Some museums list it as 1988, but a definitive account of Atelier 17, a printmaking studio where Cyril worked, says that is incorrect.)

Suzanne Rodillon, who had a solo show in 1957 at an important Milan gallery patronized by Peggy Guggenheim, abruptly closed her studio in 1966 “and walked away, never to paint again,” O’Leary said. “No idea why. I’ve researched her, found lots of exhibition announcements from newspapers, and she does have an artist’s file at the Museum of Modern Art, but there wasn’t a lot in it.”

Postwar embrace of Jewish themes

Thirteen of the 17 artists in the show are Jewish. Many of them, like Terry Haass, were immigrants. Haass moved to Paris from Czechoslovakia to escape the Nazis, then fled to New York when Germany invaded France. The Derfner is showing her abstract etching “Meteors,” with black trails and bursts of white light on an orange background.

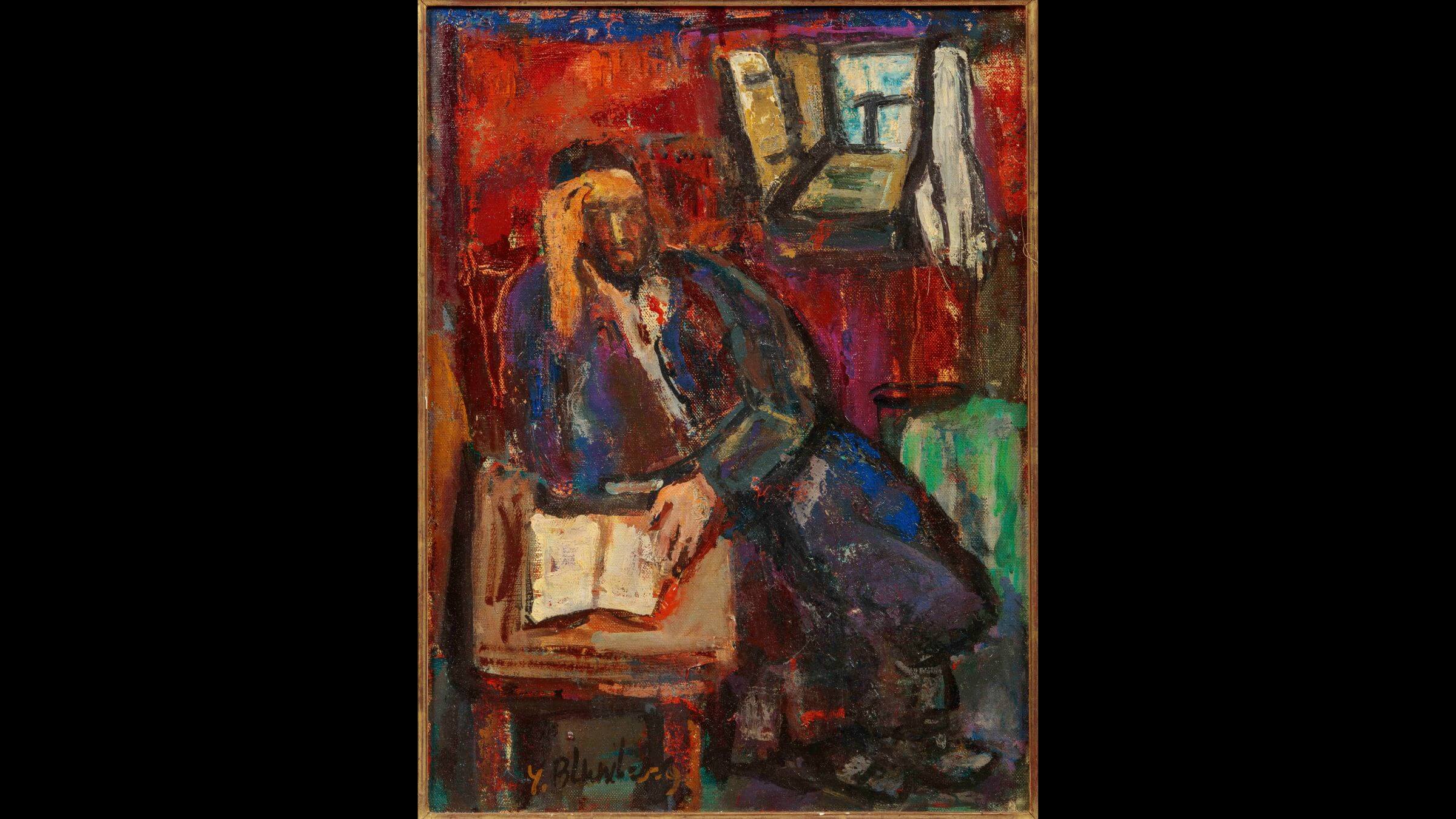

“Unlisted” includes two figurative paintings with explicitly Jewish subjects. “Scholar in His Study” is a colorful postwar portrait of a man in a skullcap with an open book by Yuli Blumberg. Born in what is now Lithuania, Blumberg was an established artist in Europe before coming to the U.S., having shown alongside the renowned expressionist Oskar Kokoschka. Blumberg was quoted in 1946 as saying that her work reflected her “imperfect grasp of a shattering vision.”

“The Law Giver,” by Hungarian immigrant Margit Beck, is a modernist portrait of a bearded Moses-like figure wearing a tallit and skullcap, holding a tablet. The image is rendered in vertical strips, his misaligned eyes underscoring a sorrowful expression.

The painting exemplifies a “post-Holocaust, postwar embrace of Jewish themes,” said the Derfner’s chief curator, Susan Chevlowe. “The Moses figure was really popular among Jewish artists in this period. It showed this resilience, this presence, this continuity and tradition, and the idea that the people and the religion would survive.”

“Unlisted: Underappreciated Women Artists from the Permanent Collection” can be seen through Oct. 2 at the Derfner Judaica Museum, 5901 Palisade Ave., the Bronx, New York, Sunday-Thursday, 10:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Visitors must bring photo ID, proof of COVID-19 vaccination and a mask.