‘Mazel tov on assimilating:’ The strange, rich history of Rosh Hashanah advertisements

In the postwar years, as the American Jewish community underwent dramatic changes, Rosh Hashanah greetings became a surprising marketing trend

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

“Nobody can chide you for forgetting them — if Your Greeting is published in the Annual Rosh Hashanah Edition,” declared a 1937 issue of The American Jewish World of Minnesota.

Long before the era of perfectly-staged social media posts wishing friends and family “l’shanah tovah,” families and companies placed Rosh Hashanah greetings in newspapers, a practice that originated in the early 1900s as a revenue generator for American Jewish periodicals.

Holiday greetings gained steam as a popular way for public figures and institutions to connect with their constituencies in 1927, when President Calvin Coolidge issued the first official presidential Christmas greeting. The tradition quickly expanded to a variety of holidays, with prominent politicians, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, placing ads in Jewish newspapers before the High Holidays.

By the late 1940s, more local businesses and national brands had caught onto the trend, and began placing holiday greetings in Jewish publications as a way to engage with and show support for the Jewish community. The lengths to which advertisers went to court the Jewish market were unparalleled. The greetings were specific, personal and highly creative — in contrast to, say, the subjects and imagery used by advertisers at Christmastime, which involved “pretty generic Christian content,” said Leigh Eric Schmidt, author of “Consumer Rites: The Buying and Selling of American Holidays.”

The following six Rosh Hashanah greetings offer a glimpse of the changing place of Jews in the postwar American landscape — a time when the Jewish community underwent accelerated assimilation but, as these ads show, stayed beautifully unique.

Even though the St. Paul Dispatch-Pioneer Press, a secular newspaper serving Minneapolis’ Twin Cities, struggled to spell “Israel” — see “Isreal” — the paper recognized the significance of the new country for the American Jewish community in this greeting placed in the Minnesota-based American Jewish World in 1948.

The advertisement wished “the infant state and its people everywhere a New Year overflowing with peace, prosperity, and happiness.”

By acknowledging the new state of Israel in such affectionate language — talking about it in the same way one might speak to a parent about a beloved new child — the ad sought to tug on the heartstrings of the Jewish community, and affirmed the special interest advertisers were beginning to take in building a relationship with it.

Maxwell House’s 1953 ad in the Los Angeles-based B’nai B’rith Messenger, which quoted from the prophet Amos, demonstrated the astonishing degree of thought advertisers put into appealing to the Jewish market. It was during this period that Maxwell House inaugurated a series of greetings highlighting obscure books from the Tanakh, including Ezra in 1967 and Samuel in 1970.

Most U.S. Jews, then as now, likely weren’t particularly familiar with Amos, Ezra and Samuel, making Maxwell House’s choice to highlight them fairly remarkable. The campaign, conceived by a firm run by Joseph Jacobs — an ad maven who had gotten his start at the Forward — was planned as a way for the coffee company to brand itself “as the ‘taste of tradition’ for Jews,” said Kerri P. Steinberg, author of “Jewish Mad Men: Advertising and the Design of the American Jewish Experience.” That work, Steinberg said, was part of a broader mission for Jacobs, who aspired “to inform the mainstream marketplace of the purchasing power of American Jews.”

This greeting from Mildred Younger, a California politician then running for the state senate, was placed in the B’nai B’rith Messenger in 1954. It was unusual to come across a Rosh Hashanah greeting from a female politician at the time. That the Republican Younger, who would go on to lose her bid to become the first woman in the California senate, placed a greeting in the paper spoke to the growing political significance of the Jewish community.

This ad, placed in The American Jewish World in 1964 by a local chemical plant, which would a few years later be declared a Superfund site, explicitly stated the implication of many Rosh Hashanah greetings from the time. “One of the best examples of assimilation into community has been set by those of the Jewish persuasion,” the ad said. “While retaining their individuality, they have become a contributing force to their communities.”

“Jews, like other Americans… had the opportunity to leave behind ethnic ties… and redefine themselves according to the then popular American melting pot theory,” as they moved to suburbia, Steinberg wrote in “Jewish Mad Men.” For her, the first two lines of this greeting “echoed what so many Jews wanted to hear about themselves at this time” — that they had “made it” in America. This greeting went further than that, publicly wishing Jews “mazel tov on assimilating!”

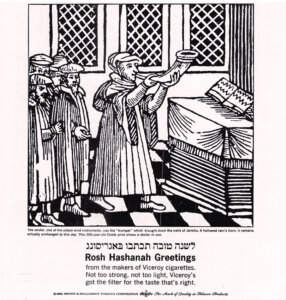

The Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation dug into the archives of Jewish history to find a 300-year-old Dutch woodcut illustration of a shofar blower for this greeting, placed in The Sentinel, a Chicago Jewish newspaper, in 1965.

The ad also includes the phase “Rosh Hashanah Greetings” in Yiddish, a language that was a bit unusual to find in an English-language paper in 1965. According to Steinberg, the use of the Yiddish phrase “underscored the traditional value or the legitimacy of the illustration” and would have helped it appeal to an aging readership.

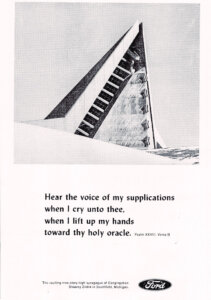

This 1965 Rosh Hashanah greeting from Ford quoted from the Book of Psalms: “Hear the voice of my supplications… when I lift up my hands toward thy holy oracle.” Previous Rosh Hashanah greetings from the automobile company had included a quote from a popular High Holiday prayer book by Rabbi Morris Silverman in one year, and an excerpt from the priestly blessings another.

The greeting included a photo of a newly built Conservative synagogue in Southfield, Michigan, Congregation Shaarey Zedek, which was completed in 1962. The modern synagogue architecture depicted, Steinberg said, was likely incorporated in the ad to appeal to the younger generation of Jews, while the quote from Psalms was probably intended to draw older, more traditional generations.

The overall effect spoke to the changing setting of American Jewish life: The quote, combined with the picturesque new “holy” Michigan locale, suggested that Jewish religious life could thrive in American suburbs.

These Rosh Hashanah ads don’t just celebrate the rapid changes in the midcentury Jewish community and its growing role as a powerful American consumer. They also, most fundamentally, served to greet the Jewish community as newly and remarkably American.