This notorious artist fought trauma, antisemitism and his own worst instincts — Lucian Freud at 100

An ex-lover called Sigmund Freud’s grandson, who fathered more than a dozen children, ‘an evil man’

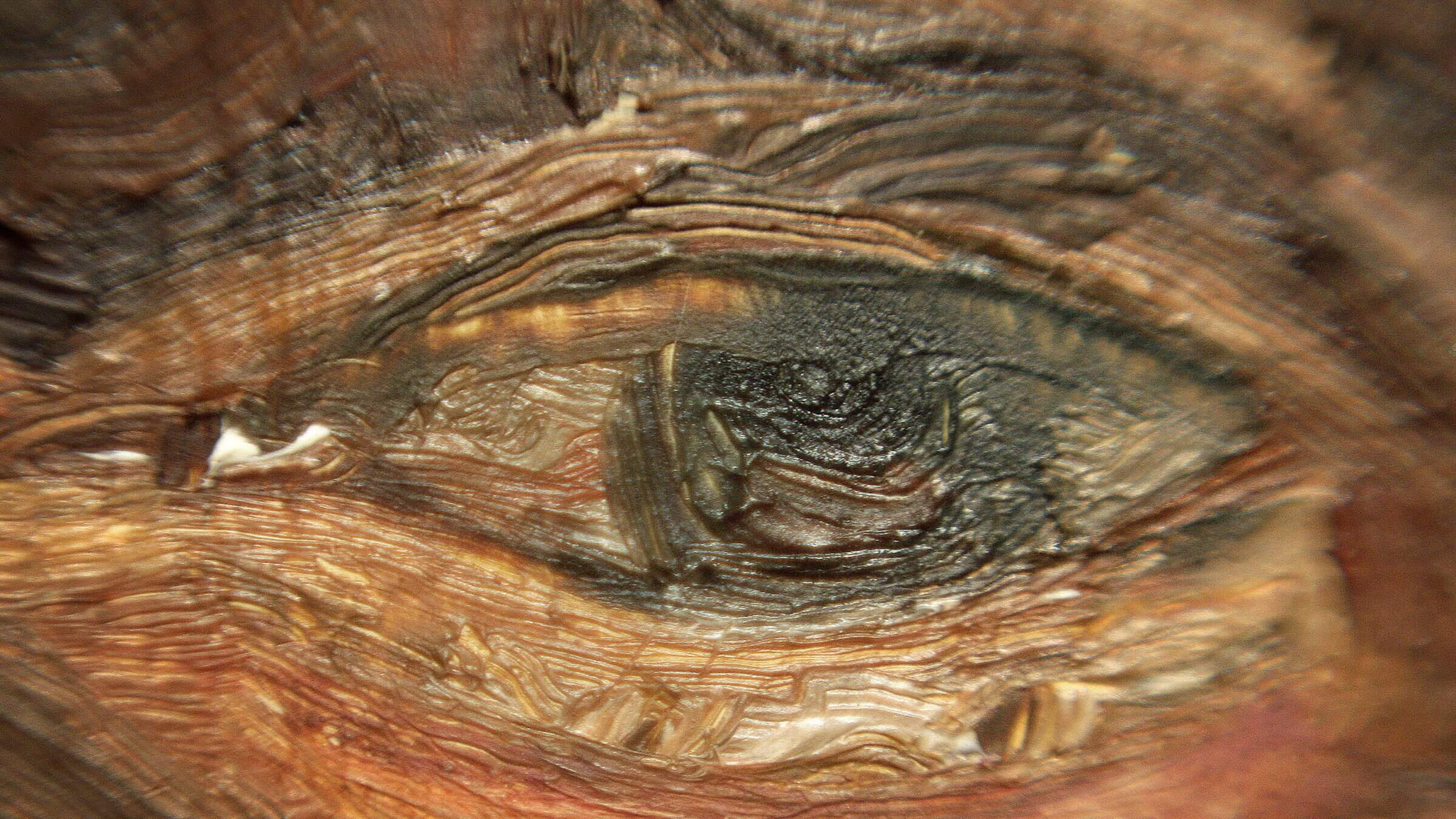

Self-Portrait with a Black Eye by Lucian Freud. Photo by Getty Images

Three years ago, Rishi Sunak, now Britain’s prime minister, spoke during a parliamentary debate in London about the “Contribution of the Jewish Community to the U.K.,” specifically lauding the English Jewish painter Lucian Freud among overachievers.

Although widely accepted as a major modern realist whose works regularly sell for millions, Freud, whose centenary is on Dec. 8, did not always inspire personal enthusiasm, even among his intimate friends. The poet Stephen Spender, of German Jewish origin, with whom young Freud had a romantic affair, a new collection of letters documents, is a case in point. Feelings cooled, and decades later, when both attended the traditional Jewish wedding ceremony for the painter R.B. Kitaj, Spender confided to a fellow guest: “I can’t stand being in the same place with Lucian. He is an evil man.”

Freud, grandson of the founder of psychoanalysis and son of a prosperous architect, routinely treated people badly. He shunned his doting Jewish mother, Lucie Brasch, as suffocating. Yet in the 1970s, when she suffered brain damage following a suicide attempt after his father’s death, Freud became tolerant of her presence as a mute, passive figure. As such, she posed for an estimated 4000 hours for a series of portraits which, considered among his finest works, reflected vital skin tones like great portraitists of the past such as Rubens. Even his mother’s death in 1989 did not lessen his urge to depict her. Freud demanded permission of the hospital where she died to draw a charcoal deathbed portrait.

Freud also painted far less dignified nudes of friends, and even of his children. He acknowledged fathering 14 children, although some biographers claim the true number may be closer to 40. So frantic was his intimate life that in 1961, three of his children were born to three different women.

Some biographers have asserted that his behaving like a Jewish Don Giovanni may have been a delayed response to the trauma caused when his prominent family fled their Berlin home after the Nazis arrived to power. Freud claimed that, as a small boy in 1929, he was already impacted by increasing antisemitism in Berlin, and he reacted to sudden outsider status in schoolyards by rebelling resentfully against the new strictures.

Relocating to the U.K. by 1933, five years before grandfather Sigmund could be persuaded to escape from Nazi Austria, Freud and his parents were nationalized as English by 1939 through indirect acquaintanceship with British royals. The resulting special influence permitted them to avoid internment as enemy aliens, which was the routine fate of less well-connected refugees.

In his adopted land, Freud encountered different types of antisemitism, as he later noted, explaining that as an emigre youngster, “I was not very conscious of being Jewish but I was conscious of antisemitism.” In Paddington, where his family resided, people would complain about Jews, referring to them as “saucepans” in Cockney rhyming slang — the full term, “saucepan lids,” was intended to rhyme with the unspoken slur of “Yids.” Freud demurred to classmates: “Now, none of that. I am a saucepan.”

Despite his own saucepan status, Freud never abandoned his disdain, shared by some assimilated German Jews of a certain era, for Eastern European Jews. Still, as an adult, he formed lasting ties with fellow Jewish artists such as Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff and Kitaj. Auerbach became his closest painter friend and adviser.

Auerbach, still active today at age 91, lacked the material advantages of Freud and emigrated to the U.K. alone, rather than in a well-funded family group, as part of the Kindertransport, which brought Jewish children to Britain to escape Nazi persecution. Auerbach’s parents remained behind in Germany and were murdered at Auschwitz. According to Auerbach, Freud once confessed that his mother’s devotion to him as her favorite child made it “impossible for [Freud] to have so unconditional a relationship with any other woman.”

Nevertheless he tried. In the 1940s, he married Kitty Epstein, daughter of the prominent English Jewish sculptor Jacob Epstein. Typically, Freud’s portraits of his spouse were given anonymous titles such as Girl with a Kitten (1947), Girl with Roses (1948), and Girl with a White Dog (1951-1952) instead of humanizing her with a name or specified personal affiliation.

In the early 1950s, when Freud married his second wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood, daughter of the noblewoman Maureen Guinness, he attracted the ire of some U.K. snobs. The author Evelyn Waugh wrote to a friend: “Poor Maureen’s daughter made a runaway match with a terrible Yid.” Randolph Churchill, Winston’s son, once exclaimed upon seeing Freud arrive at his mother-in-law’s home: “What the bloody hell is Maureen doing, turning her house into a bloody synagogue?” Indeed, Freud’s mother-in-law was scarcely more tolerant, introducing him to friends as “Lucian Fraud,” and the marriage did not last.

The portraits continued, though, including one of the English Jewish painter Timothy Behrens, seen in Red Haired Man on a Chair (1962). Behrens adopted a contorted pose as part of a cruciform composition, possibly an ironic allusion to the Yiddishkeit in their shaded backgrounds. Other Jews who sat for Freud portraits included Jacob Rothschild, who became a longtime friend, and an unnamed art collector who commuted from New York once monthly for commissioned sittings, during which Freud took the opportunity to avidly discuss Jewish ritual and belief.

Other commissions ended less harmoniously. After the German Jewish antiquarian book dealer Bernard Breslauer died in 2004, it was discovered that Breslauer had so disliked the way Freud’s portrait accentuated his double chin that he destroyed the painting, much to the artist’s dismay.

Other potential Jewish clients rejected even the thought of the notorious Lothario Freud getting anywhere near their offspring. James Goldsmith, the financier of Jewish origin, once wrote Freud to warn him that if he dared try to paint his daughter, “he’d have [Freud] murdered.” Whereupon Freud asked flippantly, “Is that a commission?”

And Freud’s lawyer Arnold Abraham Goodman, who sat in the House of Lords, nixed the possibility of Freud ever painting the portrait of Diana, Princess of Wales by declaring: “I wouldn’t leave her in the room with Lucian.”

Wary for an entire lifetime after his early experiences fleeing Fascist Europe, for decades Freud mostly refused to allow exhibits of his artworks in Germany or Austria. In 1989 he sardonically observed that the “best thing about Germany was the Berlin Wall.” Freud feared a reunified and strengthened Germany, just as he excoriated Austria for its treatment of his family. Four of his elderly great-aunts, sisters of Sigmund Freud, had been murdered in concentration camps. Only after his death in 2011 did a major show of his work open in Vienna.

As if a certain amorality was a natural response to his early angst, Freud became fascinated by Jewish nogoodniks like disgraced media proprietor Robert Maxwell. Today’s Jewish figurative painters such as Eric Fischl may have absorbed some of Freud’s approach to portraiture, yet without the tormented mixture of feistiness and using modern Jewish history as an excuse for personal misbehavior, as Freud did so notoriously.