Why it can seem easier to weep for Don Quixote than your own father

In ‘Still No Word From You,’ Peter Orner offers a heartfelt memoir in books and marginalia

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

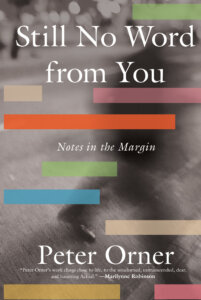

Still No Word from You: Notes in the Margin

By Peter Orner

Catapult, 320 pages, $26

In Peter Orner’s Still No Word from You, literature and life are inextricably intertwined, each illuminating the other. Orner’s latest collection is part memoir, part criticism, transcending genre, or attempting to. Its essays are now chapters, some no more than a paragraph long — ruminations on evanescence and permanence, ineffability and communication, and the grip of the past on the present.

Orner is director of creative writing at Dartmouth College and the author of an earlier essay collection, Am I Alone Here? that was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. He also has written several novels and short-story collections. This was my first encounter with him.

The subtitle of Orner’s previous essay collection seems to define his literary project: “Notes on Living to Read and Reading to Live.” Books are essential nourishment to him. He is “feeding off other people’s words,” he confesses in the new collection. Its subtitle, Notes in the Margin, analogizes his musings to marginalia, jottings representing the intersection of authorial intention and readerly sensibility.

Still No Word from You is divided into six sections, beginning with “Morning” and ending with “Night.” The organization suggests a parallel between the passage of a day and a human lifespan. But the stories Orner recounts — of parents, grandparents, wives, friends and others — are not arranged in a straightforward chronology. It is not always, or often, clear why a particular essay lands where it does. Beneath the gesture toward coherence are elements of randomness.

The book’s nonlinearity and Orner’s intense saturation in world literature may limit his audience. But his simple, direct prose style renders Still No Word from You surprisingly accessible. His short, clear sentences and the brevity of each chapter make the book read quickly and easily, even as it almost demands rereading.

The book’s first essay pairs an image of Orner’s mother scrubbing dishes in a house that no longer exists with a television picture of Richard Nixon’s helicopter taking off from the White House after his 1974 resignation. Something in his mother’s eyes, Orner writes, suggests that she, too, has taken off. Most of the book’s revelations are similarly subtle.

The memory of being disinherited by his father evokes an Amy Clampitt poem, “The Prairie,” referencing a Jew in a Chekhov story burning his inheritance. “The Prairie,” Orner writes, is “ultimately about the stories we carry across the generations, not the money that does — or doesn’t — get passed on.”

In another essay, Orner recalls his family confined to a round kitchen table, his angry father, “a little tomato-faced volcano in a three-piece suit,” impossible to escape. “We’re still wedged in there because there’s no greater fantasy on the face of the earth than the linearity of time,” he writes. “Time only circles … The house is gone, flattened, bulldozed, and we’re still trying to make it through dinner.”

Along with painful family memories, Orner finds himself engaged by a sort of literary metaverse: writers writing about other writers. He interrogates Hermione Lee’s description of Virginia Woolf’s suicide by drowning, suggesting it is too passive. He also admits to being more moved at times by literature than by life, to weeping at Don Quixote’s death but not his father’s. (His father is nevertheless this volume’s most persistent ghost.)

Orner’s range of literary references, helpfully listed at the end of the book, is wide. Analyzing Arthur Miller’s iconic play, Death of a Salesman, he decides that its subject is “the confusions of a fundamentally sapped human being.” He is equally riveted by echoes of the past in Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table and Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo. Orner’s appetite for poetry is especially keen, encompassing Pablo Neruda (“He tries, like us all, to conjure what’s gone with words …”), Paul Celan, Rita Dove and Robert Lowell, among others.

Amid all this literary erudition, the book’s title is both ironic and apt. It borrows a haunting line from a letter sent by Orner’s paternal grandfather to his wife from the Pacific theater during World War II: “Another day and still no word from you.” He wrote her daily, Orner tells us, and the letters survived. She must have valued them. But it seems that she scarcely bothered to reply. That silence reflected or prefigured a coldness that eventually led them, after their reunion, to separate beds.

Orner is touched by writers who were never celebrated or have faded from view, like Wright Morris, a mid-20th-century novelist, essayist and photographer. Of Morris’ novel Plains Song, Orner writes: “In this book certain moments last pages. Other times, the years pass in half a sentence. Major characters suddenly become minor. People die mid-paragraph. Isn’t this how it happens? Blink and you’re forgotten.”

Orner seeks comfort in the notion that past and present can’t be pried apart, a philosophy he infers from a Yaakov Shabtai novel, Past Continuous.

In other essays, Orner describes visitations with his own dead, in a Fall River, Massachusetts, cemetery and elsewhere. They remain vibrant to him, the magical realist foundation of memoir. Otherwise, wouldn’t death be even more unbearable? “What’s happened,” Orner concludes, “has happened and yet, always, it will keep happening.”