He was one of our greatest writers — so, why don’t people talk about him anymore?

A new book tries to reclaim the legacy of I.L. Peretz

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

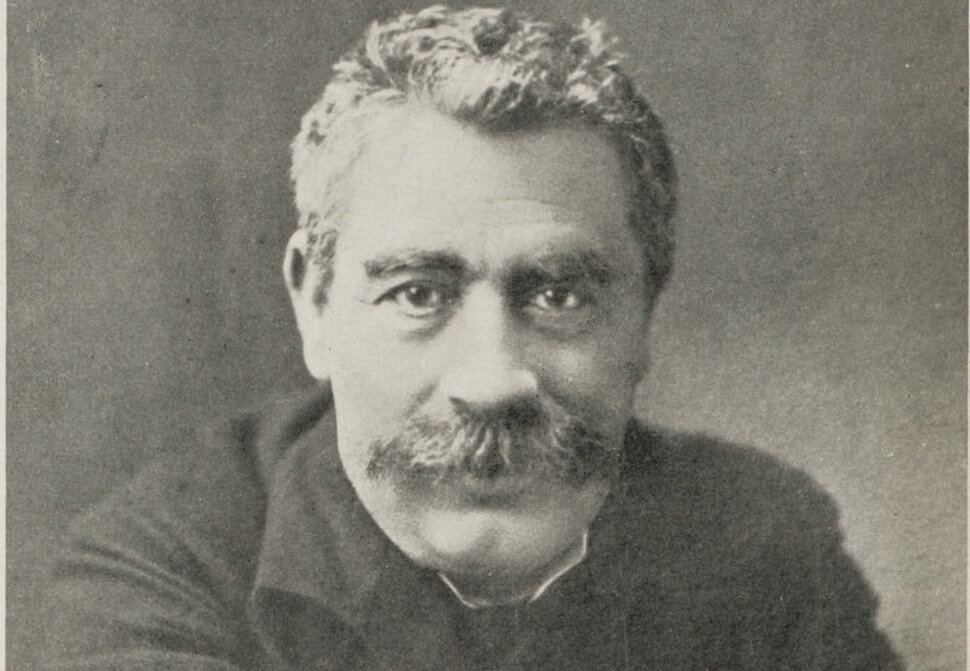

The literary historian Ruth Wisse once asserted that except for Theodor Herzl, “no Jewish writer had a more direct effect on modern Jewry” than I. L. Peretz (1852-1915). Admired for his socially progressive fiction as well as neoromantic folklore-like Hasidic tales, Peretz is acclaimed in a new book, The Radical Isaac. Its author, Adi Mahalel, who teaches Yiddish studies at the University of Maryland, has contributed to the Yiddish Forverts, and translated Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Hanan Ayalti and Yosl Birshteyn, as well as poetry by Yankev Glatshteyn for the Yiddish punk band Koyt Far Dayn Fardakht (The Filth of Your Suspicion). I spoke with Mahalel spoke about Peretz’s inner complexities and unexpected messages.

Can Peretz be compared to Martin Buber, whose narratives about Hasidim were criticized for being poetic evocations rather than ethnographically accurate depictions? Buber’s Hasidim were said to be unlike historical or current Hasidim; is it fair to say the same of Peretz’s Hasidim, despite the psychological, social and spiritual force that they express?

It’s extremely fair; very, very fair because Buber himself was influenced by Peretz’s Hasidic stories, so the link that you make is relevant. I don’t think Peretz or Buber used the Hasidic material to promote the Hasidic movement as the original folk tales were intended to do. Instead, Peretz was promoting Jewish socialism. Peretz reinvented Hasidism as a working-class effort caring for simple Jews.

In Zamość, southeastern Poland, Peretz established a night school for workers, teaching reading and Jewish history, that was shut down by authorities after local Hasidim complained that it was “socialistic.” Were the Hasidim whom Peretz described in exalted folkloric terms his ideological enemies?

The actual Hasidim, absolutely. Peretz promoted modern Yiddish culture in a progressive agenda for workers, so those interested in promoting a Hasidic way of life were opposed to him. As part of his writing after the Jewish Enlightenment, Peretz embraced Hasidism, which was the biggest enemy of the Jewish Enlightenment.

In Peretz’s 1894 tale “Bontshe Shvayg” (1894), the silent laboring protagonist has endless misfortunes: “His circumcision was botched by a bungler … who couldn’t even staunch the blood.” Was this detail of mutilation, anticipating the musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch about a glam rocker whose sex-change operation goes wrong, offered in contrast to Peretz’s own phallic triumphs as a Yiddish Don Juan and ladies’ man?

In memoirs about his life, there are anecdotes about Peretz going with women, it’s true. Being incapable sexually is part of Bontshe’s powerlessness as a worker. That’s how sexual and proletarian imagery are woven together in the story.

You describe Peretz as slightly more feminist than other Jewish male writers of his generation, with such short stories as “The Anger of a Jewish Woman” evoking the misery of a balabusta with a worthless husband. Yet didn’t Peretz physically abuse his first wife by tearing the sheitel off her head during a domestic quarrel and hurling it into the fireplace? That isn’t the act of a feminist, right?

You’re not wrong. He’s maybe a step beyond other writers, but Peretz didn’t make major headway in feminism. Peretz had genuine interest in promoting women as part of the oppressed classes but didn’t grasp feminism in sufficient depth, nothing near what feminism is supposed to look like today. Although Peretz is a figure to look up to and learn from as an involved intellectual prominent in Ashkenazi life, we shouldn’t glorify and idealize everything about him.

Fans of Peretz sometimes bemoan that he is less famous today than Sholem Aleichem, who benefits from the celebrity of Fiddler on the Roof. Are any of Peretz’s characters suitable for musical adaptation? Will there ever be a Fiddler for Peretz?

That’s a great question, Even when characters by Peretz were included in an off-Broadway play in the 1950s, they were sandwiched in a show called The World of Sholem Aleichem. His wrote plays, but they are rarely, if ever, staged. They’re more for reading than actual performance.

You argue that critics have typically described Peretz as becoming disenchanted with socialism, but Bontshe Shvayg fits into a lifelong pattern of primarily championing downtrodden workers, rather than Jews per se. Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Gimpel the Fool” parodied Peretz’s text by arguing the good aspects of passivity. Did Singer show any signs of social consciousness, like Peretz?

Gimpel the Fool is the opposite of Bontshe, showing no interest in workers, social struggle, or collectively based accomplishments; in fact, Gimpel promotes entrepreneurship in a clear response to “Bontshe” as a form of ideological debate. Singer was always a staunch conservative and opponent of any kind of progressivism. He was not only anti-Communist, but anti-Socialist, and in America, a Republican; Singer even had some affinities with McCarthyism.

Peretz believed in the possibility of Jewish culture thriving in Poland, and in 1894 he rejected the essayist Ahad Ha’am’s identification of a “spiritual center” for Jews in the land of Israel, asking how a center could be so far from where most people live. Was Peretz overoptimistic in this sense?

From a certain perspective, I don’t think he was overoptimistic. Jews did thrive in Poland between the two world wars and there was Jewish culture. Of course antisemitism was also very strong, but the eventual destruction came from outside Poland. I’m not overlooking Polish antisemitism, but most of the crime came from the West. Part of progressivism is intertwined with optimism. You can’t be a progressive without a sense of optimism, a sense of there being a pathway forward. Judging Peretz from a post-World War II point of view is unfair; who could have fathomed such horrors?

In a brief 1894 article, “Passover is Coming,” Peretz inverts Jewish tradition by urging readers to forget about the holiday because “I don’t even want to say ‘next year in Jerusalem!'”(L’Shana Haba’ah B’Yerushalayim) because “people don’t become pregnant merely from speaking,” (Fun zogn, vert men nisht trogn), the latter a Yiddish maxim dating back at least as far as Reb Nachman of Bratslav. Did Peretz intend to mock the uselessness of Jews who merely expressed good intentions, as opposed to those devoted to progressive action?

I think it’s a statement of progressive action. Peretz is addressing readers with some Jewish background in a way they can understand, by referring to texts that every Jew was presumed to know, to lead them towards principles of social progressivism. I don’t think he’s making fun of Jews or Jewish traditions. He just uses it as rich material, a well of images and themes, and I think he thrives on it. It’s one of my favorite texts by Peretz, amusing and punchy. He’s not doing it in any way from a cynical perspective. He belongs to this Jewish culture. He was secular, but Jewish culture was prominent in his life. I couldn’t find any source that said he had a mezuzah on the door to his apartment, but I would say it’s 99% sure. He was unapologetically intertwined with Jewish culture, but wanted to weave it with progressivism. That was his diaspora viewpoint.