When Harry Belafonte said the Jewish blessing for bread with Zero Mostel

The actor, singer and civil rights icon starred in 1970’s ‘The Angel Levine’

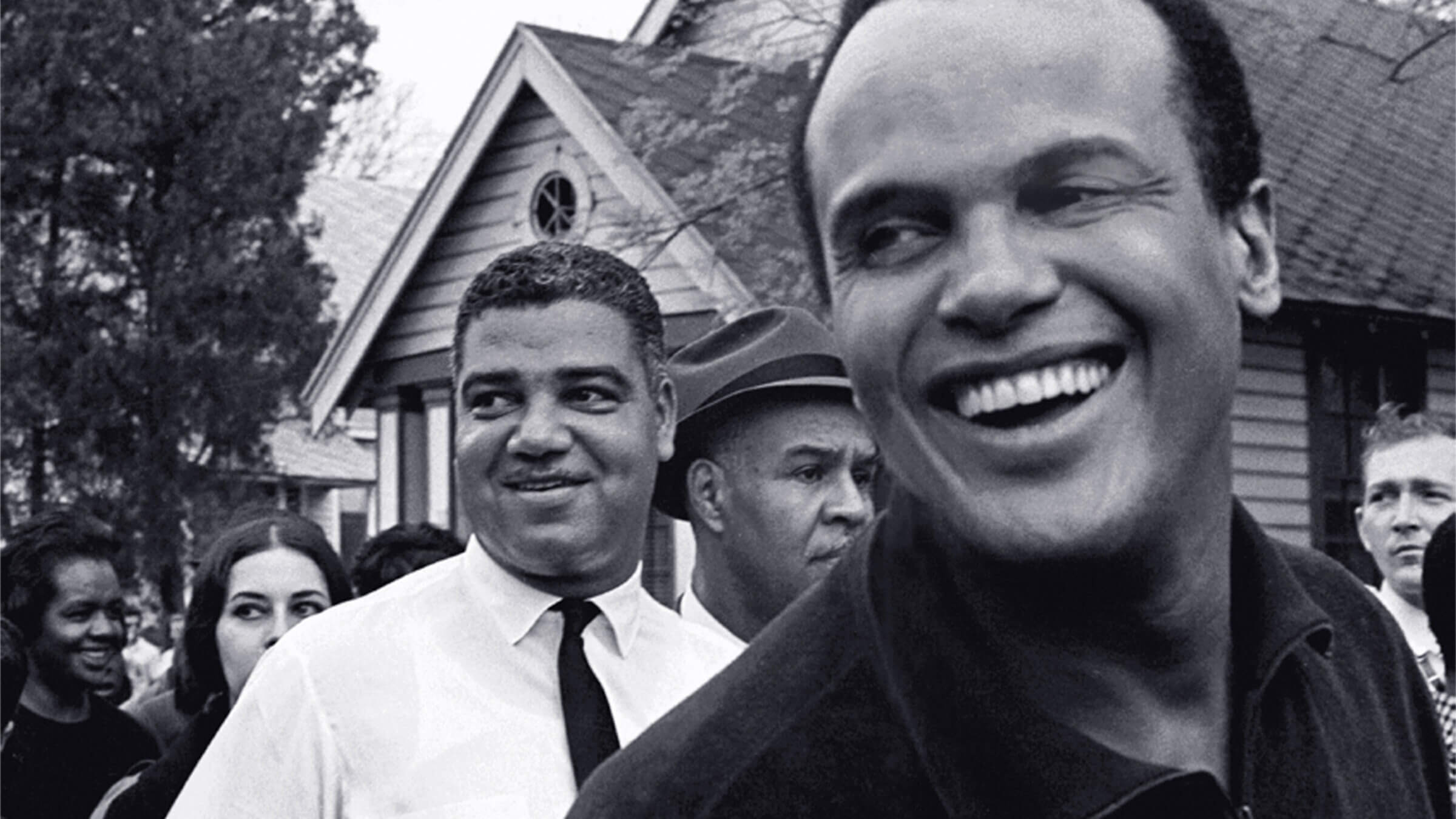

Harry Belafonte in 1971. Photo by Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images

Harry Belafonte, the singer, actor and civil rights icon, is now with the angels. He once played one.

Belafonte, who died Tuesday at age 96, starred in an oft-forgotten 1970 film, The Angel Levine, based on a short story by Bernard Malamud. Belafonte plays the titular angel, Alexander Levine, who is on work probation until he can successfully help a Jewish tailor, Zero Mostel’s Morris Mishkin, who is attending to his sick wife and has an application out for welfare.

Discovering Levine in his kitchen, Mishkin at first fears he’s being robbed. Then, when he hears Levine give his name, he wonders if he’s Jewish.

“All my life,” Levine answers, “willingly.” To prove it, he puts on his hat and flawlessly recites hamotzi, the Hebrew blessing over bread. (Levine and Mishkin later nosh on matzo brei.)

Mishkin comes to believe Levine’s Jewishness, but doubts if he is in fact an angel. This proves a conundrum for Levine, who needs to get the people of Earth to believe he’s who he says he is in order to earn his wings. This frustration over being questioned is one many Jews of color may identify with and, to the film’s credit, it shows a local Ethiopian synagogue just before the credits, a rare big-screen acknowledgment of Black Jews, and proof it’s not just playing the concept for laughs.

In reality, Belafonte was raised Catholic, though his paternal grandfather was, as he wrote in My Song: A Memoir, “a white Dutch Jew who drifted over to the islands after chasing gold and diamonds, with no luck at all.” Belafonte’s second wife, Julie Robinson, was also Jewish.

In My Song, Belafonte said he was drawn to The Angel Levine as a story of race relations, and that Mostel’s character reminded him of a Jewish tailor “who’d let my mother buy those sun-bleached suits in his store window at a generous discount, then taught her how to dye them blue.”

The film, like much of Belafonte’s offscreen work for social justice, had a mixed coalition, scripted by Black writer Bill Gunn and white writer Ronald Ribman and directed by Slovak Academy Award-winner Ján Kadár. At the film’s core is a humanist message that Belafonte exemplified.

When Levine asks Mishkin why he was talking with a policeman, he admits he thought of turning the angel in (he would have a case for breaking and entering). He didn’t though.

“Why should one Jew turn in another Jew?” Mishkin says.

“And if I wasn’t Jewish?” Levine asks.

Mishkin, still unsure of the angelic nature of his guest, answers: “Still, you’d be a person.”

As the film draws to a close, Levine fears he won’t be remembered, that his deeds on Earth haven’t been enough to join the world to come. But the actor who played him, along with his many strides for civil rights, won’t soon be forgotten.