‘Isn’t it rich’ — Sondheim, Buñuel, and the discreet charm of the bourgeois audience they couldn’t live without

Stephen Sondheim’s final musical, ‘Here We Are,’ tackles two of the great surrealist films of the 20th century

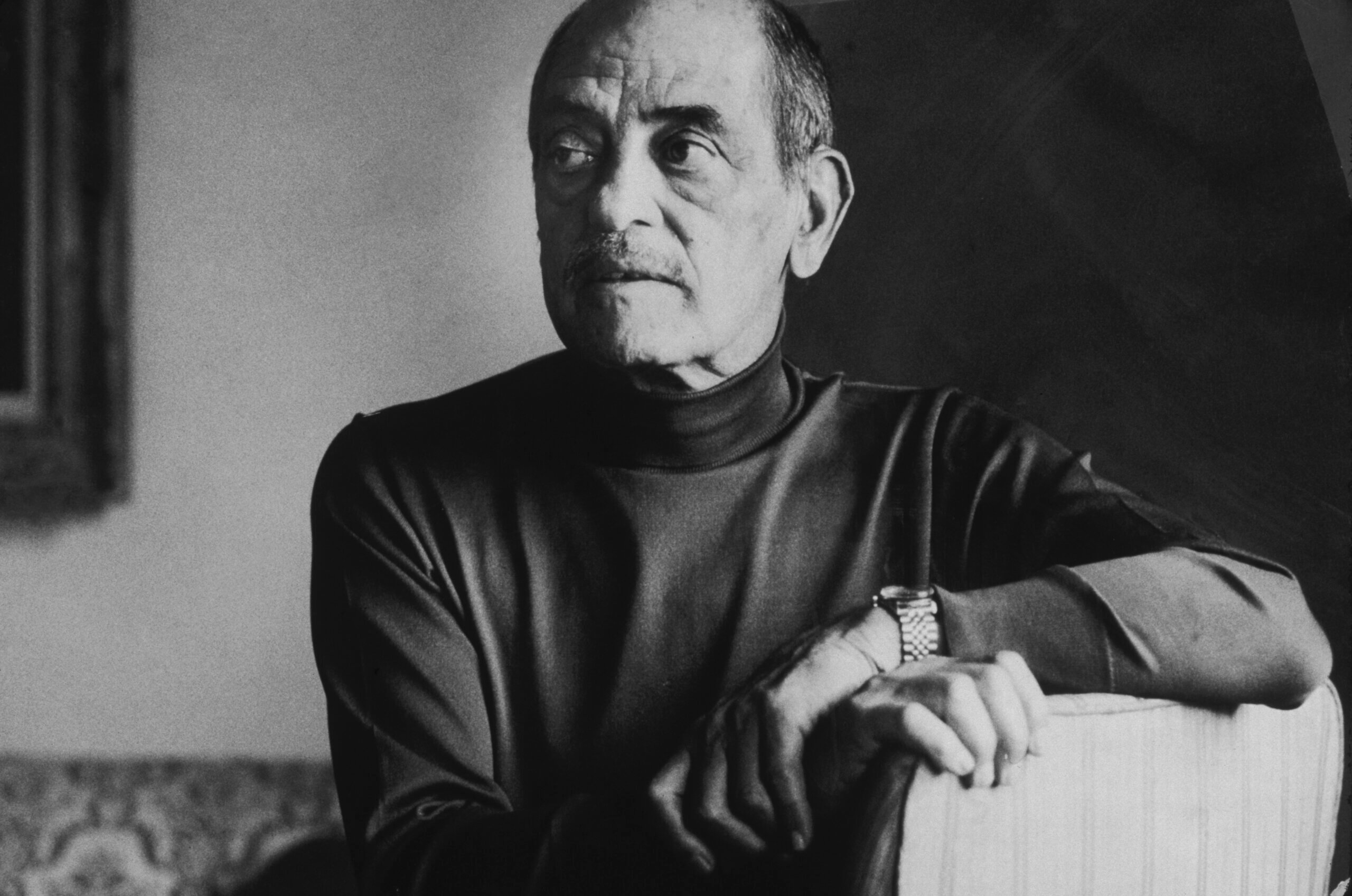

Luis Buñuel, one of the great surrealist directors of the 20th century, transgressed social boundaries — including in one film, made with Salvador Dalí, that featured a shot of a man slicing a woman’s eyeball. Graphic by Anya Ulinich

A group of friends arrives at a luxurious villa. There, the friction between them escalates, and they experience something of the surreality of any life lived in relation to others. They fight, engage in covert trysts and try to maintain a veneer of politeness. At some point, someone dies. In the end, the survivors remain the static, strange creatures they always were. Their actions change their circumstances, but also confirm their vanity. Even under extraordinary pressure, people rarely change.

This is the plot, minus some meaningful complications, of the dissident surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel’s landmark movies The Exterminating Angel (1962) and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972).

It’s also the setup of the Stephen Sondheim musical A Little Night Music — itself an adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s 1955 film Smiles of a Summer Night — which premiered on Broadway in 1973, the same year The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie won the Oscar for best foreign-language film. The musical arrived at a moment when Sondheim, who had made his name with a series of highly plotted musicals that ran toward the comic and sentimental, was beginning to push the Broadway musical toward greater complexity — to, in some ways, share Buñuel’s aim “to change the world, to transform life itself.”

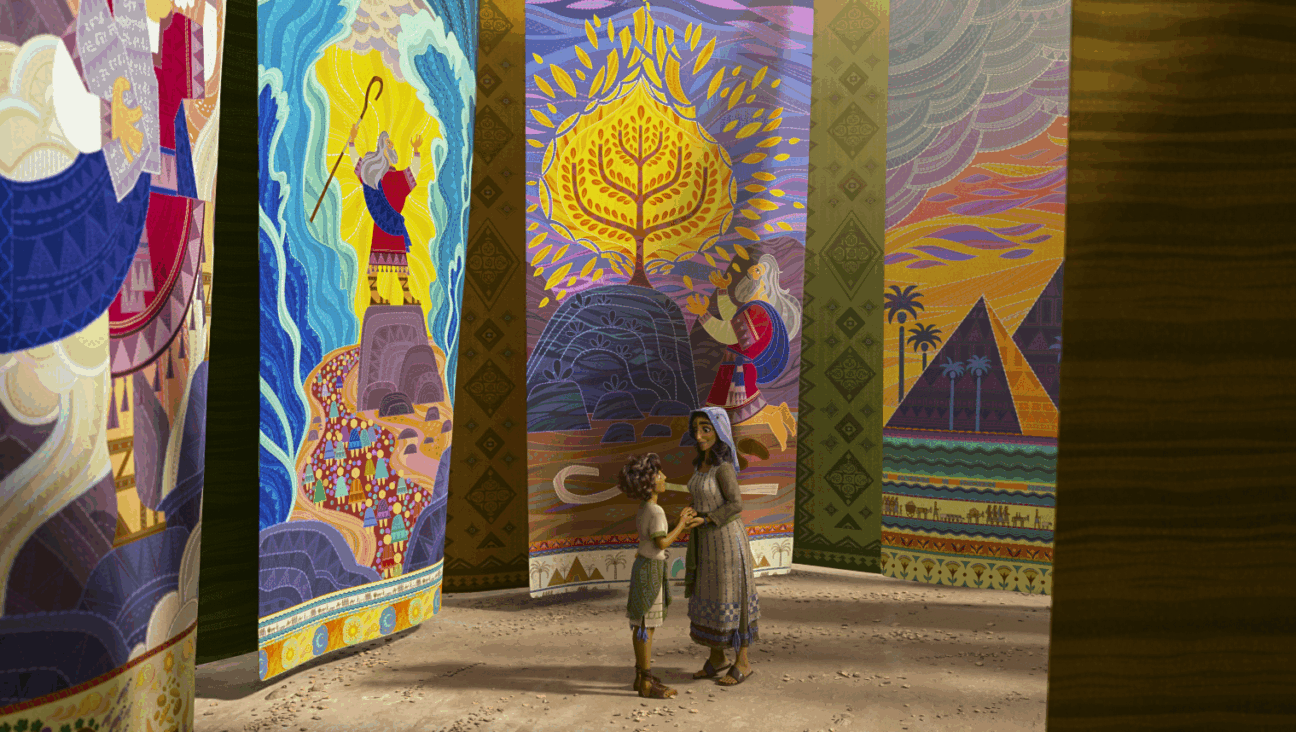

Fifty years later — with Sondheim having succeeded in remaking the musical in his image — his final show, Here We Are, inspired by The Exterminating Angel and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, will premiere off-Broadway in New York this fall.

American musical theater — or at least the stuff marketable enough to make it to the mainstream — tends to be plot-driven and morally unambiguous, two of the qualities that Buñuel was skeptical of in other artists. But Sondheim built his legacy on challenging the medium’s norms.

“Buñuel doesn’t have characters, and he doesn’t have plot, which is why we are having difficulty,” he told D.T. Max for The New Yorker in 2017. And it’s easy to see a confluence between the artistic preoccupations of Sondheim and Buñuel, despite the extraordinarily different circumstances in which they lived and worked. (Sondheim was a gay American Jew who made a home in New York City; Buñuel a Spanish rebel who grew up attending Jesuit schools.)

Both had a strong interest in classism, and the delusions of society’s elite. They imbued their work with severe skepticism about convention — artistic, social and otherwise — and were drawn to characters who harbored dark obsessions.

Above all, both focused in their later years — Buñuel died in 1983, Sondheim in 2021 — on the idea of the artifice inherent in theater, and the question of how it might be used to reflect complicated ideas about the role of performance in human relationships.

‘A great puzzle fan’

After writing a set of musicals that followed standard Broadway structures in the 1950s and ’60s — Gypsy, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Anyone Can Whistle — Sondheim began, in the ’70s, to focus on more nontraditional narratives and ethically confused characters.

Starting with Company, which premiered in 1970 — the first of five musicals Sondheim would premiere in six years, in a surge of creative invention unlike any other in his career — he began to push back, at least briefly, against the idea that theater should involve clearly drawn characters telling stories with a point.

In 1971, he described the art of writing lyrics as “an elegant form of puzzle,” and himself as “a great puzzle fan.” Nearly two decades into his career, it seemed, he was beginning to approach the bigger puzzle of narrative structure with fresh ingenuity. Company featured a non-linear narrative about a hero with no real personality: “Everyone else is a character,” Sondheim told The New Yorker in 2016, but the protagonist, Bobby, “is the vacuum in the middle.” Could audiences find a way to resonate with someone like that character, despite his fundamental ambiguity?

At the same time, Sondheim found that another great passion of his was losing its audience: the staging of elaborate, almost surreal game parties. In a 1993 New Yorker profile, Sondheim recalled a particularly good one: a 1968 scavenger hunt that led guests, in one step, to the “vestibule of a brownstone, where a small elderly woman (actually, the mother of Anthony Perkins, Sondheim’s fellow game designer) would beckon you upstairs for some coffee and a slice of cake.” (Tough luck: “Those who actually ate the cake stood no chance of winning: The clue was drawn in the icing.”)

That party was one of the last of its kind. “I don’t know — it just stopped,” Sondheim said. “Everybody outgrew them except me.”

It’s easy to see the set of emotionally charged sexual escapades that make up Follies and A Little Night Music — the musicals that Sondheim premiered after Company, in 1971 and ’73 — as an extension of his newly thwarted interest in involving his friends in intricately structured games. He and his collaborators on the latter show initially conceived of it as “a fantasy-ridden musical,” he said in an interview for Craig Zadan’s 1994 book Sondheim & Co. “It was to take place over a weekend during which, in almost game-like fashion, Desiree” — the middle-aged actress at the musical’s core — “would have been the prime mover and would work the characters into different situations.”

What might any of this have to do with Buñuel, and his comically brutal portraits of what happens when people find their efforts to socialize interrupted by the rampant chaos of the universe?

Sondheim was clearly thinking critically about the director by, at the latest, 1982, when he met James Lapine, the book writer with whom he developed Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods and Passion. During their first conversation, the pair discussed The Exterminating Angel and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Lapine recalled in his 2021 book Putting it Together. (Sondheim recommended the latter film, which Lapine had yet to see.)

It’s no surprise that Sondheim found Buñuel compelling. Even in adapting Bergman, whom Buñuel once criticized for “wasting himself on wholly uninteresting questions,” Sondheim had begun to consider themes that brought him close to the Spanish director: the savage comedy of social norms; the ways in which performance can create the false impression of an ordered universe; and the thrilling image of people, stuck with one another under contrived and bemusing circumstances, being treated as pieces in one grand, terrifying game.

‘An anarchist filmmaker-poet and moralist’

Both The Exterminating Angel and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie have deceptively simple premises. In the first, a group of guests at an extravagant dinner party find themselves trapped in a single room by a mysterious, imperceivable force. In the second, several upper-class friends meet repeatedly for a meal, but never manage to actually eat.

The films are known as much for their simultaneously urgent and veiled politics as they are for the entertaining inscrutability of their plots. (Buñuel famously never offered an explanation as to what the force keeping his partygoers hostage might actually be.) Born in Spain in 1900, Buñuel, after fighting with the Republicans against General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War, spent much of his career working in Mexico, as well as in France.

In their own strange, surreal way, his films worked to showcase the absurdity of power, and the link between that absurdity and violence. There’s a certain gamesmanship in the way he moves his characters about, a strange sort of predetermination to their existence that suggests some higher entity, somewhere, is pulling the strings.

That entity’s interference is alternately wished for and raged against. The guests in The Exterminating Angel invoke Masonic codes of conduct and enact a purported Kabbalistic ritual. They yearn for intervention, even when the only example of such intervention they can readily see — the inexplicable barrier keeping them in place — is ruining their lives.

What ultimately releases them — spoilers — is putting on a kind of play. Just as the tension between them threatens to turn murderous, one character realizes that everyone is occupying the same exact positions they were at the end of the party, just before they began to understand that they were trapped. They reenact their interactions from that first evening, and, miraculously, are suddenly able to leave.

What might that surprising mechanism of release suggest about the higher entity? Their escape calls to mind an exasperated director asking his cast to run a scene again, and please, get it right this time — as if he’s just been waiting for a run-through good enough to justify ending the rehearsal. There’s a horrible irony to the idea that, after spending weeks with their ability to perform social norms decaying, and something of the animal side of their nature emerging, all the guests had to do to ensure their escape was perform the same old routine of barbed graciousness one more time.

If the figure of the frustrated director is evoked by the end of The Exterminating Angel, he appears in the flesh in one of the more surreal scenes in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. The central sextet sits down to a meal, only to have a set of nearby curtains open to reveal a waiting audience: The diners are not at a restaurant, as they thought, but rather onstage. As they gawp at the audience, and the audience gawps back, a man pokes his head up impatiently from the orchestra pit, and begins feeding them lines. Some of the friends flee the stage immediately, but a few engage in a feeble attempt to follow his instructions.

The strange director’s frustration at their amateurishness is palpable. He embodies something of the message that Buñuel, in his many, profound anti-authoritarian urges, was perpetually trying to make: that the act of trying to seem powerful only makes the actor look foolish. That’s true for the poor pawns of The Exterminating Angel, too. It’s only when they accept that they have no control over their own fate that they are, briefly, pardoned from it.

‘Where are the clowns?’

In Sondheim’s late interviews, certain preoccupations stand out. He was troubled by how difficult the Buñuel adaptation was proving. He was thinking about death. Lifelong concerns he’d held about occupying a sort of spotlight were emerging: “I do not want to be looked at,” he said, once, frustrated by D.T. Max’s attempts to dig deeper into his artistic process. “End of it! I don’t want to be watched.”

And he was thinking about power — so much so that he and David Ives, he said, were basing characters in Here We Are on certain figures popping up in the news. (Which figures, exactly, he left unsaid, but Ives told Frank Rich of New York Magazine that the cast includes “a lively billionaire hedge-fund type,” “a charming Casanova who’s the ambassador of a tiny corrupt Mediterranean duchy” and “a hapless colonel from Homeland Security.”

“These are the American versions of the French bourgeoisie — you know, the movers, moneyed people, people in power,” Sondheim said. “Power is too big a word, but people who move society.”

Making theater or film, or any kind of art, is a way of playing God. Desiree acknowledges as much in the most famous song from A Little Night Music, “Send in the Clowns,” which begs for some unknown, unseen director to put an appropriate flourish on her heartbreak by sending in a cohort of clowns to complete it. Desiree is the show’s internal mastermind, but even she senses the presence of a greater, external intelligence setting the scene.

There’s an absurdity to the idea of an audience showing up to watch a group of people act out the same story, night after night, while those actors pretend — most of the time — that the audience isn’t there. What a kind of power it is, to believe you have created something worthy of such a strange, coded ritual.

And how strange that engaging in that ritual, rather than being seen as outlandish and bizarre, has become a totem for status.

Both Sondheim’s musicals and the kind of artistic, cerebral filmmaking for which Buñuel is known carry the aura, in popular culture, of being for a kind of elite. The Exterminating Angel opens with the dinner guests entering their hosts’ villa after an evening out at the opera; there’s an obvious self-satisfaction in their conversation about the work they’ve just seen. How civilized they are, in their lavish dress, with their lavish food, and their lavish opinions about what kinds of ideas are worthwhile.

Sondheim and Buñuel both understood that making art is, in its own way, an act of reaching for power. It is an attempt to define, for however long one has an audience’s attention, what is valuable for that audience to think about. Yes, part of the goal of art, for both, was to comment on power, and its innate preposterousness. But if art is also a tool for power, and an aspirational expression of it, what options for ethically free artmaking might that leave someone, like Sondheim, who would really prefer to avoid the whole circus — to not be watched?

Visiting Sondheim in his Connecticut home while he worked on Here We Are, Max noted a draft of some lyrics Sondheim was developing for the musical: “Life in this room, in this gor-geous God-damn room.” What is a theater, except a gorgeous goddamn room? And what are the audience and actors doing, living in that room together for a brief span, except attempting to separate themselves from the violence and ordinariness of life outside?

Here we are: the lucky few, within the room. And also unlucky, because the aims we might think we are pursuing — connecting to humanity on a higher level, coming to understand ourselves, refiguring our ideas about the world — are exactly what being in that room prohibits.

It is surprising to have the subject of a play turn out to be yourself — a point Buñuel made to hilarious effect in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. But it is also, in a way, inevitable. Sondheim had spoken, in 2017, of the trouble he was having with the vacant characters who populate Buñuel’s films. But that ambiguity also creates a brilliant opportunity. It pushes audiences to come up with their own understanding of the motives and emotions at play onstage. It forces them to fill in the blanks of the characters with what they know of themselves.

I wonder if the audience for Here We Are will like what they see. In one of the great, grim jokes of The Exterminating Angel, a crowd assembles outside the gates of the villa in which the guests are trapped to watch for signs of life. Really, they are watching nothing. It’s just a self-important house, full of self-important people, where something interesting might or might not be unfolding behind the scenes. “Where are the clowns?” Desiree asks, in A Little Night Music. “Don’t bother, they’re here.”

Performances of Here We Are begin Sept. 28 at The Shed.