How fast does TikTok send users down the antisemitic rabbit hole?

TikTok feeds its users videos with little input. What makes it feed them antisemitism?

Though innocuous on the surface, conspiracy theories abound down the TikTok rabbit hole. Graphic by Mira Fox

When I open TikTok, I mostly see cute videos of dogs, and inside jokes related to niche corners of my life — being a millennial living in Brooklyn with roommates, say, or working in journalism. There may be a few calming videos of cooking or crafts. The most problematic part of the app, for me, is its ability to hypnotize, making hours of my time vanish.

Yet according to an open letter Jewish creators on the platform released in November — which echoes what I’ve learned over several years of reporting —TikTok has an antisemitism problem, one critics say has reached new heights during the Israel-Hamas war. The CEO of the video app met with Jewish organizations and leaders in December to address concerns that it was driving and boosting antisemitism, and the issue has received extensive coverage.

So why, in my own use of the app, have I stumbled on antisemitism so infrequently — when I know for a fact it’s there?

The answer is, on its surface, simple: I’m not into conspiracy theories. The platform knows this, and after years of use — I signed up for my personal account in 2020 — its algorithm knows what I want (and don’t want) to see. The app steers me away from antisemitism so assuredly that it’s sometimes hard to find even when I’m actively looking for it in my role as a journalist, instead of absent-mindedly scrolling as an everyday dog-lover.

But I know other casual users do encounter incredibly hateful speech, twisted conspiracy theories and antisemitic harassment on the platform. So I wanted to see what TikTok might show an average, young new user — whether it would spiral into hate speech, and just how it would get me there.

To get any idea of what kind of videos TikTok might be serving up to its average user, I couldn’t be me: a 32-year-old Jewish woman living in Brooklyn who listens to folksy Jewish heartthrob Noah Kahan and, as my algorithm has recently realized, used to ride horses.

So I started fresh. And it turned out that my ticket down the rabbit hole was news — something many TikTok users rely on the platform for. When I looked for analysis and explanations of the Israel-Hamas war, I fell into a nest of conspiracies.

TikTok’s all-knowing algorithm

The reason my TikTok feed is so wholesome is because of the app’s algorithm, which is famously so adept at determining each individual’s niche interests that people have declared that the app knew that they were gay before they themselves did.

The algorithm’s complexity means that everyone’s TikTok feed is different. The video app works differently than other social media sites like Facebook, Instagram or X, formerly Twitter, where users largely see posts from people they follow, perhaps with some trending posts mixed in. Instead, on TikTok, users have little control over the videos they’re served. The main interface with the app is through the user’s homepage, called the For You Page — FYP for short — where they scroll through an infinite supply of videos served up by the app’s algorithm that play, one by one. A few might be from people they follow, but most won’t.

The FYP is populated by clips not-so-randomly chosen by an algorithm that watches users’ every move — noting not just what they like or comment on, but how long they linger on any given video, whether they play it through all the way, whether they click on a hashtag in its caption. Users are shown new videos based on inferences the algorithm has made about which posts are just similar enough to the ones they’ve already engaged with to stake a hold on their attention.

Even when users try to find new content through specific searches, they’re subject to the algorithm’s decisions of which videos to pull up. Posts don’t appear in chronological order, or even order of popularity. “Suggested searches” — clickable terms the algorithm thinks a user might be interested in based on what they’re looking at — pop up on videos they’re watching or as they scroll through search results, to direct continued browsing. The algorithm shapes every part of your experience in the app.

The insidious issue with this algorithmic approach comes when it exposes people to radical ideologies when they’re not actively looking for — an issue that has also arisen with suggested videos on YouTube. But at least on YouTube, viewers have to click on a suggested video to watch it; on TikTok, most of the time, the video just appears in front of them.

Video-based content is already difficult to effectively moderate, because problematic content might be showcased visually, without keywords an automated AI might be able to check. And TikTok users are known for inventing shorthand and coded language specifically to evade censorship. There’s corn — or even just a corn emoji — for discussing porn, or “seggs” for sex. In the world of antisemitism, “H!tl3r” or “that Austrian painter” helps users talk about Hitler without detection.

Combine the ease with which these videos escape moderation with the absolute power of the algorithm and it means that, at least theoretically, certain innocuous choices might be enough to prompt the app to suddenly begin to feed you hateful content — even if you weren’t looking for it.

The average TikTok simulacrum

To begin my experiment, I made a new profile, this one with a birthday in 2001 — the only information the app requests when you make a profile. Since concerns over TikTok users’ general youthfulness have been so prominent, I figured that I had better masquerade as Gen Z. I began to scroll, doing my best to move directly counter to my actual impulses to ensure I didn’t land, yet again, in DogTok. (TikTok niches often have nicknames like BookTok, which is about books, or FitTok, about fitness.)

The first video I saw was a clip of giant ships crashing through waves in a stormy North Sea. (For whatever reason, the dangerous waters of the North Sea are very viral right now on the app.) Then there was a makeup video, a few dances, some thirst traps. I was definitely seeing a part of TikTok that I don’t encounter on my regular account. But it was all innocuous and, if I’m being honest, boring. It was not immediately obvious how the app might choose to show me extremism of any kind.

Eventually, a clip appeared of a woman, her hand over her face, with text scrolling across the screen about God. The caption read: “If yu [sic] wanna be able to love you’re gonna have to desire a strong relationship with Jesus b/c HE IS love.” The short video had 1.8 million likes, and I let it play a few times as I explored the comments. These consisted mostly of: “amen” and “God is good!” But a few comments asked other users to pray their same-sex attraction away. This was the closest I’d seen to anything remotely hateful or discriminatory.

Lingering on that post — letting it play several times as I read the comments — immediately impacted my algorithm; my feed began to fill with Christian preaching videos. But after several hours of concerted scrolling, wondering if being on Christian TikTok would ever bring me to, say, videos of Christians accusing Jews of killing Jesus, I realized I was getting nowhere interesting.

All the videos were inspirational, about how this video was meant to find you — yes, you! — because God loves you no matter what mistakes you may have made. That’s sweet, if not very compelling when you get 10 in a row. But mostly, it’s cheerfully bland. Mainstream Christian content, it seemed, was not going to lead me to extremism.

But once you begin viewing content about Judaism, and especially about Israel, that changes.

Searching sideways

While going fishing for antisemitism seemed like it would violate the terms of my experiment, I had to do something to expand my FYP past lip gloss and sermons. So I searched for videos about “Israel vs Palestine” — a suggested search that appeared as soon as I typed the first few letters of “Israel,” indicating its popularity on the app. (Actually, it suggested I spell it “Palatine,” which is either strategic censorship evasion or just a really common typo.)

The initial search produced largely normal videos — people arguing about the politics, sure, but a well-balanced split of opinions. But nestled in my results about the war, TikTok offered me a box of related search terms, including: “Judaism religion debunked.” Curious, I clicked.

This, it turns out, is one way to stumble down the rabbit hole. Choosing one slightly odd search suggestion was enough to lead me to more suggested searches offering increasingly out-there search terms. It didn’t take long to land in a nest of extremism.

The first video I was shown about “Judaism religion debunked” was a Christian explanation of why Jewish law is unnecessary given the existence of Jesus; basic Christian theology, really. But the second video was about the antisemitic Khazar conspiracy, a false belief that today’s Jews are “not real Jews” and are, instead, descended from a tribe in the Caucasus and now attempting to take over the world.

The video was actually debunking the conspiracy, although apparently unsuccessfully. In the comment section, nearly every user was arguing that the Khazar conspiracy is true.

From here, I followed a path I imagined any curious user might; I searched for “Khazar.” After all, no matter how well-intentioned, efforts to debunk conspiracies can often instead serve to introduce them to new audiences and help them spread.

That search landed me in an endless feed of videos promoting the antisemitic conspiracy — preachers saying the Khazars are secret devil-worshippers; Hebrew Israelites accusing Jews of usurping their identity; fake historians pointing at maps explaining the origin of the Khazars.

From there, I clicked on a hyperlinked suggested search term on the first video, which said “Benjamin Freedman knew this first.” This brought me to a series of videos reposting a 1961 speech by Freedman, a noted Holocaust denier, in which he alleges a “Zionist scheme” to start wars in an attempt to amass power.

Down the rabbit hole

From my first innocuous search about the war, it only took a few clicks to enter the world of antisemitic conspiracists. Doing so changed my entire feed.

When I returned to my FYP, the posts had become increasingly conspiratorial; the inspirational sermons were gone. The videos I was receiving weren’t necessarily antisemitic, but they involved a lot of magical thinking and anti-government suspicion. There were posts alleging that the Mandela Effect is proof of a government psyop, and a series of videos claiming that police had covered up the appearance of giants walking the streets in Miami, which some users said were “nephilim” — biblical creatures that signify the impending apocalypse.

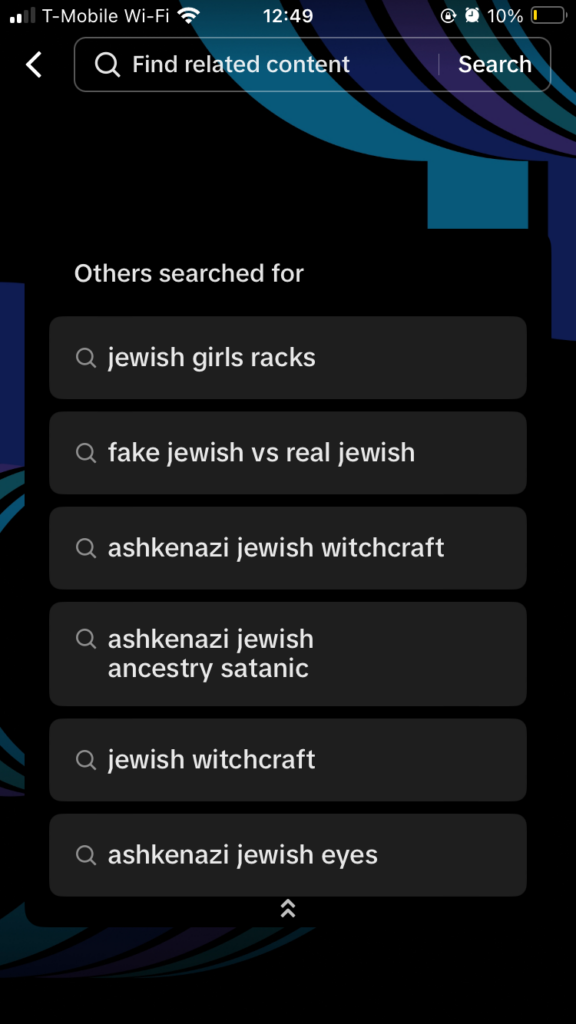

And, as I continued to scroll, things got more Jewish. My FYP showed me a video of a rabbi discussing the concept of Jewish chosenness in a neutral way — it seemed mostly normal. But then I clicked the suggested search at the top of the comments, which was, oddly, “Jewish wrist,” which led me to videos about people tattooing numbers on their forearms. The suggested searches attached to those videos included options such as “fake Jews vs. real Jews” and “Ashkenazi Jewish witchcraft Satanism.”

I’d come across a wealth of false antisemitic conspiracies. All the classics, really: blood libel, demon-worship, world-governing cabals.

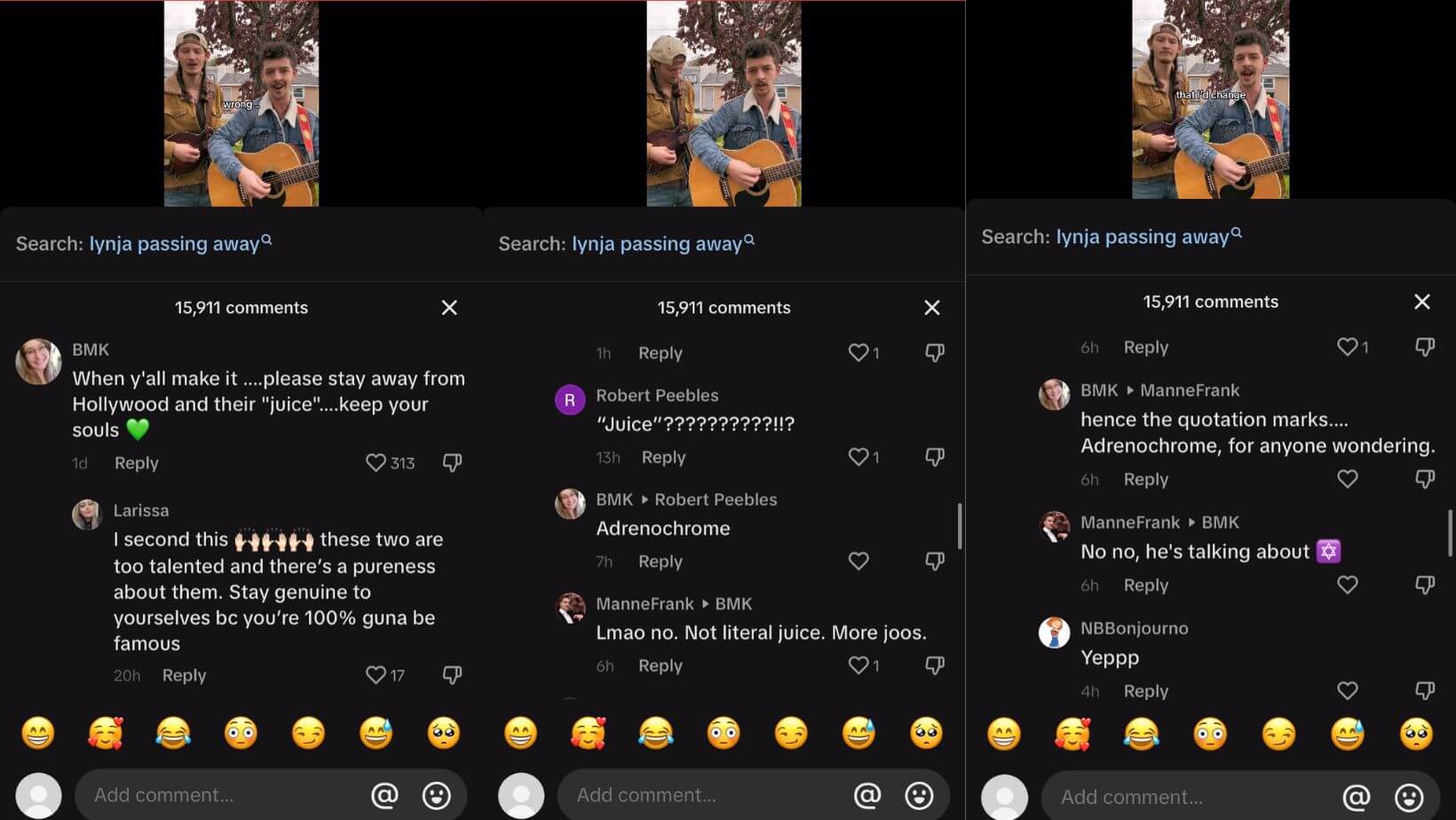

Even the comment sections on seemingly-innocuous videos that popped up on my FYP became increasingly full of antisemitism. On a video of a music duo singing a country song, users congratulated the singers for going viral and getting popular. But commenters also warned the folk musicians to avoid the “juice” once they got to Hollywood — clarifying in subsequent comments that “juice” meant “the joos,” or, yes, the Jews.

Eventually, I began to see antisemitism appearing natively on my FYP. It wasn’t constant — there were still videos about the snow storms sweeping across the U.S. in January, girls complaining about bad breakups and videos about how oil pulling can whiten your teeth. But every few videos, I’d get someone talking about the secret powers controlling the government, or the mysterious, demonic families controlling the banks. Videos were peppered with references to a mysterious, all-powerful “they.”

Even if the Jews weren’t named, it’s clear who they meant.

So is TikTok antisemitic or not?

As I found my way into the world of TikTok antisemitism, I did my best to behave as I thought an average person might — someone who isn’t predisposed toward conspiracy theories or antisemitism, but who doesn’t know much about how to avoid them, either.

It’s certainly possible to never end up in an extreme corner of TikTok; my FYP could have easily remained a bland, infinite stream of dances and make-up tutorials and sermons. Still, it’s just as easy to land in a nest of conspiracy theories simply by looking for videos about the news.

I never searched directly for antisemitism, conspiracies or hate speech. But if the app suggested the idea to me initially, then I went along with it.

Sure, the first video on the Khazar conspiracy I got wasn’t endorsing it, but if I were someone who had never heard of Khazars before, I might want to learn more by searching for the term — at which point I’d see hundreds of videos arguing for the conspiracy’s truth. And so on.

I asked Imran Ahmed, CEO of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, why social media platforms continue, after years of criticism, to enable conspiratorial spirals like this.

“Their business is keeping you on the platform, so they prioritize things that capture your attention,” he said. “A conspiratorial mind is fertile ground for algorithmic cross-fertilization, deepening and broadening.” The more time a user spends engaged, the more revenue the platform makes. So once the algorithm has figured out that one conspiracy theory holds your attention, it tries to show you more — maybe you’ll enjoy a new conspiracy you’ve never heard of.

This means that even simple curiosity about a conspiracy theory can immediately embed a user in a world in which every video is arguing that there are secrets in the world. It trains users in the kind of rampant suspicion and conspiratorial thinking that can guide them farther down the rabbit hole.

Sure, other social media platforms can suggest these ideas too — X offers a list of trending terms, and if the Talmud is trending because people are posting about how it’s full of evil secrets, users will get introduced to that idea.

But at least on X, those conspiracies have to be fairly mainstream to make much of an impact. On TikTok, if you demonstrate even the slightest interest, the app is happy to guide you further into the world of conspiracies. You can suddenly land on a nest of videos with just a few hundred likes — barely anything in the world of TikTok — but the algorithm will still bring you there if you follow its suggestions.

And once you do, they’ll become inescapable; videos about Jewish devil-worship will pop up between videos about the perfect scrambled egg as though they’re just as plebeian, teaching you conspiratorial thinking alongside cooking techniques.

“We call that rabbit-holing,” Ahmed said. “But the platforms just call it, basically, a captive audience.”