A mural of the Simpsons as Holocaust victims should be offensive. It’s actually a stroke of genius

Muralist aleXsandro Palombo’s use of ubiquitous cartoon characters startles viewers out of preconceived notions about the Holocaust

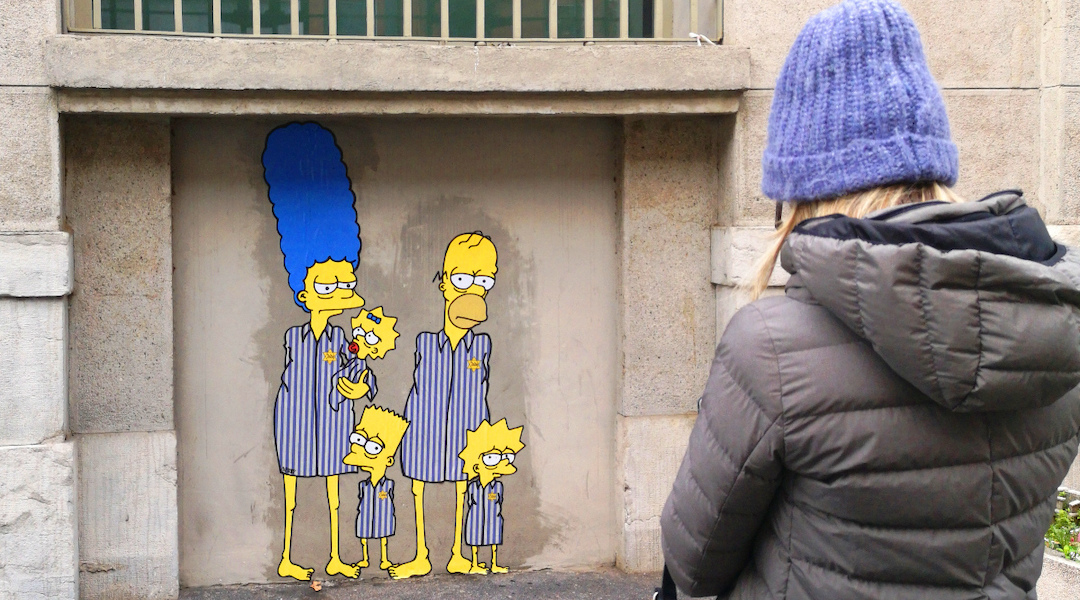

Artist aleXsandro Palombo painted several images of characters from The Simpsons on the outside of Milan’s Holocaust memorial. Courtesy of aleXsandro Palombo

The Shoah Memorial in Milan saw four unusual visitors arrive last year on Holocaust Remembrance day. The Fox TV animated characters Homer Simpson and his wife Marge, along with their three children, Bart, Lisa and Maggie, appeared in mural form on the exterior wall of the city’s central train station, which since 2013 has housed a memorial to the city’s murdered Jews, who along with political prisoners and others were deported to Auschwitz and other German camps during World War II. The first of two panels depicts the Simpsons as Jews dressed in overcoats marked with yellow stars. Their faces illustrate a resignation to the fate of many Milanese Jews who were packed into box cars at that train station and deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz. The second panel presents the family at Auschwitz, emaciated, and wearing the infamous pajama-like uniform.

The mural is shocking for being both brightly colored and a cartoon. But the artist behind it, the well-known Milanese fashion designer and street artist aleXsandro Palombo, did not intend the work as a joke or an insult. Like much of his street art, the mural simply appeared one morning without warning or consultation with officials at the Shoah Memorial. Shortly after debuting the piece, the artist issued a statement deploring the horrors of the Shoah and explaining his work as “a visual stumble that allows us to see what we no longer see.” Palombo believed he was transmitting a vision of the Holocaust to a “new generation.”

By “visual stumble” Palombo was probably referring to the street art called stolpersteine (“stumbling stones”), a concept created in 1992 by the German artist Gunter Demnig. Embedded in sidewalks across Europe, Stolpersteine are brass plaques marking the locations where Jews and other Holocaust victims lived immediately before they were captured and deported to their deaths. Demnig credited the idea to an idiom popular during his youth in the postwar era, when Germans who tripped on the street for no apparent reason laughingly said they must have “tripped over the grave of a dead Jew.” He hoped that people would not just walk past his stolpersteine, but stop and remember the victims of the Holocaust as human beings. Stolpersteine arrived in Milan in January 2017, and today 171 markers commemorate a small fraction of the city’s deported Jews. In explaining the motivation behind the Simpsons mural, Palombo may have been referencing Demnig’s stolpersteine, which likewise attempt to stop people in their tracks and force them to think about the Shoah.

One group that was certainly caught unawares by Palombo’s mural was the Milan Shoah Memorial Foundation. The organization’s leaders said they were not “involved in the decision process,” but that they appreciated the piece and didn’t “find it particularly harmful.”

That lack of criticism may reflect the fact that Palombo is not new to Simpsons-related Holocaust art. In 2015, for the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, Palombo released a series of illustrations, titled Never Again, which portrayed the Simpsons in front of the camp’s gateway sign bearing the slogan “Arbeit Macht Frei”; beside the crematoria; and on the train tracks leading to the gas chambers. One work depicts Bart Simpson with his arms raised in a pose reminiscent of the photograph of the Warsaw Ghetto boy surrounded by armed Nazis. Palombo described the series as “an invitation to reflection, an artwork to raise awareness, an indictment against intolerance, a punch to inhumanity.”

Antisemites took the Simpsons mural as a provocation. Just a few months after it was revealed, a vandal blacked out the characters’ yellow stars and left scratches across the mural’s surface. In January, someone scrawled the words “Fuck Israel” and “Viva Hitler” above Homer’s head. But that was not the first time it was vandalized. The work was defaced again on June 5, 2023.

Palombo’s art has also faced more thoughtful criticism. In a 2015 essay for the Forward, critic Anna Goldenberg voiced her fears about Palombo’s mixture of pop culture and the Holocaust. She was concerned about the impact of the images on a generation that is ignorant of the Holocaust and who might not understand the gravity of what is being depicted.

James Young addresses similarly provocative art in his book The Stages of Memory, which comments on a notorious 2002 exhibit at New York’s Jewish Museum titled Mirroring Evil: Nazi Imagery/Recent Art. The exhibit included a work called Prada Deathcamp, a photoshopped image of concentration camp victims drinking Diet Coke and even a Lego model of the crematoria. Those works certainly had detractors, but Young concluded that three generations after the Holocaust, there exists something he calls the “afterlife of memory,” that is, the experiences of survivors’ grandchildren, which are necessarily mediated through television, movies, novels and plays. Many people born in the generations since the Holocaust only know of the destruction of European Jewry through pop culture. Their art, like Palombo’s art, expresses that distance.

But the popularity and familiarity of the Simpsons is not ultimately what makes them interesting as Holocaust victims. What is conceptually interesting about animated characters in general, the Simpsons included, is that they never age, never suffer and never die. Cartoon violence allows characters like Wile E. Coyote, Donald Duck and even Itchy and Scratchy (the protagonists of a fictional cartoon series depicted in The Simpsons) to be sliced, diced, dropped from cliffs, hammered with boulders, and targeted by a variety of missiles without ever suffering. They are immune from trauma because they are only cartoon characters. Recontextualizing the Simpson family at Auschwitz in a landscape of suffering imbues the characters with vulnerability shocking to viewers who know them as ageless beings impervious to harms. Consequently, Palombo’s art does not make Holocaust victims cartoons. It makes the cartoon characters human, and it humanizes them as Jews. Palombo transforms the Simpsons into human beings, and more than that, Jewish human beings. This is not a mere trick. It is a profound artistic choice.

In this sense, Palombo’s closest analog may be the graphic artist Art Spiegelman, who depicted the Jewish subjects of Maus as cartoon mice in order to highlight their vulnerability. Palombo took his cartoon subjects and made us see them as Jews in order to portray their vulnerability and their humanity. Surely, there are myriad ways to use art thoughtfully in the service of Holocaust understanding.