‘What’s Kosher?’ An Indian-Jewish poet’s take on memory, belonging, and her people’s delicious history.

Zilka Joseph’s new of book of poetry, ‘Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman,’ dips into the culture and mythology around the subcontinent’s largest Jewish community

Zilka Joseph said she wrote this collection of poetry to bring to life bygone memories of late family members and the home she grew up in in Mumbai and Calcutta. Courtesy of Zilka Joseph

In the poem “Not One Fish,” Indian Jewish author Zilka Joseph shares the story of how her community, the Bene Israel, connected with the wider Jewish world. Legend has it that in the second millennium C.E., David Rahabi, a Jewish visitor to the Konkan coast of Western India, encountered people who recited the Shema, circumcised their children, and observed the Sabbath. The women of the village prepared a feast for their guest.

“Would they pick crab and shrimp?/ Mussel, clam, or bottom feeders?/ No./ Not/ one/ fish./ Not one/ fish/ without/ fins and scales/ had they chosen.”

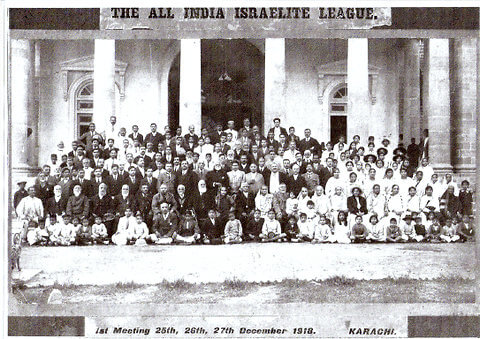

Rahabi determined that his hosts were fellow Jews who had lost touch with some of Judaism’s strictures. He helped revive formal Judaism among a population that would, by the 1940s, number some 25,000 Jews.

No one knows for sure how India’s largest Jewish community ended up on India’s Western coast. They could be the descendants of a shipwreck of Jews fleeing Antiochus’ reign in Judea in the second century B.C.E.; immigrants from Persia or Yemen in the fifth or sixth century C.E.; or members of one of the ten Lost Tribes of the Kingdom of Israel.

In Joseph’s new book of poetry, Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman, she plucks vivid moments out of her people’s mysterious history, as well as her own experiences in a community that has shrunk to just 5,000 in India today (most have emigrated, with the vast majority — around 80,000 — living in Israel).

The book’s title refers to the “Malida,” an offering of rice flakes, nuts, coconut, fruits, and flowers to the prophet Elijah, a central figure in Bene Israel tradition. As Joseph celebrates — and interrogates — her community’s memories, food is central, a medium for welcoming newcomers, remembering her family’s matriarchs, and launching questions into historical gaps.

In “Pantoum for Chik-cha Halwa,” a coconut-and-wheat-based dessert helps her plumb historical gaps as she writes, “so very different from sweets of home/ sugar coconut milk colored pink thickening/ those lost in the deluge shipwrecked/ would their spirits whisper old recipes?”

And in “The Angels of Konkan,” she expresses gratitude for those who fed her shipwrecked ancestors: “As Elijah ate of bread and flesh/ the ravens gave him so also we ate/ and drank of the cool water brought/ from brooks.”

Joseph was born in Mumbai, grew up in Calcutta and has now spent years as a writer, teacher, and editor in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She’s been a food obsessive since childhood. This book was born as she tried to recreate memories of a home, and family members, that were no longer with her.

I spoke with Joseph over video chat about the role of questions in her writing, the diversity of the India of her youth, and the importance of ravens and crows. Scroll down for an excerpt of the collection’s namesake poem, “Sweet Malida.”

You incorporate a lot of questions into your poetry. What role did questions play in your writing process?

I’m almost asking my ancestors questions when I write. I’m asking, “How did it feel to be shipwrecked on the sands?” “What does it feel like to be rescued?” “What does it feel like to be clothed and fed by these strangers?” And then, “How did it feel to cook certain things?” “How did this community grow as they lived in these villages in the Konkan?”

In several of your poems, you mention growing up around people of different religions. Why was it important for you to write about that?

I am celebrating the fact that diversity was so intrinsic to our lives that we never thought about it. We would hear prayer bells, and then somebody was lighting incense in a nearby building, and a smell would come by, and somebody was cooking kabobs on the street, and another smell would come up from the little Muslim shop downstairs. If your neighbor came over for a cup of tea, and she cooked something that day, she might bring you a little bowl.

In parts of India, Muslims and Jews lived together in the same neighborhood, because their cultures were so similar. It’s not till later on when some of the conflicts arose in the Middle East that there were some tensions. In many of the synagogues, the caretakers are Muslims, and have been for generations.

I just feel blessed. I think it’s wonderful to have this richness, you know? Of culture, and life, and food. It made me who I am.

What was your relationship like with other Jews when you were growing up in Calcutta, the center of Baghdadi Jewry in India?

I knew a few of the Baghdadi Jewish families. We knew a Baghdadi Jewish family called the Zacharias, and they were great friends. They would have wonderful feasts that we would attend, with aloo makala (a Baghdadi Jewish fried potato dish), and chicken roast and all of that.

How did it compare to the food that you would eat in your Bene Israel home?

Their food is Middle Eastern cuisine. Ours was more akin to Maharashtran cooking from the state of Maharashtra, where Bombay is situated. The West coast of India has a lot of similar foods. There’ll be rice, they’ll be coconut, and there’ll be fish.

In some of your poems, you write that people might have labeled you “impure.” Who is it that called you impure, and why?

When I say these words like “impure,” I’m bringing into play how a lot of communities that are not mainstream are often looked at. .

There is this question of whether you are a “true Jew,” or “half-blooded.” In the history of the Bene Israel, and other immigrants, in Israel, they faced a great deal of discrimination. For a long time the rabbis did not accept Bene Israel Jews. Same thing with Ethiopian Jews.

Even within the Indian Jewish community, we talk about the “Black Jews,” and the “White Jews,” and the ones who have intermarried. I’m not blaming anybody. It’s how these structures form and how, within history, these hierarchies exist.

At the same time, in some poems you express gratitude for the villagers who welcomed your ancestors.

You’re absolutely right, because in ancient India, there was little religious persecution. So even though these strangers were shipwrecked on the shore, they were allowed to live among the villagers and follow their beliefs. They took on all these various occupations: oil pressing, farming. There were no questions asked: “You live here now, you can live in our villages, work among us.”

If one of them had been hostile, they could have just killed that whole community. But instead, they were just good human beings that saw these people half-drowned on the shore — as I imagined them to be — in a shipwreck after a storm. And they embraced them.

What mark do you want this book to leave on the readers?

We need to learn about and embrace all Jewish cultures— not just [know] that these cultures exist. Who are these people? What did they do? What were they like? Where did they live? Where are they now?

In America, one of the things that startled me in the beginning is how little people knew about non-Ashkenazi Jewish cultures, such as Sephardic, Mizrahi or Chinese Jews. So I hope readers will truly be curious and enjoy these different cultures.

Many of the poems in the collection focus on crows and ravens. What’s their significance to you?

If you grew up in India, crows and sparrows are in your face all the time. If I was recording this conversation there, there would be a chorus of bird calls. They’re nesting in your houses and on the parapet.

In the story of Elijah in the desert, God told the ravens to feed and tend him morning and night. If you see pictures of Elijah, he’s in the desert with his wild hair, and the ravens circling above him. I connected that with Noah’s raven.

Crows and ravens get a bad rap. So I think, “Well, God created the raven, too.” How do we reconcile these ideas?

It’s the other place in the book where you use the word “impure.”

Yeah, because in many cultures, there are certain animals that are considered unclean or taboo.

Even Jews do that.

Exactly. Very often, something is villainized, and that makes it an outcast. It’s always suspect. On the one hand, ravens are messengers of God feeding Elijah in the desert. On the other hand, you have this image of the raven as an evil figure — an angry figure that’s not trustworthy. But if the Raven had not gone out and stayed away, then Noah would not have known that the land was dry. So there’s a purpose to its existence.

So what do we look at as bad or good? Or evil or clean? And unclean? What’s kosher? [Laughs]

Are you half a Jew? Are you a half-breed? Who’s a Jew?

“Sweet Malida” by Zilka Joseph

(excerpted with permission from Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman, Mayapple Press 2024)

Sweet malida,

a mix of water-softened

flattened rice, sugar,

dried fruits and nuts,

was a dish made

for Shabbath, or for breaking

our fasts. Cooling, light

on the palate, and

to the body and the spirit,

it was welcome in the heat

of day or night. We had many foods

in common with our Muslim,

Christian and Hindu neighbors,

and we often celebrated together

their festivals or ours. I relished

particularly fresh coconut,

the regional staple, its milk

or its flesh added to almost

every dish. But this was to me

the best way to eat it;

finely grated

by my mother’s hands,

left unsweetened

and sprinkled haphazardly

on the malida, juicy threads

with a fleck of stubborn

brown kernel here and there

that sometimes crunched

in your teeth like sand,

and you winced and swallowed it,

knowing that there was no

simpler or purer

or truer form than that.