Why a museum on prewar Jewish life in Europe was envisioned for New York, but never built

YIVO’s Museum of the Homes of the Past was both too early — and too late

Shaye Leyzer Ain stands at the tombstone of his mother, Sore Khane, in Swisłocz, Poland, 1920s. The photo is one of hundreds of photographs donated to YIVO for the Museum of the Homes of the Past. Courtesy of YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

World War II was still being fought when a new institution was envisioned in New York called the Museum of the Homes of the Past. It would depict ordinary life before the war in Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe and offer a way for American Jews to connect with their heritage.

The project was developed by YIVO, the Yiddish Scientific Institute, which moved its central headquarters to New York from Vilna, Lithuania, shortly after the war broke out in 1939. The museum project was announced in 1944; by then, it was clear that the communities to be showcased by the museum were being annihilated. The museum would be a memory palace for that vanished world.

But the museum was never created. In a new book, Homes of the Past: A Lost Jewish Museum, scholar Jeffrey Shandler shows how this abandoned project reflected the grief, dislocation and changing priorities of the American Jewish community during the war and postwar years.

Shandler, a professor of Jewish studies at Rutgers University, will give a talk about Homes of the Past for YIVO via Zoom on June 24. I recently spoke with him about how he came to write the book, and what this lost museum represented in the 1940s — and now. Our Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Since the museum was never built, how did you know about it?

I was planning a sabbatical for fall 2020 to work on a project about contemporary Jewish museum practices around the world. Then the pandemic hit. I started to think about what I could pursue while stuck at home. I was looking at online materials at the Center for Jewish History (which YIVO is part of) and the subject of “lost museums” emerged — that is, museums in Europe that were destroyed during the war, as well as museums that were planned but never created, such as this one.

Early in the pandemic, you couldn’t go to museums; they were closed. And there was a concern that if this went on long enough, some museums wouldn’t reopen. So what does it mean when you lose a museum — even a museum you never visited? That’s what I homed in on. The story of this museum particularly intrigued me, because I had worked at YIVO in the 1980s and had been a student there, but this “lost museum” was something I didn’t know about.

What were you able to find out about the project?

What YIVO’s archive has are the documents of the planning process, including carbon copies of letters that were sent to everyone who donated something for the museum. These letters also asked the donors follow-up questions, such as, “Tell me as much as you can about your family and your hometown.”

What did YIVO collect for the museum?

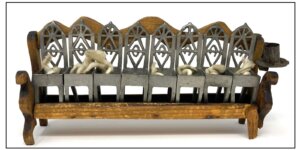

YIVO collected hundreds of photographs and documents for the museum, but very few objects.

One of the things I found striking was that people would be willing to give YIVO anything at this time. I mean, the war is on; you don’t know if your family is still alive, and all you have are these photos. The willingness to give them to YIVO was very impressive. The idea that you were contributing to what YIVO characterized as a national project spoke to people.

They’d also issued an earlier public appeal, before the museum was launched, for people to donate any letters they had from family back in Europe. They’d say, “Those letters, you’re going to throw them out. For us, they’re really valuable resources.”

You write that YIVO planned to organize this project geographically, with individual exhibits about all the places where Jews lived in Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europe. Sounds like a great website, but how would it work as a museum?

The museum they had in mind wasn’t like the Jewish museums that existed previously, which displayed ceremonial objects or works of fine art. For them, geography was very important. The Galician Jews are different from the Vilna Jews, and so on, and YIVO wanted to show the extent and variety of Jewish life in this large swath of Eastern Europe where Yiddish-speaking Jews lived. They would have organized the museum by region, and within regions, by town.

There are websites like that today, like the Virtual Shtetl on the website for Warsaw’s POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. In a way, YIVO was anticipating people saying, “I want to learn about that town.”

You say in the book that the museum proposal was both too early and too late. What does that mean?

It was too late because the idea of a museum celebrating Yiddish-speaking Jews as a distinct nationality was rooted in the sensibility of Eastern Europe before World War II. This idea did not speak to American Jews in the 1940s and ’50s.

As to why it’s too early, it took about a generation for American Jews born after the war to get interested in this past as a resource. They were not driven by a sense of personal loss but by a sense of discovery. It’s like, “Who knew this stuff? This is remarkable!” So a lot of this gets realized by a different generation starting in the 1970s.

So in this way, YIVO was ahead of the curve. It anticipated projects that YIVO and others produced during the postwar decades, including YIVO’s Image Before My Eyes (a 1976 photo exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York about prewar Jewish life in Poland).

Why did YIVO abandon the museum?

I don’t really know. It might have been financing. Putting up a museum is not inexpensive, and YIVO was struggling to find money for publications and research projects. And they had other priorities, especially getting back material that Germany had looted from YIVO in Vilna during the war. Max Weinreich (YIVO’s director of research) started working on that before the war ended, making the case that the material should come to New York. He feared that, if the material were repatriated to the countries where the institute had been before the war, YIVO might never see it again.

At the same time, YIVO started collecting and documenting and researching what we now call the Holocaust. They were at the forefront of Holocaust studies, and that was a different mission from the Museum of the Homes of the Past. And it had a certain urgency, before things disappeared, to gather material and start the effort of writing this history.

Talk about the moment that the raison d’etre for YIVO changed.

It’s a remarkable moment. I found it so moving. The people at YIVO were recent immigrants or refugees who were so invested in Jewish life in Eastern Europe. Their mission had been to help build a better future for Jews there. But then there was this terrible realization — that there would be no future there. And so the question was, what do you do now?

At one point, a member of YIVO’s board went on WEVD (the Forward’s Yiddish-language radio station) to talk about the museum project, saying, “You know, people are being killed and there’s not going to be anything left.” One can imagine an emotional delivery of that statement from reading the transcript of his remarks. But for the most part YIVO was focused not on the destruction, but on what they needed to do to move forward. And maybe making plans for the museum was one way to keep themselves from sinking into despair.

I think for YIVO’s scholars in New York, there was, in addition to their personal grief, an institutional crisis: “What can we do as an institute to memorialize this world that is lost, and what can we do to continue to share what it has to offer to the future?” That’s the attraction of the museum. YIVO started to think about what American Jews, especially the children and grandchildren of immigrants, need to know about this past and how to present it to them.