July 4th hot dog debate: Nathan’s kosher-style vs. Joey Chestnut’s Impossible choice

Eating hot dogs is a July 4th tradition, even without Joey Chestnut at Nathan’s Famous contest

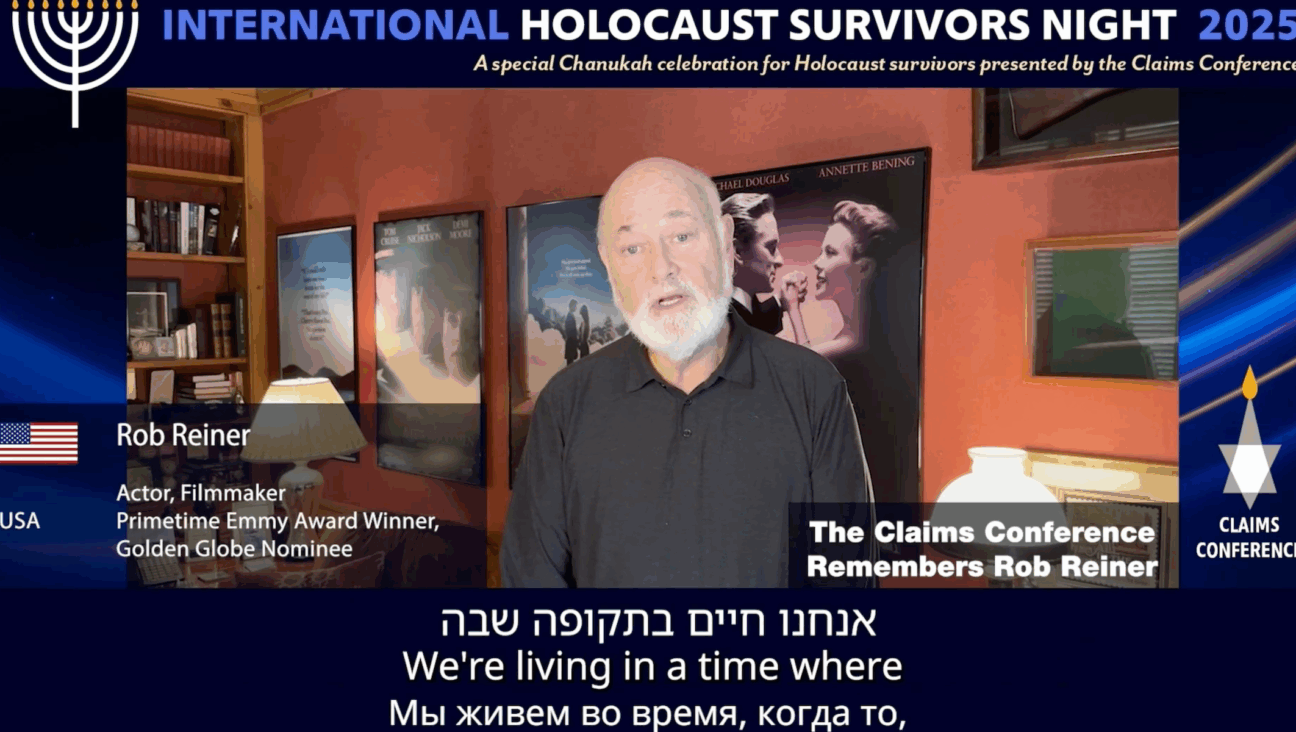

Joey Chestnut, left, and Miki Sudo hold 63 and 40 hot dogs respectively after winning the Nathan’s Famous 4th of July 2022 hot dog eating contest on Coney Island. Photo by Yuki Iwamura/AFP via Getty Images

When it comes to hot dogs, there’s always a nagging question in the back of my mind (and possibly yours): What are they made of, exactly?

That’s why, even though I don’t keep kosher, on the rare occasion that I do eat a hot dog, I prefer a kosher brand. But now, thanks to Joey Chestnut’s endorsement of Impossible Foods’ vegan hot dog, I’m wondering if I should forsake my usual go-to, Hebrew National, for meatless.

Chestnut is the longtime champion of Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest, held each July 4th at Nathan’s flagship restaurant on Coney Island. That’s where the Nathan’s brand — which last year sold 700 million hot dogs around the world — began more than a century ago.

The contest will go on as usual in Brooklyn this week, but Chestnut won’t be there. According to various reports, he first demanded a bigger appearance fee from the event organizers, which they agreed to, but then sought the OK for his Impossible endorsement and his participation in another hot dog competition, which apparently were deal-breakers. “It would be like back in the day Michael Jordan coming to Nike, who made his Air Jordans, and saying, ‘I am just going to rep Adidas too,’” contest promoter George Shea told The New York Times. “It just can’t happen.”

All this talk of hot dogs made me hungry, not just for something in a bun, but for more information. My requests for comment from Chestnut, Hebrew National, Impossible and Nathan’s all went unanswered, but I Googled around so you don’t have to. Here’s everything you need to know about hot dogs, kosher and otherwise.

Is Joey Chestnut vegan now? Is he Jewish?

Chestnut apparently remains a meat-eater despite his deal with Impossible. He is taking part in a non-vegan hot dog-eating contest on July 4th in Texas and another one on Labor Day.

Chestnut’s middle name is Christian, so I presume he is not Jewish.

What’s happening with the Nathan’s contest? And are Nathan’s hot dogs kosher?

There are separate 10-minute competitions for men and women, and the winner of each gets $10,000 (and likely a stomachache). Last year, Chestnut won the competition for the 16th time, downing 62 dogs in 10 minutes.

The contest has been held nearly every year since 1972 at Nathan’s Famous original restaurant, located at the corner of Surf and Stillwell avenues in Coney Island. That’s where Nathan Handwerker, a Jewish Polish immigrant, and his wife, Ida, set up a stand in 1916 selling dogs from a family recipe for a nickel apiece.

Nathan’s dogs do not have the rabbinic stamp of approval needed for certified kosher food, but because they’re all beef, Handwerker called them “kosher-style.” (Not only do they exclude pork, but apparently back in the day, it was a selling point for him to say, “No horsemeat!”)

Thousands of people typically turn out to see the competition live, just steps from Coney Island’s beach and amusement parks. Another couple of million watch it on ESPN, beginning at 10:45 a.m. EST.

Are hot dogs actually gross?

Honestly I wish I hadn’t researched this one. I knew that hot dogs are typically loaded with sodium nitrate, salt and fat — which is why, even though I love them, they are, for me, a special treat reserved for a trip to a ballpark or a once-a-summer barbecue. And I already had some vague notion that they may also include ingredients I’d rather not think about. But reading the details about what is permitted under government regulations in hot dogs (organ meats, anyone?) is enough to make me want my own deal with Impossible Foods.

Are Hebrew National hot dogs better? Do they really answer to a higher authority?

I’m old enough to remember that legendary Hebrew National commercial from 1975, where Uncle Sam holds a hot dog while a deep God-like voice (if God had a voice) says: “The government says we can use artificial coloring. We don’t. They say we can add meat byproducts. We don’t. They say we can add non-meat fillers. We can’t. We’re kosher. We have to answer to an even higher authority.”

It made an impression on me then as a kid, and it still impacts my choices as a consumer decades later. I typically spend time in Maine each summer, where “red hot dogs” — apparently called that because they are dyed bright crimson — are a local favorite, with a festival to prove it. But if I’m grocery-shopping for a barbecue while I’m there, I still hold out for the Hebrew National — and I can usually find them, even in supermarkets in rural parts of the state. There aren’t a lot of Jews in Maine, so the fact that you can get Hebrew National hot dogs in Skowhegan, population 8,000, tells me that I’m not the only one looking for them there.

I’m also oddly comforted, though I’m not sure why, by the map of the cow on the Hebrew National website, and their claim of “purer ingredients” using “only the premium cuts from the front half of the cow.”

However, the brand’s kosher certification has generated controversy over the years, initially because production was supervised in house, rather than by an external source. Today Hebrew National is certified kosher by the Triangle K organization, but some glatt kosher Jews still avoid the brand, concerned that the standards are not strict enough.

What’s an Impossible dog made from, anyway?

Here’s what the company’s website says: “Everyone’s favorite questionable food choice has evolved thanks to amazing plants. And it still delivers the meaty, smoky, juicy, delicious flavor you love.”

OK, but what’s in it? The ingredient list says water, wheat gluten, sunflower oil, coconut oil and a bunch of flavorings — garlic, vinegar and “cherry powder” to “promote color retention.”

And how does it taste? I hunted for some comment from Chestnut on that question beyond news of the endorsement, but came up empty. But if they’re selling Impossible dogs in Skowhegan along with Hebrew National when I’m shopping this summer, I’ll give them a try.