The true story behind ‘Call Me By Your Name’ is a profoundly Jewish one

Andre Aciman’s new memoir explores life in a constant diaspora

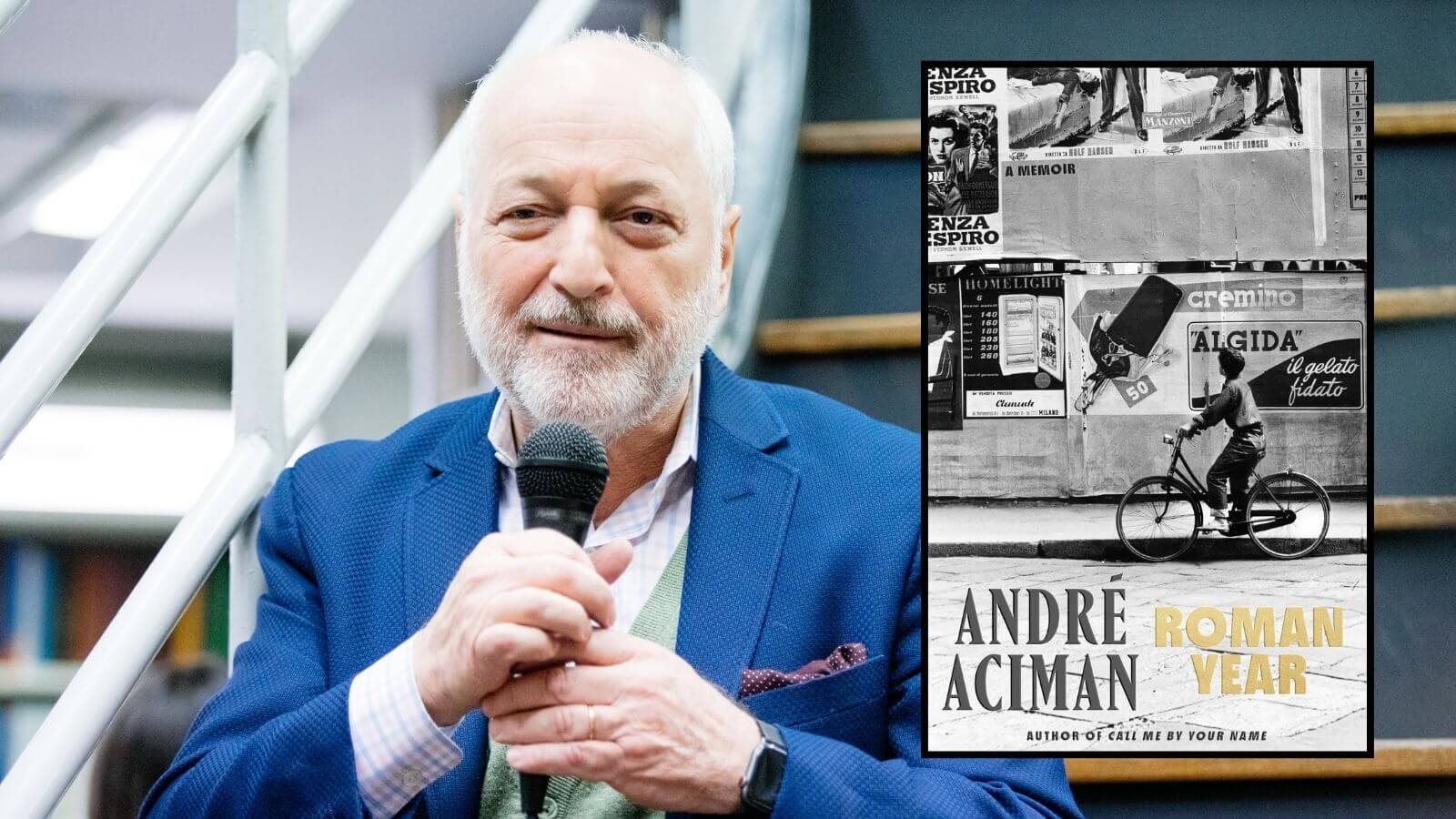

The writer Andre Aciman’s newest book details his first exile, from Alexandria, Egypt, to Rome. Photo by MacMillan Publishers

It’s no secret that Andre Aciman’s novels are a form of autobiography. Like his creator, the narrator of his 2014 novel Harvard Square is a young transplant from Alexandria, Egypt, working toward his doctorate in literature at the titular university. And like Elio, the narrator of Aciman’s hit first novel, Call Me By Your Name, the author is trilingual and spent a year in Italy as a teen.

In his newest book, Roman Year, Aciman brings us the real version of Elio: himself. The memoir wanders through Aciman’s year in the Italian capital, where he arrived in 1965. We get flashes of desperate desire with both men and women. Like Elio, the teenage Aciman uses his obsession with classic authors — Kafka, Dostoevsky, Proust — as a way to reflect on his own life. And like Elio, Aciman speaks Italian, French and English.

Unlike Elio, however, the real Aciman did not reside in a grandiose manor in the countryside; he lived in a small Roman apartment in a shabby neighborhood, where he fled with his mother and brother after their family was evicted from a wealthy life in Alexandria because of their Jewishness.

The book opens as the family arrives in Europe, stepping off a ship from Egypt and into a refugee camp in Naples. Aciman, projecting his own feelings, begins to anthropomorphize their belongings, their only ties to a former life they’d never see again.

“I kept staring at our suitcases and, for the briefest moment, thought that some were even happy to see me again while others turned away, determined to ignore me,” he recalls in the memoir. He wonders if they were upset to be in a foreign country, manhandled by dock workers speaking a Neapolitan dialect that “no suitcase could fathom.”

But before he can meditate further, the uncle who has come to pick up the family from the port scolds him: “No nostalgia, please.”

It’s a useless reminder; nostalgia is Aciman’s basic mode of living. It colors all of his writing and, at least as he remembers his year in Rome today, his everyday life. That wistfulness is what makes Roman Year such a profoundly Jewish book. It’s not because the family is particularly observant — they even celebrate Christmas. No particular moment of plot or story is obviously Jewish; as is the case with much of Aciman’s writing, there’s not much of either. The memoir is more of a meditation — on how one moves through the world without roots, and on how to understand identity in the diaspora. Every line is redolent of the hunger for belonging, coupled with the anticipatory nostalgia of inevitable loss, that has shaped the Jewish experience throughout history.

“I was born in Egypt to a family that continued to idolize the home they’d been forced to leave in Turkey,” Aciman said in an interview conducted by email. “I inherited their nostalgia for Turkey though I had never set a foot there. My family also idolized their alleged home in Spain, of 500 years before, which they fled during the Inquisition. I inherited that as well. Egypt was the only home I knew, and when we were forced to leave, I began to miss it terribly.

“We straddled a no man’s land,” he continued. “We were not French nor Italian, nor Egyptian or Turkish. We were Jewish, but not religious. We didn’t belong to a temple or celebrate the High Holidays with family or friends. We continued to be out of place.”

Even Aciman’s language choices are infused with his placeless identity; throughout the book, he writes full sentences in Italian or French, sometimes even throwing in bits of Arabic, only loosely and partially translating them for the reader. When he meets other Jews, he can identify them by their similarly mixed linguistic choices. At family gatherings, his relatives speak their own dialect, combining every language they’ve encountered throughout their life.

“My relationship with language very much mirrors my relationship with nationality — I’ve never felt like I have a core one. I have many languages, and I speak all of them with the wrong accent,” Aciman said. “I write in English, but my mother tongue is French, but if my mother tongue is French, Italian is the language I usually scribble my notes in.”

In fact, Aciman said, he can never decide anything — what language to use, where home is, even a favorite color feels impossible. “I am not a red person or a blue person; I opt for the spectrum,” he said. “I’m a profoundly divided soul.”

This indecision gives Roman Year a dreamlike quality even as you can almost smell the bergamot wafting through the street markets, or feel the cobblestones underfoot. As a teenager, Aciman deeply resented Rome, and much of the book meanders through his discontented thoughts as much as it wanders the cobblestone streets of the city. It’s only upon leaving for university in the U.S. that he regrets the loss of the city he suddenly realizes he holds dear.

“I was never sure if my love was genuine or simply a product of my own yearnings,” he writes of his feelings for Rome.

Aciman’s struggle to draw a line between ideas and reality is woven into every piece of his writing — down, even, to the tense of the book, in which a sentence that starts from the perspective of the teenage Aciman might finish with an adult reflection.

That might seem like a fault to some; after all, you have to live in the real world for anything to happen in life. But it’s also this quality that makes his work so rich, and so insightful. After all, it’s often from the outside where you can see things most clearly.

“We loved in-between points,” he writes near the end of the book. Jews rarely have the luxury of loving anything else.