100 years after its founding, can a Yiddish institute serve a people who don’t speak the language?

YIVO’s centennial marks a fractious time in Jewish life. It’s ready for the challenge.

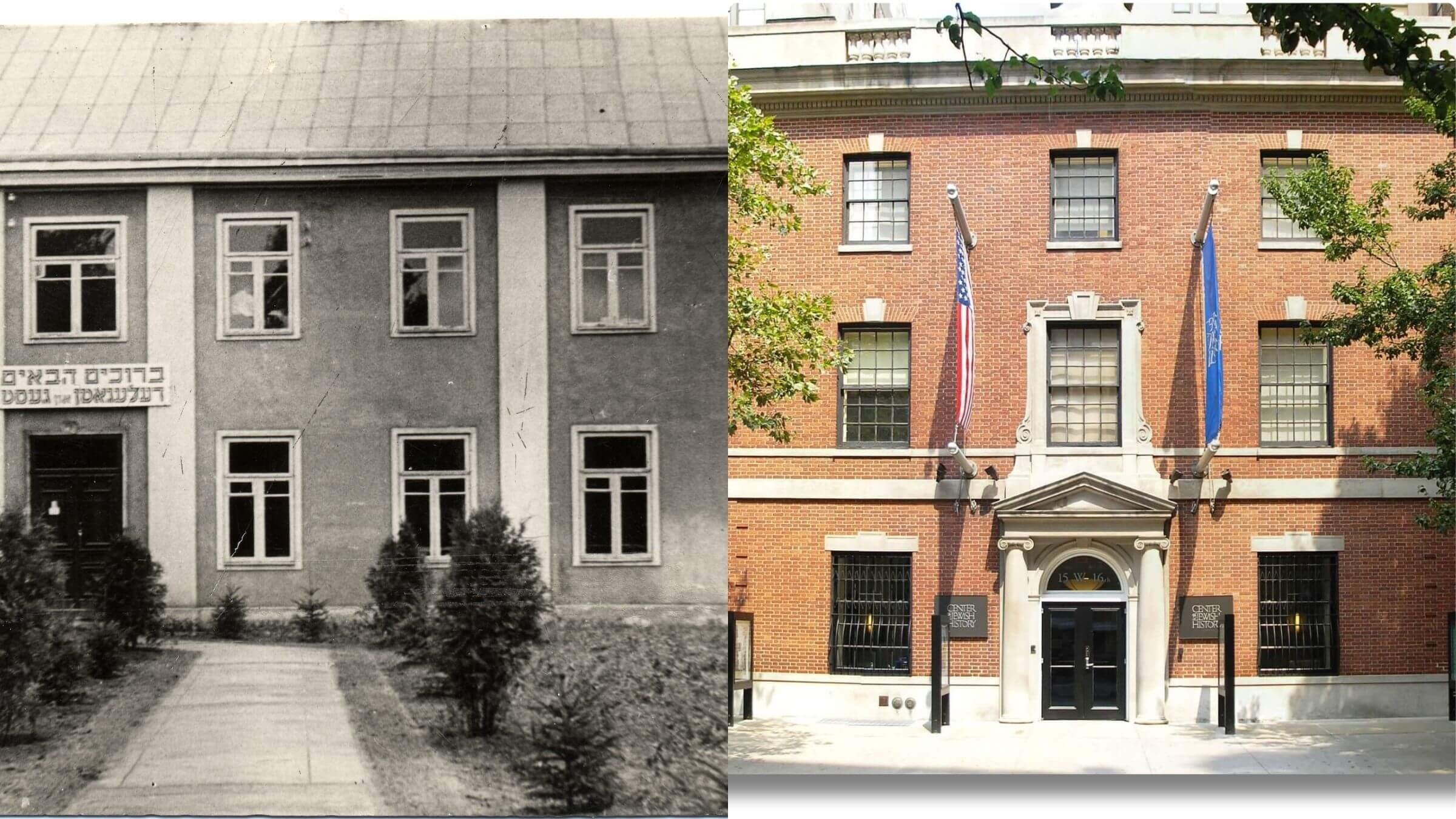

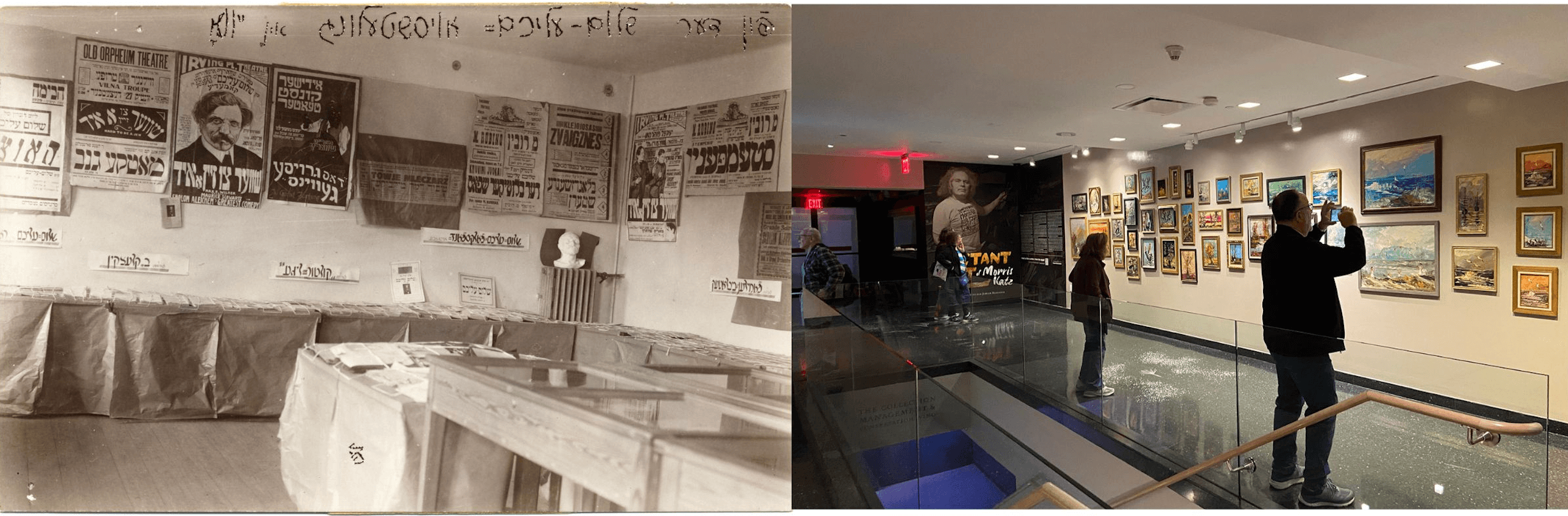

The YIVO building in Vilna, left, and its new home near Union Square, right, tell a story of assimilation and the struggle for continuity. Photo by YIVO Archives/Gryffindor/Wikimedia Commons

The YIVO institute, an archive, library and research institution on Eastern European Jewish civilization, recently stumbled on a novel problem in its 100 year history.

In its early days in Europe, the Institute for Jewish Research was the first organization to seriously undertake a standardization of Yiddish spelling. It survived World War II — with some of its staff smuggling its artifacts back to the Vilna ghetto. In America its scholars helped create the field of Jewish studies and launch the klezmer revival. It lived to see the reunification of its collection with the collapse of the Soviet Union. But it had seldom encountered a very late-20th-century issue: Wingdings.

“Do you think I should throw it out?” asked Jessica Podhorcer, a project archivist, in her corner of the third-floor warren of desks, side rooms and gray, carbon-free boxes where millions of documents were being sorted.

She was processing a 1999 web forum for a reunion of Camp Hemshekh, a Holocaust survivor-founded camp in upstate New York that shuttered in 1978. Whole pages of it were in the nonsense, dingbat font of Wingdings — a Space Invaders-like glyph here, a proto emoji there.

“I think this is not useful,” said Stefanie Halpern, director of the YIVO archives. Behind her, the head of archival processing was in his office, crammed with stacked cardboard containers and their contents, including a Yiddish edition of the Forverts from 1970.

Podhorcer, a child of the 1990s, was feeling nostalgic about a camp that closed 15 years before she was born. The website was no longer online. YIVO’s mission would seem to dictate that most everything gets saved, from its earliest days when zamlers (collectors) set out to keep a record of a Jewish world hurtling towards modernity. But there are no clear guidelines for whether or not to hold onto papers filled with glyphs that don’t mean anything.

“Most of our collections that we have done collectively have not reached the 1990s,” Halpern told me. As YIVO’s holdings continue to grow, “you will come into contact more and more with this kind of stuff.”

Even Wingdings could tell a future audience how Jews once lived.

An institute for the folk

YIVO, which turns 100 this month, is forever associated with Vilna (modern day Vilnius, Lithuania) and Eastern Europe, but it was originally supposed to be based in Berlin.

The idea for the institute came at a unique inflection point in history. After World War I, diaspora nationalist movements anticipated new government resources from minority treaties, international agreements granting rights to minority populations in countries looking to join the League of Nations. There was an urgency to documenting a way of life that seemed to be fading.

“The First World War really had a huge impact in the level of destruction in the areas of densest Jewish settlement in the world, which were the Yiddish-speaking communities in Eastern Europe,” Cecile Kuznitz, author of YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture: Scholarship for the Yiddish Nation, told me. “And it gave a strong push to the movements that were trying to preserve elements of Jewish culture and make sure that there were places where books and documents could be safeguarded and history could be recorded.”

It was Nokhem Shtif, a fanatical scholar from Rovno (now Rivne, in Western Ukraine), who first proposed an institute for Jewish research in an October 1924 memorandum. Shtif had his own urgent reasons: He was broke, and Jewish organizations regularly refused his requests for honorariums.

Shtif believed wealthier, intellectual Jews in Berlin, where he was then based, would support a Yiddish institute and library.

“There arrives the time when every people at a certain level of cultural development must and wishes to participate directly in the scholarly work of the entire intellectual world,” Shtif contended in his memorandum, arguing the time for Jews was now.

German Jews didn’t give Shtif the reception he’d hoped for, but on March 24 of the following year, a group of more than 30 people, most with connections to the thriving Yiddish secular school network, met in Vilna, then a part of Poland, to discuss Shtif’s proposal.

They approved it, forming a committee to realize the project. Max Weinreich, who would emerge as the driving force of YIVO in its early days in its ultimate home in Vilna and later in New York, said Shtif’s vision of YIVO “was born in his mind as a plan to raise the importance of the Yiddish language, which means in effect the respect of the Jew for himself and his faith in himself, his confidence.”

YIVO’s patronage soon grew beyond scholarly circles to a genuine “movement of the folk,” as one press account called it.

In a January 1926 publication, YIVO’s ethnographic commission reached out to its supporters, enjoining those in cities and shtetls to collect a record of their heritage. “Wherever the Yiddish language lives, wherever the Yiddish song rings out, wherever Yiddish stories are still told and Yiddish customs are not yet pushed aside, there are scattered the treasures of our folk creativity. Don’t let them be lost!”

The act of zamling (gathering) involved the larger Jewish community, with many of those who took up the task of collecting folklore and songs being so poor they asked YIVO for postage. While YIVO received support from relatively better off Americans (YIVO’s American branch, the Amopteyl, was also incorporated in 1925), the majority of those who donated to support its mission didn’t have much to give.

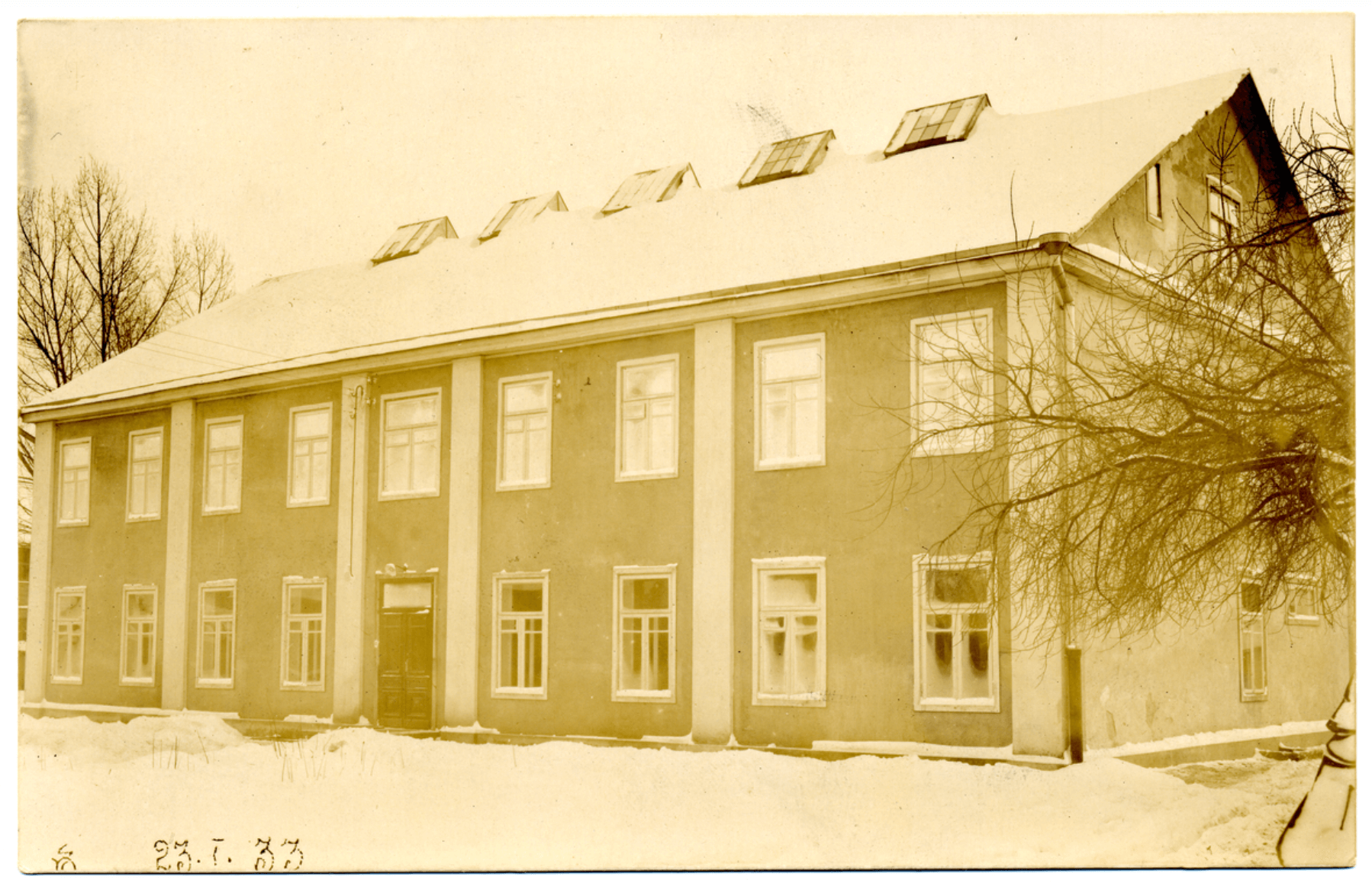

In 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression and following a large period of fundraising, YIVO laid a cornerstone for its headquarters on Vilna’s Wiwulskiego Street, accompanied by an orchestra and school children waving flags.

“Although it is apparently as poor as a little house in one of my paintings, it is however at the same time as rich as the Temple,” Marc Chagall said of the building some years later.

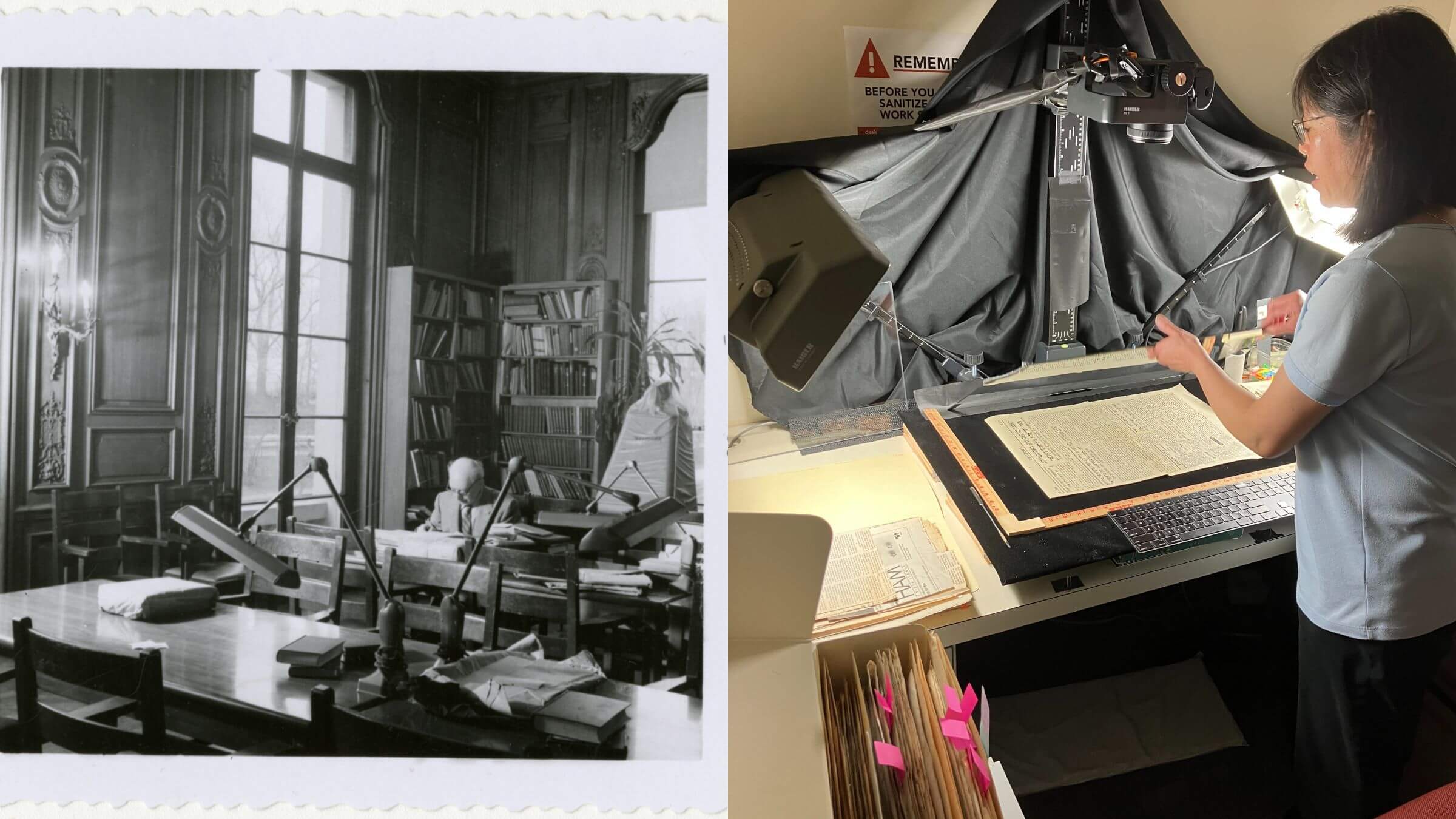

Historian Lucy Dawidowicz, who was born in America but came to Vilna in 1938 to work at YIVO as a research fellow, marveled at the giant vestibule, the seats in the reading room, all with their own fluorescent lamps (a feature libraries in New York didn’t have). Others remarked on the landscaping and flowerbeds and the lively scene of everyone from schoolgirls to labor activists coming to work and learn.

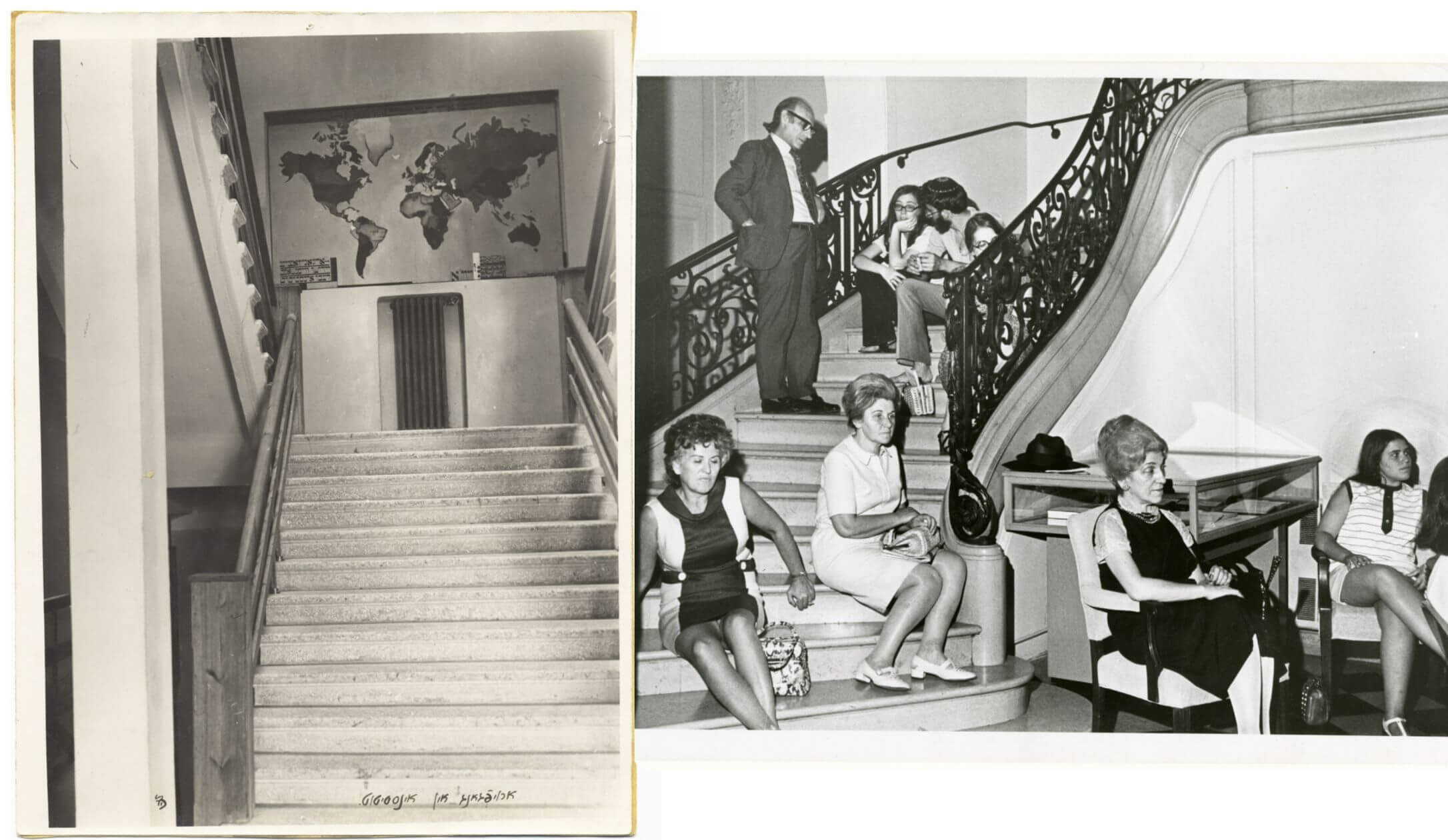

A manuscript quoted in Kuznitz’s book makes mention of the broad stairs, over which stood a map of the world, with pins indicating YIVO’s branches in Berlin, New York and Buenos Aires, staking its claim as an institution for a scattered people.

When World War II broke out in 1939, Max Weinreich was in Denmark. He fled to New York, and, while many of his colleagues and the vast majority of the institute’s collection were stuck in Vilna, YIVO relocated with him.

An East European transplant, at home in New York

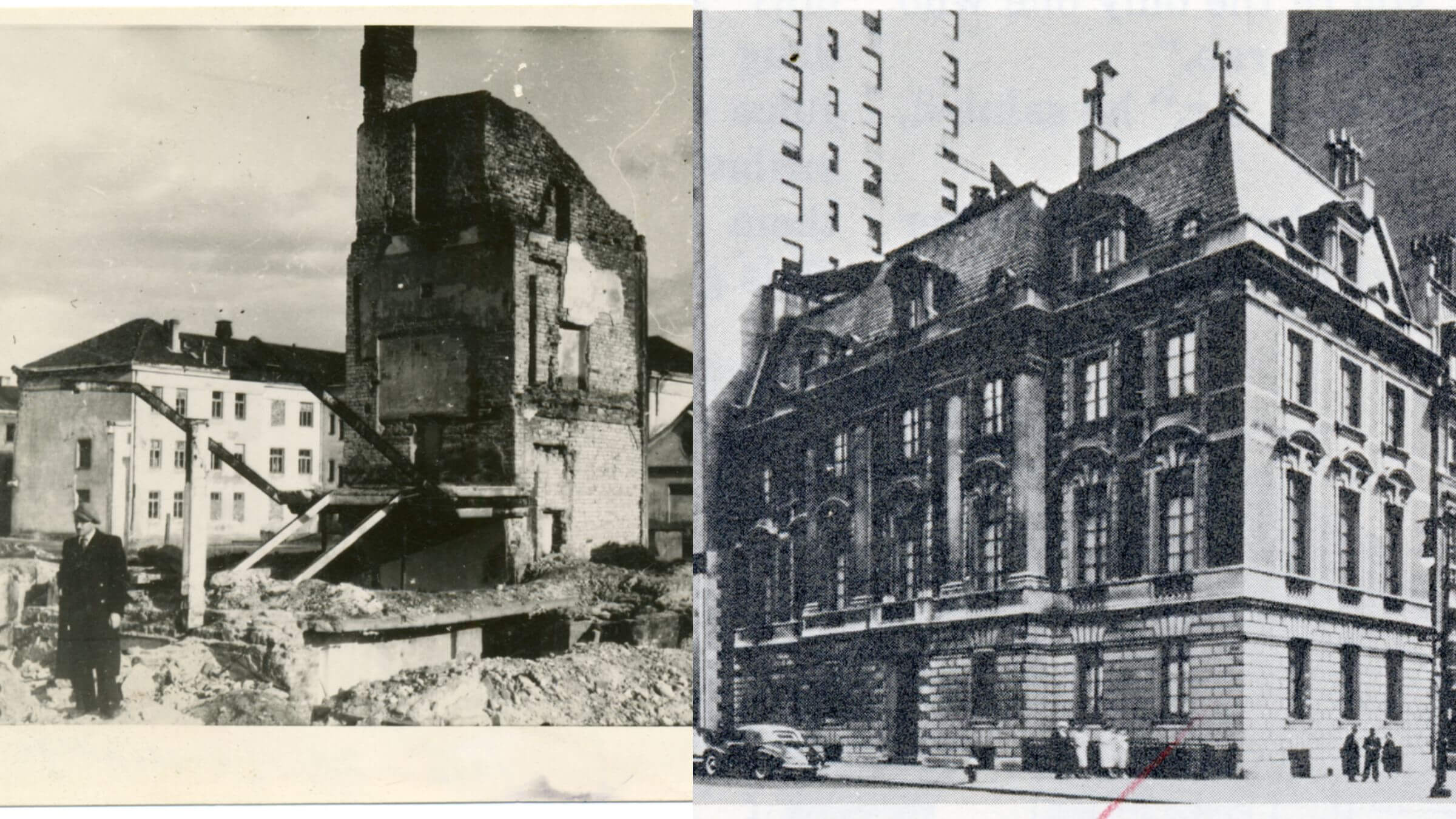

When the Nazis occupied Vilna in June 1941, they commandeered the YIVO building, and began their own collecting.

20 Jewish forced laborers were made to sort through the Institute’s holdings, which were to be sent to Frankfurt’s Institute for Research on the Jewish Question, devised for the study of a culture the Third Reich sought to exterminate.

The workers, known as the Paper Brigade, smuggled documents back to the Vilna ghetto and continued to collect new artifacts from their time under Nazi occupation. Their dramatic story will be a part of YIVO’s centennial exhibition in New York.

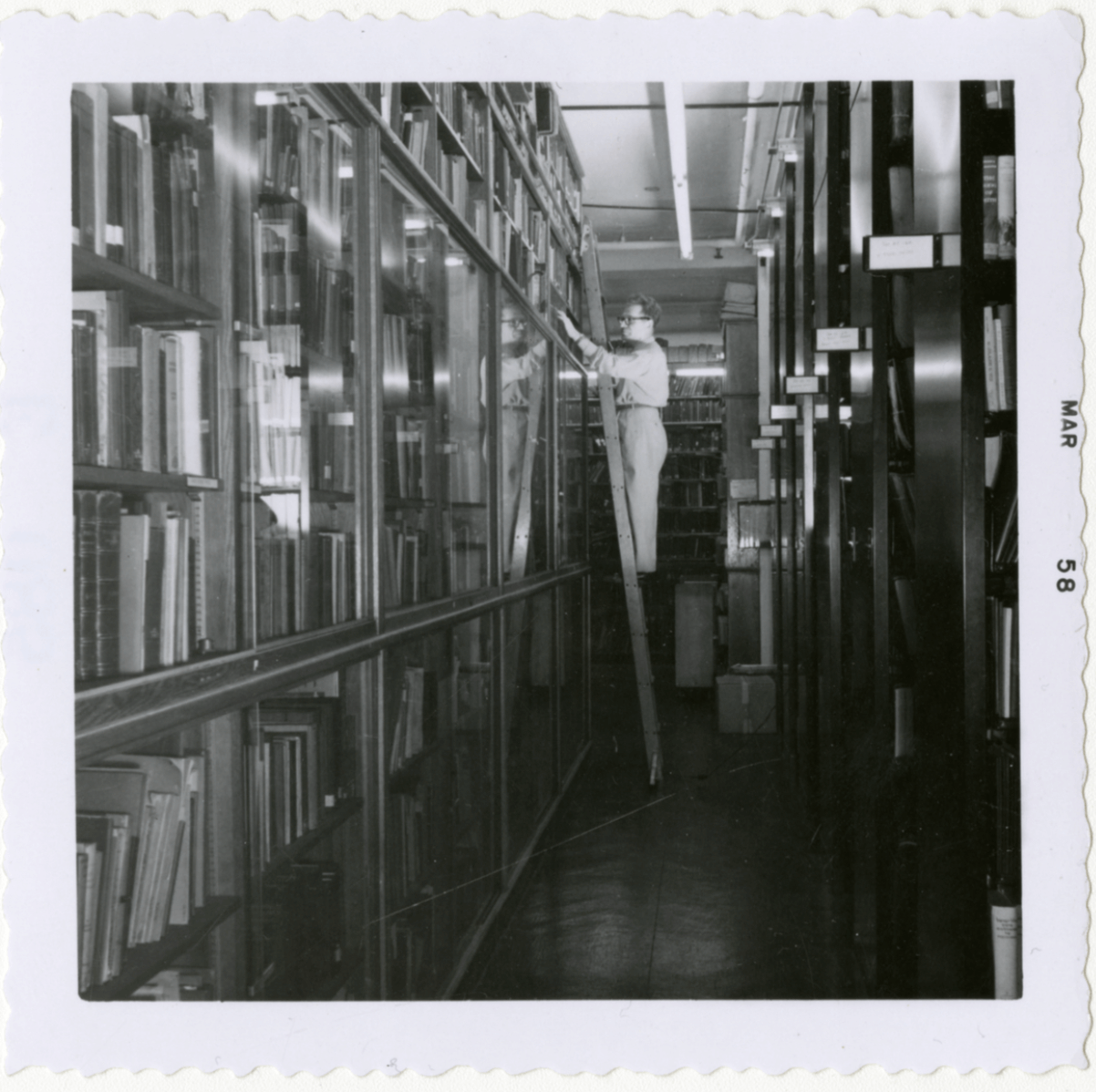

YIVO had several homes in its early days in the United States. The library, originally that of the Central Jewish Library, was first located in the HIAS building on Lafayette Street, in what is now the Public Theatre. In 1944, the institute relocated to a townhouse on West 123rd Street. By 1955, YIVO — which officially adopted an English name as the Institute for Jewish Research — was based in a former Vanderbilt mansion on East 86th Street and Fifth Avenue, facing Central Park.

“It was this Vanderbilt mansion on the one hand, and this East European transplant, from another universe, from another world,” said Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Jewish studies scholar and curator of the core exhibition at the POLIN Jewish museum in Warsaw.

The lights were dim, and she half expected the heat to be turned off.

YIVO was then staffed by refugees — those who escaped before World War II or who survived the Holocaust. The secretaries, translators and typists were often Hasidic women from Brooklyn.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett arrived in 1967 as a Ph.D. student, in time to have tea with Weinreich — by then blind — and meet some of the founding generation. (Weinreich died in 1969, a few years before the publication of his four volume History of the Yiddish Language.)

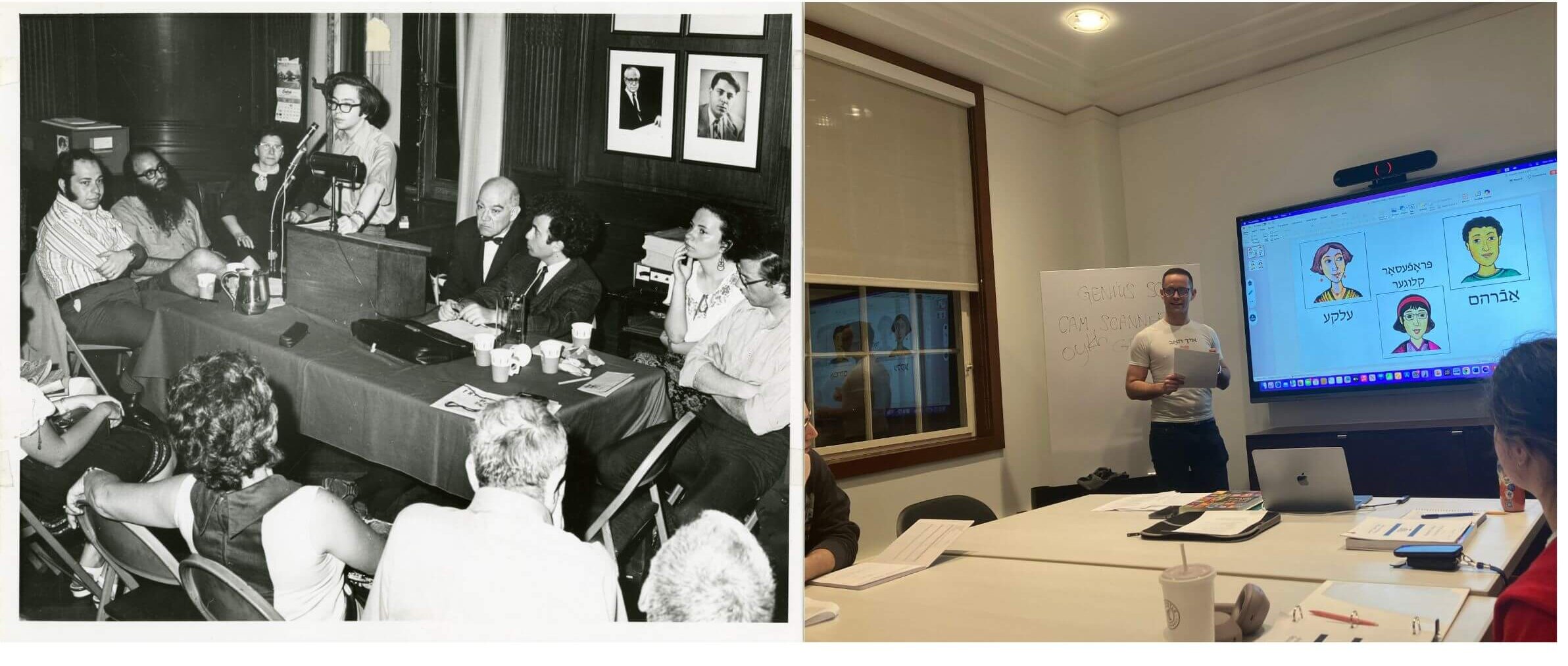

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett returned in 1972 to teach at the Max Weinreich Center for Advanced Jewish Studies, a YIVO program founded in 1968, a year before the Association of Jewish Studies gave such research more legitimacy in the academy. In its early years, the Weinreich Center launched legendary cohorts of young scholars who would go on to advance the field. As YIVO continued its work, it amassed private libraries, becoming what one former staff member called a “collection of collections.”

Zachary Baker, former head librarian of YIVO, started as a student in the Yiddish summer program and joined the staff in the late 1970s. He was there when they moved the archive in 1994 to an office building on 57th Street. (On the ground floor was a Ford showroom — Geraldo Rivera kept an office in the building.)

Baker, who hails from Minnesota, remembers feeling like he was among the “last of the Mohicans” working alongside American-born employees in their 20s and 30s and European-born administrators, custodians, and scholars in their 60s and beyond. Viewing YIVO and its young staff today, he said, “maybe we weren’t the last of the Mohicans. Maybe we were the first.”

By 1999, when Baker left YIVO to curate the Judaica and Hebraica collection at Stanford University, the institute had relocated to its current home at the Center for Jewish History on 16th Street near Union Square. It shares the building with other Jewish organizations like the American Jewish Historical Society and the Leo Baeck Institute. The immediate impression on entering is one of affluence, with a coat check, metal detectors and a terrazzo floor with details of the biblical Seven Species.

“It’s on a completely incomparable, unimaginable scale, compared to what we began with in 1940, and certainly compared to Vilna,” said Kalman Weiser, author of a forthcoming book on YIVO’s New York years.

“YIVO has become, I think, an institute that resembles its constituency,” Weiser said. “Its constituency are middle class, if not upper-middle class, American Jews of Yiddish-speaking origin. And that’s largely what YIVO looks like today.”

“It’s a folk organization in search of a folk, and I think it’s found its folk,” Weiser added. “Or rather, the folk found its way back to it.”

An intellectual home — but for who?

When YIVO approached Jonathan Brent, a publisher and historian who spent years studying in the Stalin archives, as a candidate to lead the institute, he said he didn’t want to take the meeting.

“I was afraid it was going to be like going to my grandmother’s closet and looking through her hat boxes,” Brent said.

He came in for the meeting anyway. At one point, quietly, the then-head of the archive handed him a copy of the Guide to the YIVO Archives, a catalogue of the institute’s holdings.

Paging through it, he saw there were over 700 linear feet devoted to the General Jewish Labor Bund, the Jewish labor movement begun in Europe in 1897. He’d been studying that group. Then he saw the archive of Sholem Schwarzbard, the Russian-French Yiddish poet. He taught about Schwarzbard in his class at Bard College. There were letters from Thomas Mann, Leo Tolstoy and Leon Trotsky.

“I said to myself, ‘This is the place for me, intellectually,’” said Brent, who has served as executive director and CEO of YIVO since 2009.

“It’s a folk organization in search of a folk, and I think it’s found its folk. Or rather, the folk found its way back to it.”Kalman WeiserHistorian of YIVO

When I spoke with Brent, first on Zoom and then in his office at YIVO, it was about a year after a controversy for the institute.

In March 2024, Brent, with Jeffrey Herf, a professor emeritus of the University of Maryland, dedicated a Zoom lecture series to Hamas, linking its ideology to Nazi and Soviet antisemitism.

The secular Yiddish world’s makeup includes many critical of Israel’s prosecution of the war in Gaza or who identify as anti-Zionists. They voiced their outrage on an Instagram post announcing the series, accusing YIVO of advancing right-wing Israeli talking points. Many felt that YIVO, an institute perceived as being committed primarily to Yiddish scholarship, had betrayed its mission to preserve and study Jewish culture and had instead become political.

Poet and activist Irena Klepfisz, a lifelong supporter of YIVO whose mother worked there in the 1950s, stressed in a January 2025 interview that she was not out to boycott the institute. She was, however, upset by the lecture series, believing it to be intellectually “shoddy” for failing to not also consider Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his extremist fellow travelers.

“A place like YIVO should be teaching us how to tell these stories fully,” Klepfisz said. “You have to learn the complexity of things. And I think YIVO abdicated that role as an educational institution. And I’m sorry to see that.”

Yael Horowitz, a student in the YIVO summer program in 2023, who uses YIVO’s archives for their doctoral thesis, objected to the institute’s messaging after Oct. 7, but said that they will continue to use their resources.

“The archive and this history belongs to all of us,” Horowitz said. “It’s mine as much as it is theirs. They should be stewards of the archive, not owners of it.”

Horowitz finds it disappointing that they don’t feel “institutional support” from YIVO, and believes its position of seeming to defend Israel is “not where the future of Yiddish culture lies.” (Others I spoke with for an article on the controversy cancelled plans to participate in YIVO classes.)

Many critics are quick to note that YIVO originally emerged from an alternative nationalist movement to Zionism, focused on the Jewish diaspora over nation building, a philosophy represented most notably by the Bund.

Brent maintains that YIVO is staying true to what one of its founders, Arcadius Kahan, called “glorious indifference,” and that the archive, which represents the totality of Jewish experience, is even more essential now given the “splintering of Jewish life.”

A much bigger story

YIVO has had controversies in the past.

In its early years in Vilna, YIVO resisted pressure from Marxists and Bundists to take on an explicitly political position. An uproar over adopting phonetic spelling of Hebrew and Aramaic words in Yiddish nearly derailed its annual conference in 1931, with debates lasting seven hours.

After the war, Weiser said, the question of accepting reparations from Nazi Germany was a third rail topic, and at least one board member resigned over the outrage when YIVO took the money. There were controversies over the institute’s position on pro-Soviet Yiddish institutions and accusations that YIVO was too concerned with American interests or appealing to American youth.

In January 2020, citing a budget shortfall, YIVO laid off its library staff, prompting a letter signed by nearly 700 scholars, students and former employees condemning the personnel cuts. (A board member, Karen Underhill, resigned.)

Brent said he isn’t worried about losing the critics of his Hamas lecture, or a recent online talk with author Adam Kirsch about how Israel doesn’t meet the standard of “settler-colonialism.”

“Part of YIVO’s responsibility is to help people grow up,” Brent said, “because we can offer people a context of knowledge, knowledge that’s based on a deep understanding of history through these materials, actual materials, where they can see how, for instance, 10 different ideologies coexisted in the same shtetl in the same town.”

“People change,” Brent added, “and we can see that change in the materials that we have in our archives.”

Brent told a story about how Philip Roth, who wanted little to do with YIVO, read its two-volume Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, which Brent sent as a thank you for doing a reading of his final novel, Nemesis, at YIVO.

“He said, ‘You know, I used to think I was born in Newark, and now I realize it’s a much bigger story.’”

Bigger than Yiddish

When YIVO began, Kuznitz writes in her book, its vision was to elevate Yiddish from a “lowly ‘jargon’” to a modern language with the scholarly prestige of any other European tongue, “a fitting vehicle for a sophisticated high culture.”

In many ways, the YIVO of today faces an inversion of this dilemma. Most Jews outside of the Haredi world don’t speak Yiddish, and the group that does is now largely an academic and activist crowd known as Yiddishists. Echoing this change, much of the Yiddish flavor of YIVO has disappeared.

Weiser, the historian of YIVO in America, said scholars no longer fill out their requests in the reading room in Yiddish — and, he added wryly, everyone who requests materials is now treated equally. Much of YIVO’s programing, even an exhibit on Yiddish typewriters and Yiddish in Mandatory Palestine, had wall text in English. But YIVO was never solely an archive of Yiddish.

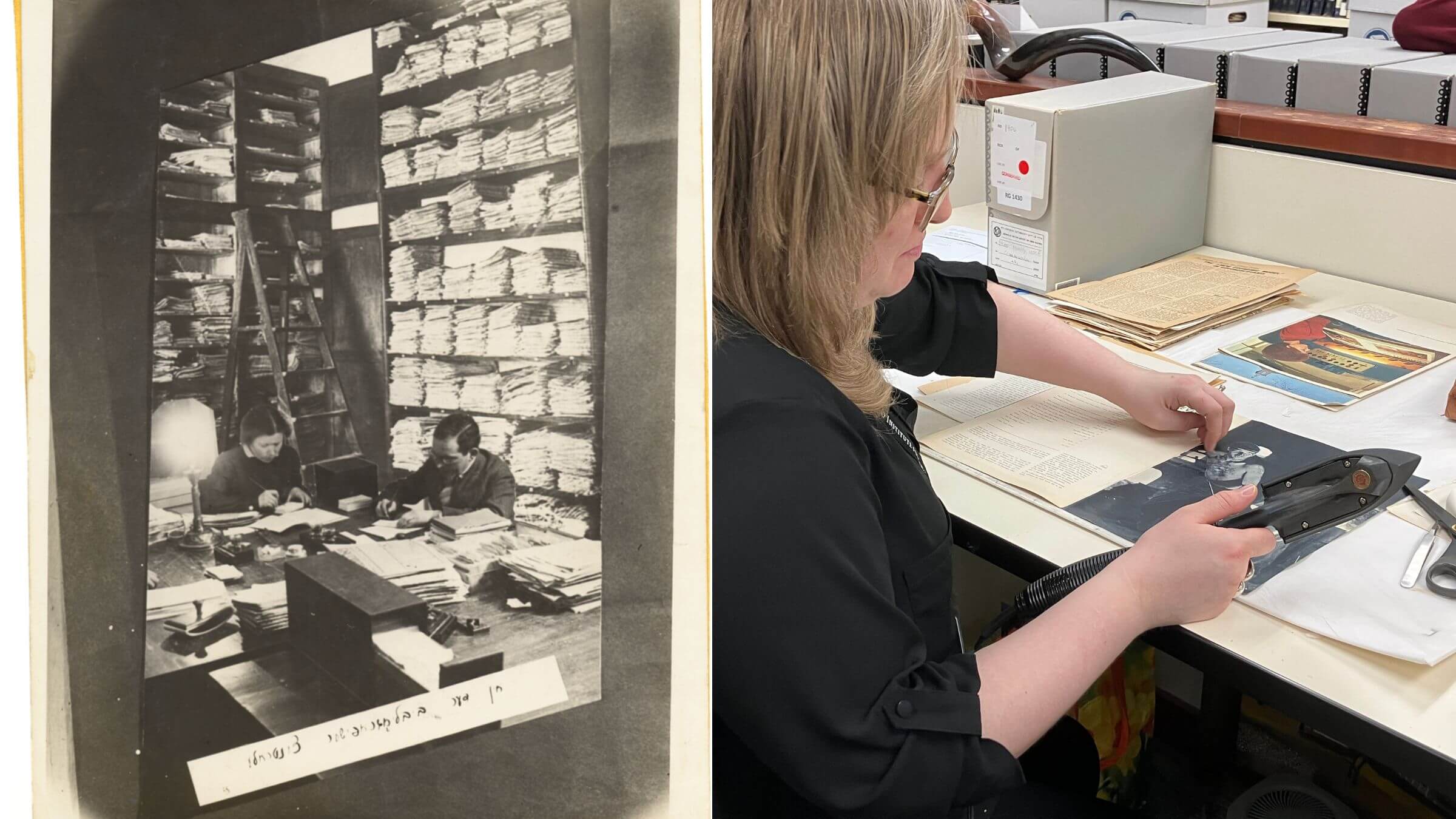

Following the digitization of the Vilna Collection, which consolidated YIVO’s holdings with some 170,000 documents discovered in Vilnius in 2017, the institute is busy digitizing 3.5 million artifacts from the collection of the Bund.

Recently, during his daily work, Yakov Sklar, head of archival processing, found a book, in English, on the 16 Soviet Republics.

Growing up in what is now Ukraine, then the Soviet Union, Sklar had only heard of 15 republics. This book named Finland as the 16th; during World War II, the country lost a considerable portion of its territory to the Soviet Union. This detail from the past tells us something about Russian expansionism today.

“It’s happening again now in Ukraine,” Sklar said in his office on the third floor, which, due to his workflow, could be mistaken as a set from Hoarders, if the hoarder in question happened to be particularly interested in Communism and labor. “We never learned our lessons from history, so that’s why we’re experiencing this again.”

The Bund archive consists of five or six languages — Sklar knows Ukrainian and Russian and relies on colleagues for Yiddish. While YIVO at first concentrated on advancing Yiddish, Sklar said, it’s since expanded, showing that Yiddish-speaking Jews were always in dialogue with the wider world.

Down a hall, lined with sepia-toned images and mezuzahs on doorposts, is a space devoted to preservation.

On the afternoon I visited, conservator Allison Richards, working on an elevated table, checked for damage on a magazine from the Confederation of Free German Trade Unions (in English) and an English propaganda brochure from North Korea. Opposite her, a colleague examined newspaper articles on Leon Trotsky.

In a dark room Judi Yuen, a digital projects specialist, took photos of articles about the trial of John Demjanjuk, accused of being the Nazi guard Ivan the Terrible, with a DSLR camera suspended on a metal arm.

Brent is hopeful that the Bund archive’s massive digitization initiative will revolutionize areas of scholarship that go beyond Jewish studies. (For translating, they’re looking into AI models that can handle Yiddish cursive, notoriously difficult to make out even for many humans.)

In his office, Brent was eager to show me images from the Vernadsky Library in Ukraine, artifacts from the author S. Ansky’s expeditions to shtetls in the 1910s. Brent recently went to wartime Ukraine through Warsaw on an 18-hour drive with YIVO’s chief of staff, Shelly Freeman, to view the collection, which they plan to help digitize. While the artifacts will remain in the library, the goal is to have them accessible for everyone with an internet connection.

Among the highlights were a mizrah, a decorative wall hanging, featuring the Russian imperial eagle, and a page from an 18th-century Haggadah, which shows Joseph’s pallbearers in Hasidic attire. Both show how Jews were thinking of themselves, and how, under the Tsar, they held on to their tradition while incorporating the broader culture of their surroundings.

“It will open up an understanding of how Jews were adapting, how Jews were assimilating this into their tradition of which we are the inheritors,” Brent said.

YIVO for the youth?

YIVO events, including an exhibit on the chosen people and cannabis, draw a mixed crowd.

Many attendees have gray hair, some wear kippot. One recent Tuesday, a group of young people, hair various shades of Manic Panic, was visiting. They were students from the New School contributing to an oral history project about Jewish life amid the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

During the pandemic, YIVO’s online courses, which started before the whole world pivoted to Zoom, saw a huge uptick that’s kept pace since with classes on Jewish comedy, folk song and Yiddish language.

Ben Kaplan, YIVO’s director of education, and Dovid Braun, academic advisor in Yiddish language, pedagogy and linguistics, say there isn’t a typical Yiddish student.

“There’s like a 70-year age range between the youngest and oldest student,” Kaplan said.

Recent pupils include a retired ER doctor (now translating the prose work of Yiddish poet Itzik Manger), an astrophysicist, and an undergrad from China. At the end of his course, the Chinese student presented scholarship that showed Chinese intellectuals, looking to standardize their language in the early 20th century, were aware of Yiddishists’ efforts in Eastern Europe at the same time.

“It took someone who was fluent in Chinese to come study Yiddish to figure this out,” said Braun.

While online and in-person classes have seen growth, Alex Weiser (no relation to Kalman Weiser), YIVO’s director of public programming, has been busy preparing the institute’s new learning and media center, set to open in May.

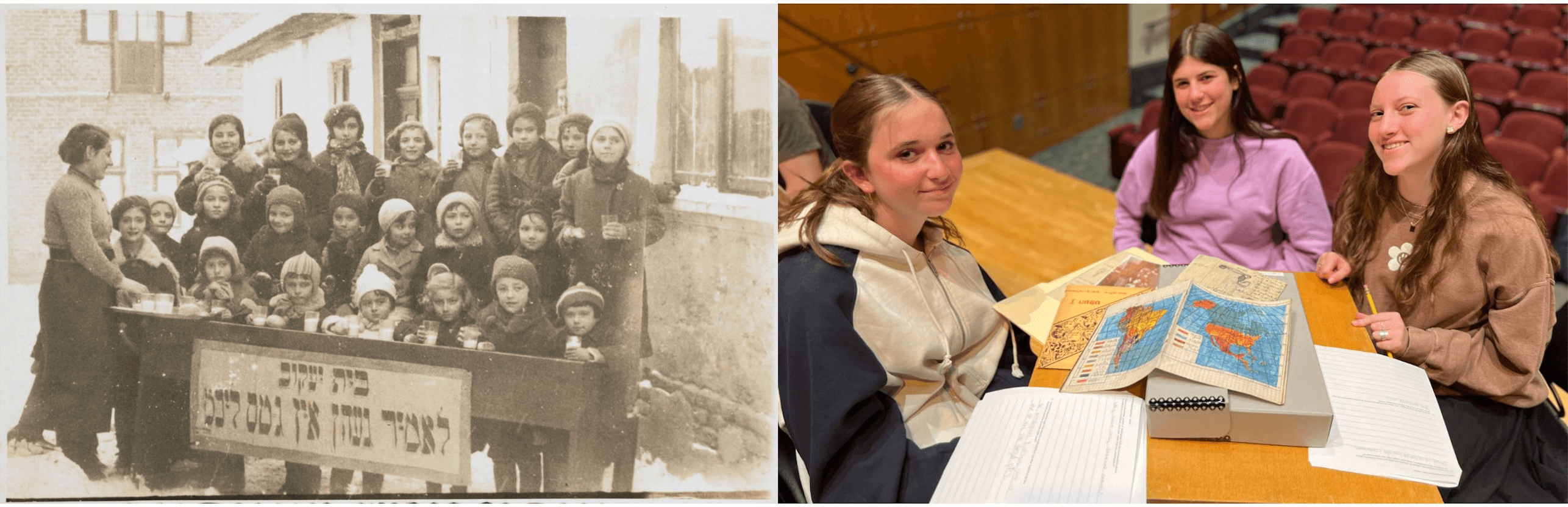

In it, middle and high schoolers will have a chance to look through archival boxes, with museum-quality reproductions of material in the archives, including autobiographies penned by children for a YIVO contest nearly 100 years ago. Among the artifacts is a picture of young girls outside their Bais Yaakov school, holding glasses of milk.

Seeing these items, Weiser believes, will lead to an “aha moment,” where young people who may not have been brought up to learn Yiddish, will realize that in the time of their great-grandparents, children lived similar lives.

‘I should learn more words’

At a Monday night introductory Yiddish class, instructor Moishele Alfonso — originally from Tennessee and a former employee of the Yiddish Forward — let students know about an app they can use to submit homework as a PDF. Wearing a CafePress custom shirt reading “I heart Yiddish” in the alef-beys, Alfonso guided a class of 13 through greetings and introductions.

The students took turns describing their gegnt (neighborhood). They come from Manhattanville, Brooklyn Heights, Midtown, Bushwick, Williamsburg and the East Village and live in internatin (dorms), dires (apartments) and hayzer (homes).

Among the learners were a mother and daughter, college students, an employee for the New York State Assembly, and Edna Teich, a 79-year-old born in postwar Poland to Yiddish-speaking parents.

“I’m an alte bobeh,” Teich said. She was surprised how young the rest of her classmates were.

Yiddish class in the 21st century means learning “zey” as a personal nonbinary pronoun and practicing Yiddish cursive on a smart board. Virtual classes and seminars span the globe. Some students come because they are interested in languages; others are grad students who need to know Yiddish for their research.

Isabella Newman, 34, was inspired to learn by new arrivals in her life.

“A lot of my friends have been having babies and when I go to meet the babies, and I’m holding the babies, Yiddish comes out of me,” Newman said.

“I say, like, ‘Oh your little kepi. Oh your henties’ to the baby. And I was like, ‘Where’s that coming from?’”

In the end, she concluded it must have come from hearing her grandparents when she was a baby.

“I guess I was doing some kind of mirroring and I thought I should learn more words,” Newman said.

Max Weinreich wrote in 1958 that, “as long as the world exists, there will always be Jews who want to understand their roots in order to thereby understand themselves.” His prediction is proving correct. 100 years on, YIVO is there for them.

As for any Wingdings? A decision has yet to be made on their fate.

Corrections: A previous version of this article misnamed the book Jonathan Brent was handed. It was The Guide to the YIVO Archives, not the YIVO Encyclopedia. The article also initially misstated Camp Hemshekh’s affiliation. While many of its founders were Bundists, not all were, and it was not officially affiliated with the General Jewish Labor Bund. Also, the YIVO board member who resigned in 2020 was Karen Underhill, not Lyudmila Sholokhova, who was a librarian and not a board member.