An unprecedented, and unfinished work, of Yiddish scholarship is now an opera

‘The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language’ chronicles a quest to save a forgotten world

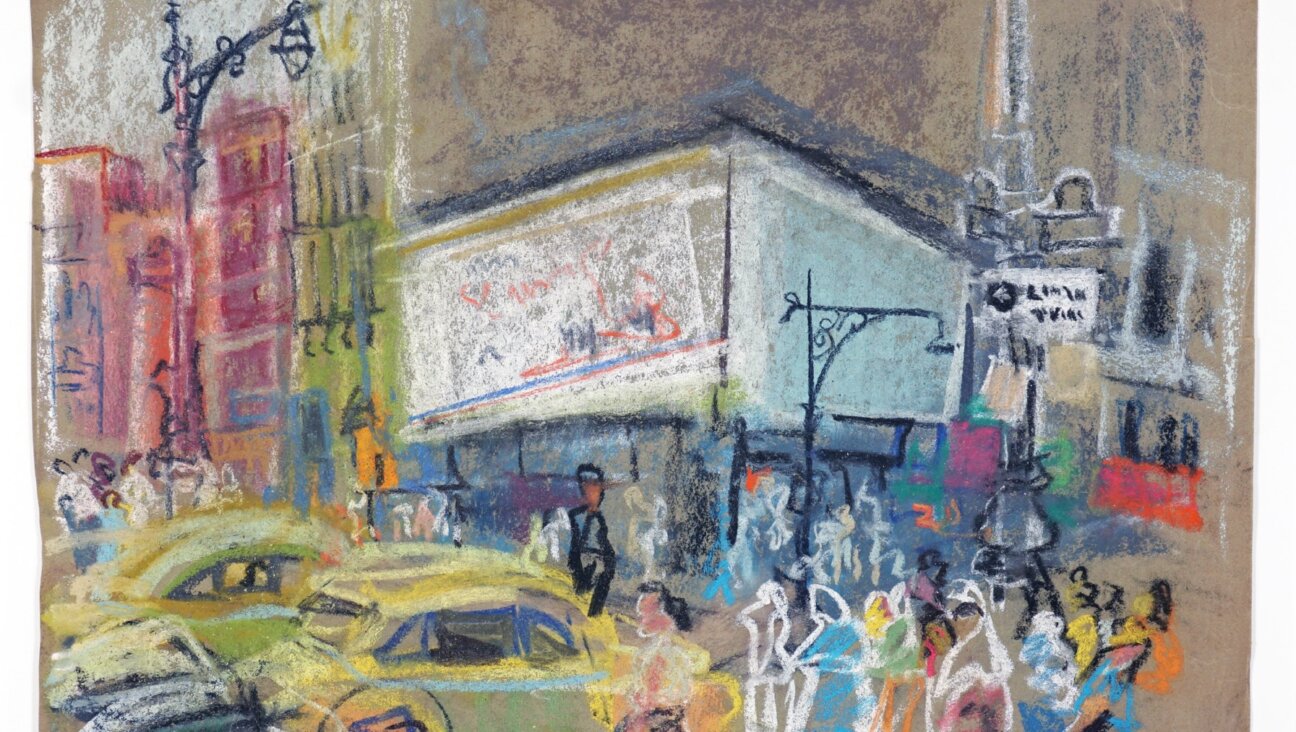

Gideon Dabi as Max Weinreich and Jason Weisinger as Yudel Mark in Alex Weiser and Ben Kaplan’s The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language. Courtesy of The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

Sign up for Forwarding the News, our essential morning briefing with trusted, nonpartisan news and analysis, curated by Senior Writer Benyamin Cohen.

When Ben Kaplan and Alex Weiser started working at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, they heard one of its essential legends in the form of a joke.

The 100-year-old library and archive, whose holdings date back centuries and are filled with countless artifacts of Yiddish life that barely escaped the Shoah, once endeavored to create an academic dictionary of the Yiddish language. The punchline? They couldn’t get past aleph.

“It’s a kind of version of the two Jews, three opinions, kind of joke,” said Weiser, a Pulitzer-prize finalist composer and YIVO’s director of public programs.

When Weiser learned his former YIVO colleague Leyzer Burko’s dissertation at the Jewish Theological Seminary featured a chapter on the unfinished dictionary, he was eager to read it.

What he found explained some of the gridlock. Heading the project was the linguist and educator Yudel Mark, who saw the task of completing a dictionary as holy work. Undertaking the project in New York in the aftermath of the Holocaust, Mark saw himself rescuing the words of an exterminated civilization. They weren’t merely words to him, but “sparks” of the divine.

But in Mark’s desire to be comprehensive — including the argot of thieves, tradesmen and children — the undertaking became untenable.

The project wasn’t only too large; it was a fight for the soul of Yiddish. Max Weinreich, the head of YIVO, had made his life’s work standardizing Yiddish spelling and grammar; he resisted Mark’s draft for deviating from those principles, called the takones. The debates over these spelling conventions created factions and led to hourlong shouting matches that would often stretch well into the night.

Reading Burko’s account, Weiser thought it had the makings of an opera, and took the idea to Kaplan, YIVO’s director of education, as well as to a librettist with whom he’d previously worked on an opera about Theodor Herzl. Kaplan thought he was indulging Weiser, but quickly saw the story’s dramatic potential.

“It wasn’t just about a dictionary,” Kaplan said “It was about grief. It was about postwar Jewish life. It was about what you have to leave behind that you can’t take with you. What do you choose to save?”

The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language, Weiser and Kaplan’s chamber opera, which is mounting its first full production Sept. 18 at the Center for Jewish History, dramatizes the postwar debates, bounding between Marks’ cramped office and the mystical sphere of a language driven to near extinction by genocide.

The show opens with Mark (played by tenor Jason Weisinger) resting his head on a book. From this hard pillow, he, like Jacob the patriarch, receives a vision. Not a ladder, but the three alephs of the Yiddish language, mezzo sopranos who appear in a heterophonic roar of sound.

“Veln zey lebn,” they say — will they live?

They are referring to dried up Yiddish words, which stretch out before Mark on a barren landscape like the valley of bones glimpsed by Ezekiel. The Shtumer, Komets and Pasekh task him to speak to the words, breathe them, fill them with life and efn zeyere kvorim — open their graves.

The action then follows Mark’s showdown with Weinreich, and his efforts, in Israel, to finish the work. He never did get past aleph, but he estimated he saved over 200,000 words. While he falls short in his mission — imagined at 10 or 12 volumes — he is reassured by the Shtumer Aleph, traditionally a silent letter, here speaking for a lost world.

“We are time, we are history,” she tells Mark. “Remember us, gather us, read us, before we are dust.”

At YIVO, Mark’s legend and work continues, with staff members like Weiser and Kaplan making its millions of artifacts accessible. (Mark died in 1975, well before the internet and digitization proved essential tools for preserving historical memory.)

Mark’s daughter saw the opera in a concert version last year, as did many others who knew Mark and Weinreich. As Weiser and Kaplan float from their jobs at YIVO upstairs, down to the ground-floor auditorium at the Center for Jewish History, they see the opera as an extension of their work.

“If there’s any way this can illuminate the history for people, I think we’d both be very proud of that as a result,” said Kaplan. “And if it gets people more excited about Yiddish, about Yiddish history and culture, Jewish history and culture more broadly, all the more so.”

Weiser and Kaplan’s The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language has performances Sept. 18 and 21 at the Center for Jewish History in Manhattan. Tickets and more information can be found here.