These Forgotten Women Artists Shaped Vienna’s Modernist Movement

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

In 1938 when the Germans annexed Austria, the art world suffered a major blow.

Modernists like Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt had their work labeled degenerate. Jewish artists were forced to flee and many more were unable to. One more casualty of the Anschluss is often overlooked — the many women sculptors and painters whose names and works were lost to history. Until now.

A new exhibition, “City of Women” at Vienna’s Belvedere Museum, highlights the work of around 60 female artists, according to the BBC. Much of the work is being shown for the first time since the end of World War II.

“Pictures of these great women were sometimes stored in attics or hidden in repositories without anyone’s knowledge,” the exhibition’s curator, Sabine Fellner, said in a statement. “We have brought an important page of art history back ‘to light’ in the truest sense of the word.” Many of the artists managed to have their work showcased and celebrated in their lifetime, largely due to their own self-advocacy. In 1910 a group of women formed the Austrian Association of Women Artists (VBKÖ) during a time when women had to learn their craft from expensive private teachers. It was only a decade later that Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts admitted women.

But even before these developments, the Jewish artist Broncia Koller-Pinell, was making a name for herself both in Vienna and abroad.

Throughout the exhibition, her artwork, which covers eclectic movements such as Impressionism and Secessionism, connects the different schools emerging in Austria at the time the Belvedere noted in its press materials. Koller-Pinell died in 1934 and with the rise of the Nazis was largely forgotten while her contemporaries, Schiele and Klimt persisted in memory. Among the Koller-Pinell works on display is “The Harvest,” a 1908 painting that Klimt’s artist association, the Kuntschau group, debuted.

Another artist on view in the exhibition, which covers the decades between 1900 to 1938, is Friedl Dicker. Dicker, a left-wing artist who taught at the Weimar-Bauhaus, was subject to Nazi interrogations that informed her paintings. She painted two expressionistic scenes of interrogations, “Interrogation I” and “Interrogation II,” which are included in the exhibit. Dicker was deported to Theresienstadt, the “model camp” where she taught art courses to children, in 1942. She was murdered at Auschwitz.

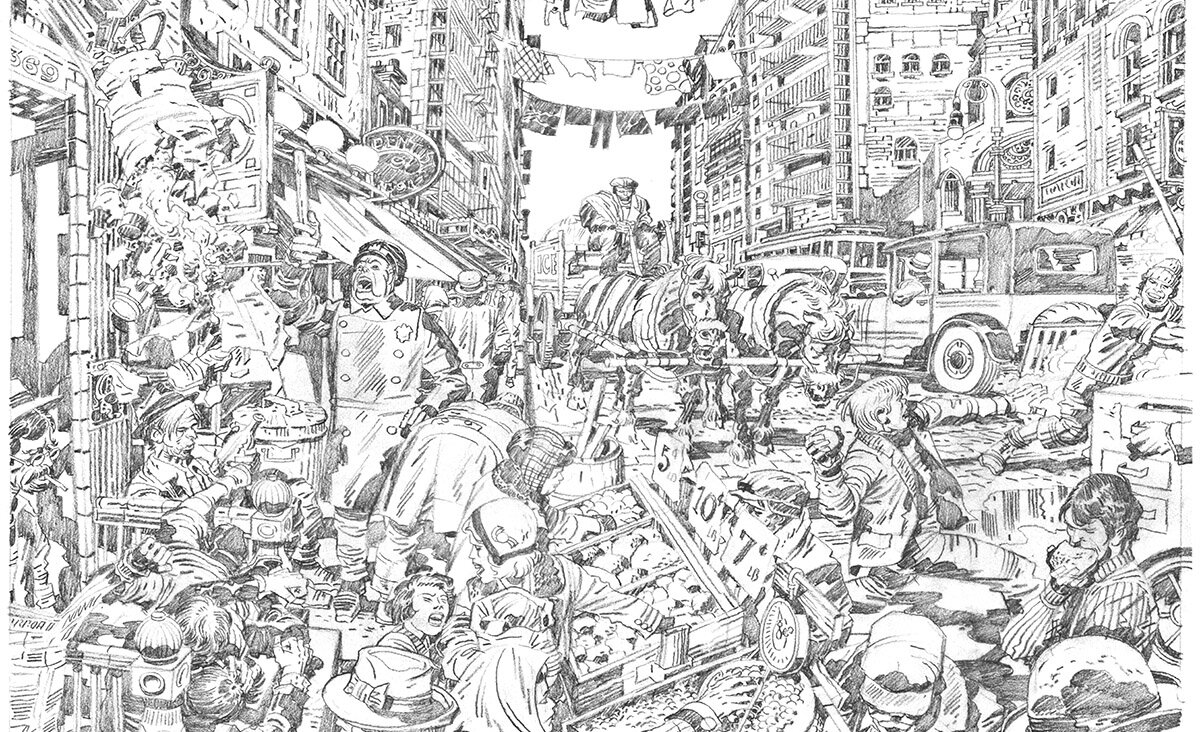

Ilse Twardowski-Conrat “Bust of Empress Elisabeth.” Image by © Belvedere/Vienna

The terror of the Nazi regime affected Ilse Twardowski-Conrat earlier than many Austrian artists as she worked extensively in Germany. In 1935 she had to surrender her sculpting studio in Munich. While her work is more classical than most of the “degenerate” artists in the exhibition, she was not allowed to practice her trade in Munich because of her Jewish heritage. In 1942 Twardowski-Conrat received her deportation orders, she then destroyed most of her larger pieces and took her own life.

Other influential figures in the exhibit include landscape painter Tina Blau, sculptor Teresa Ries, the Impressionist and Fauvist-inspired paintings of Helene Funke and a number of works by Elena Luksch-Makowsky. Luksch-Makowsky caused controversy in the art world with her 1902 painting “Ver Sacrum,” in which a woman in the working wear of painter’s overalls holds up a baby in a pose reminiscent of classical depictions Mary and the baby Jesus.

In a statement, the Belvedere’s artistic director, Stella Rollig emphasized the exhibition’s goal to “make the forgotten female side of this epoch visible in its full dimension. The artists of those years were and still are a great inspiration, and their works have been wrongly ignored for almost a century.”

PJ Grisar is the Forward’s culture intern. He can be reached at [email protected].