Why Queen Esther was the star in the age of Rembrandt’s Amsterdam

The figure from the Hebrew Bible was adopted as a figure of national self-determination in the Netherlands

Jan Steen’s The Wrath of Ahasuerus. Courtesy of Museum Bredius, The Hague, Netherlands

If you were to visit a home in Amsterdam in the 17th Century, you might find, in the kitchen, the library, or even inside the fireplace, a scene of the biblical Queen Esther approaching her husband the king.

In galleries, you could see the queen, who Jews commemorate every Purim for her salvation of the Jewish people in ancient Persia, in paintings by Rembrandt, his pupils and contemporaries.

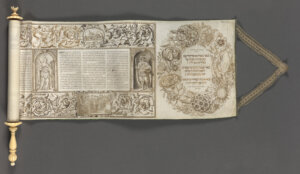

In the newly-built Portuguese Synagogue, or at the Schouwburg Theater, you could relive the story of Esther’s courage, as read from an illustrated scroll or performed live by actors, and if you needed a pick-me-up before Haman’s summary execution, even take a pinch from a mother-of-pearl snuff box with a lid depicting the tale’s climax.

“It’s almost like she’s just ever present in the 17th century Netherlands,” said Abigail Rapoport, the curator of Judaica at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan. Esther, whose name shares a root with the Hebrew word “hidden,” was everywhere.

In the new exhibition, The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt, Rapoport and her team have gathered 120 artworks, such as domestic items like firebacks and Delft tiles, dramatic tableaux from Dutch masters and ritual objects like ivory-handled Esther scrolls. The collection makes the case that for the newly free Dutch, who fought an 80 year war for independence from Spain, Esther was a star — and her name in Persian means as much — for her resilience in the face of persecution.

Esther’s Eastern milieu, exotic to Dutch artists and patrons then trading with the Safavid Empire, was an attractive subject ripe for Rembrandt’s innovations. But the heroine’s story also stood in for a real-world population of Jews in the republic, who came to the Netherlands to enjoy religious liberty after generations of living as conversos during the Inquisition.

“Esther was not unlike their own ancestors and families,” Rapoport said.

The exhibits gallery, which begins with a survey of Jewish history in Amsterdam, holds a collection of illustrated Esther scrolls by the Jewish artisan Salom Italia, alongside silver Purim cups demonstrating the prosperity of the community, which began arriving in the late 16th Century and resuming the open practice of their faith. (One scroll is in Spanish, indicating the language’s continued ritual use.)

But most striking are the works by gentile artists, whose embrace of Esther likely even factored into their portraits of royalty, three of which are on display. Rembrandt’s Esther portrait, given its own wallspace, stares straight at the viewer, her mouth in a slight smile, hand to her breast as she decides to risk death to save her people from Haman’s plot.

Taken together, the oils and etchings tell the whole story of the Megillah, with a shadowy painting of Mordecai overhearing the plot of Ahaseurus’ guards and scenes of his triumph on horseback.

One of the few paintings of Esther with Mordecai, by Aert de Geulder, is sensational for its use of light and detail — you can see the ink under Mordecai’s nails as he writes what may well be the plea for his kinsmen to fast and dress in ash and sackcloth while they await death or a last minute reprieve. Yet another portrait shows Esther in her raiment, holding wedding gloves, a popular prop in Dutch portraiture, collapsing biblical time and the contemporary moment, reshaping Esther as a modern Dutch woman.

The most common tableaux, which feature both familiar still life and orientalist ornament, are of Esther’s toilette and her feast. In both, Esther is the focus, bold and selfless, clutching a scroll bearing the words of Mordecai: “who knows, perhaps you have attained to royal position for just such a crisis” or pointing accusingly at Haman, revealing herself to be a Jew in the process.

At the feast, Haman cowers or pleads as the turbaned King Ahasuerus rises in anger, in one image sending a meal of peacock clattering onto the floor, shattering a blue and white ceramic vase. The poses are likely borrowed from theatrical productions popular at the time.

The exhibit, in the works for five years and joining together holdings from 35 museums and 10 private collections from all over the world, coincides with a rising interest in Esther in the United States. (The exhibit, made in collaboration with the North Carolina Museum of Art, will travel to Raleigh after its run in New York and then the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.)

While she is a figure of largely seasonal interest for Jews, recently the evangelical right has claimed her, and even likened her to President Donald Trump. On the other side of the aisle, Kamala Harris mentioned Megillah’s quote “for such a time as this” at a 2024 televised town hall during her campaign for president.

“What I find fascinating is the spectrum of voices who have employed Esther,” said Rapoport. “What’s amazing is that mirroring, of how today she’s bringing together people of diverse backgrounds, and at that time she’s bringing together Dutch Protestants and these Jewish immigrants. That’s a really powerful resonance without even trying.”

The Jewish Museum’s exhibition The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt opens March 7 and runs through August 10, 2025. Tickets and more information can be found here.