How Yiddish authors made a new world writing for children

Miriam Udel’s book tracks the development of literature made to shape a Jewish universe

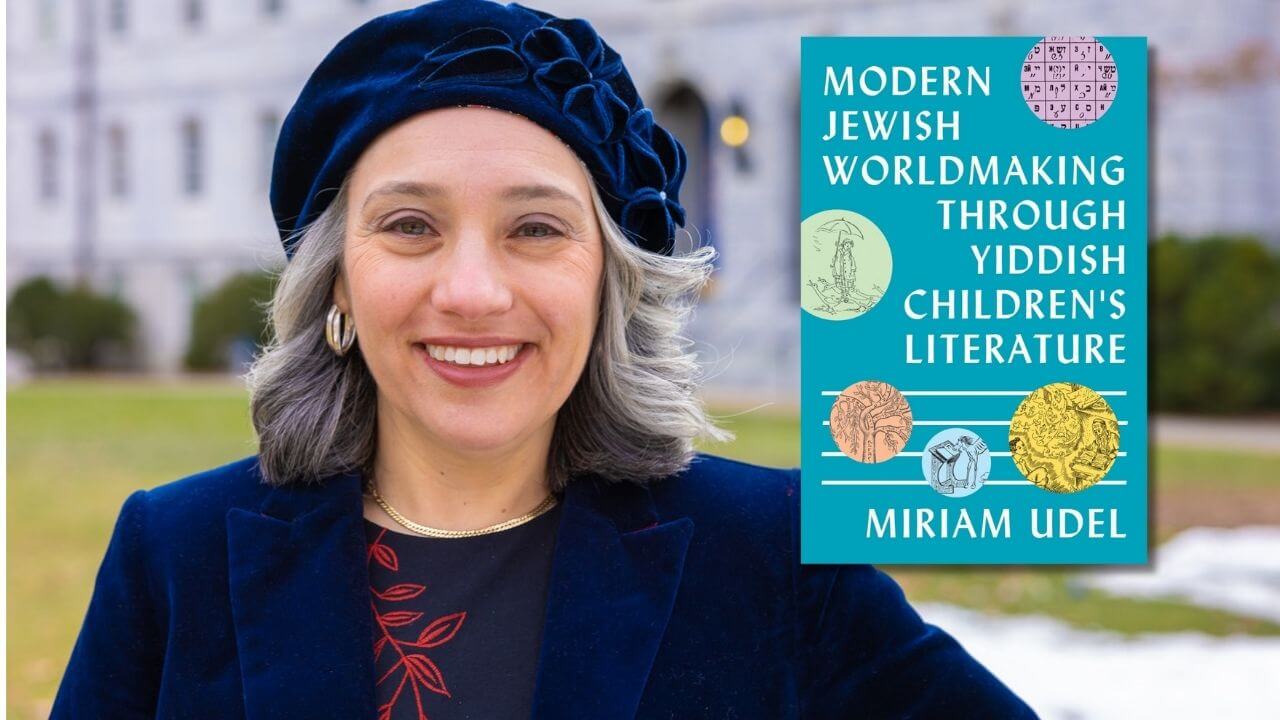

Miriam Udel’s new book traces the development of a Yiddish canon for young people. Courtesy of Princeton University Press

An intrepid puppy who marches for labor rights. A 6-year-old girl who sews herself a locomotive to carry her away from her daily chores. A Jewish boy who would be Pope.

These stories, written in Yiddish, are all entertaining and whimsical, and like so much writing for young people, may be seen as less than serious. But they were also composed as part of a larger communal project that was widely regarded as urgent. Beginning in the late 19th century, Jewish thinkers outlined the need for a children’s literature in the vernacular as a way to shape the future.

As Miriam Udel writes in her new book, Modern Jewish Worldmaking Through Yiddish Children’s Literature, these authors sought to “write a better world into being in a distinctively Yiddish key.”

Arriving at a time of competing nationalisms — communism and the socialism of the Jewish Labor Bund on one side, Zionism on the other — Yiddish writing for children began in Eastern Europe. It then spread to New York and, with the migration of Jews, Latin America.

Udel’s book is structured around the evolution of the canon, that, after the Holocaust, reexamined its purpose, pushing for literacy and what she calls the “rhythms of Jewish time.”

The writers responsible for Yiddish literature came from various political stripes. Some were educators and academics and others first made their names with stories for adults. Their work ranged from naturalist accounts of a Bund sanatorium to mythic tales of travelers on the Sabbath. Yet within nearly every story a theme of social justice rings through.

Udel, the compiler and translator of the Yiddish children’s story treasury Honey on the Page and the force behind a hit puppet show based on Chaver Paver’s stories of Labzik the communist puppy, researched nearly 1,000 works for the book.

“The overarching goal is to create literature that is going to make its readers want to joyfully and affirmatively choose Jewish identity,” Udel said of Yiddish children’s literature after the Holocaust. “This is an idea that I see us kind of rediscovering now.”

I spoke with Udel, an associate professor of Yiddish language, literature and culture at Emory University, about how this literature developed and changed to meet the times, and why Sholem Aleichem, for all his talent, had “no game” writing for kids. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I think a lot of people might be surprised that the first Yiddish children’s stories can be dated, and that it’s only really back to 1889. Why did it take so long to develop?

Children’s literature is very much a function of changing ideas about what childhood is and what children need. For a really long time, differences in age were much less important than differences in gender. Instead of boys and girls, we really had proto-men and proto-women. It’s really only when we’re starting to get these modern ideas about childhood as a protracted period, as a time for education and leisure [that this emerges]. We had an ideal of education for Jewish boys since time immemorial, but the idea that both boys and girls would have this time available that could be filled with the activity of reading, that was really new, and that was a product of economic changes, as much as cultural and educational developments,

It was also wrapped up in these nationalist movements that were emerging, the secular nationalist movement for Jews that produced the Yiddish school system. What were the cultural changes there and how did they lead to this literature?

By the turn of the 20th century, we have a pretty well-fleshed-out modern idea of what childhood is and what children are. Their job is to become educated, and there is a delay before we expect them to take up the burdens of adulthood, and at the same time, there are a lot of different nation-building projects underway. We can look to Mandatory Palestine as it prepares itself to become the State of Israel, and the way that Hebrew children’s literature is created out of whole cloth for helping to define who would be the citizens of this new Jewish state. We can also look to the Soviet Union. The revolution is going to remake humanity, and so it’s an efficient shortcut to start with the very young who could be imagined as a blank slate onto which you can write the story of your new state and your new citizenry. In the case of Yiddish, there are some of those cultural nationalist impulses, but it’s complicated because it bumps up against the reality that Yiddish really never comes close to being the language of a conventional nation state. And so instead of Yiddish being recruited into a conventional nation-building or state-building project, Yiddish gets recruited into what I call “worldmaking,” which is a project of creating symbolic polities and structures that children are going to be able to inhabit in, and through, their encounter with Yiddish.

The bulk of this genre is coming from mostly secular writers, but you note a lot of the stories seem to involve Shabbat and stories of the cheder. Why did these secular Jewish writers gravitate towards content that was in some way religious?

Everybody, no matter how secular they felt, had to deal with a question of, “What is the significance of the Jewish past?” “What is the significance of the language that has been handed down to us as a mother tongue?” And “How can this shared, collective past in some way shape the future?” Some of them don’t deal with the past — everything is very forward-looking, and that’s where we actually tend to see a lot of girl protagonists. The future is female for Yiddish children’s literature. Whereas we see our cheder stories, our school tales with boy protagonists that orient themselves toward the past, and sometimes we see authors digging into a very deep, rich kind of Jewish past in order to pull up something that they think will be of use now and tomorrow.

That’s what happens with a subgenre that I write about the Sabbatarian tale, that describes somebody observing a very traditional, even Halachically-informed Sabbath under vulnerable circumstances, where maybe it wouldn’t even make sense for them to choose the immobility and all of the ways that the Sabbath grounds you in a negative sense, they are nevertheless choosing to uphold the Sabbath and finding that it grounds them in a positive sense. There’s a convergence point between the very traditional idea of a regular cessation of labor every seven days and the most cutting-edge socialist thinking about the worker being able to reclaim time from the boss and say, “1/7 of my time doesn’t belong to you.”

There are some sort of bold-faced names showing up and trying their hand at this literature. We have Sholem Aleichem trying his best. What do you make of the writers that are maybe more familiar to us and their efforts, and who are some writers that we might not know about who stand out?

Across Jewish literatures, several decades into the 20th century, there’s a sense of almost civic duty to try your hand at writing something for children, and some of them are terrible. One of my favorite Yiddish authors for adults, Yisroel Rabon, writes this super weird novella that I wrote about at length in my first book, Never Better! It’s violent and disturbing and terrible, and I would never put it before children in my life. And then we get someone like Sholem Aleichem, who wrote so brilliantly about childhood and child characters from the perspective of adulthood, but really had no game when it came to addressing living, breathing children. And he was such a bold name that they tried to retrofit his stories to appeal to children. It became canonical because he’s Sholem Aleichem. And then you get someone like Isaac Basevis Singer, who’s really already made quite a name for himself as a novelist and a writer for adults. And [Elizabeth Shub], the daughter of a legendary children’s editor of the Kinder-zhurnal, who becomes an English language children’s book editor as her career, goes and recruits Isaac Bashevis Singer to write for children.

And he didn’t know how to do it. He had to really kind of stumble his way into some kind of address to children. So he started out trying to write rhyming poetry, because he thought that’s how you talk to children, literarily, and it was stilted and it was terrible. And she told him, “Itsik, go back to the drawing board.” He kind of cracked the code and figured out his formula, and he started producing these really heartwarming tales of the old country, and he was able to pour a sense of hopefulness and decency that he only half believed in for adults into these children’s stories.

Then as this enterprise of writing for children in Yiddish and publishing arms gets going, it becomes professionalized, and it becomes the province of both professional educators and also people whose whole career is write for children, or who wrote somewhat for adults, but also somewhat for children. And then we start to get figures like Zina Rabinowitz, who’s one of my favorites. Last year I did this project, 5785 where I published a new Yiddish children’s holiday tale before each one of the holidays that ran in the Forward. And one of my go-to authors was Zina Rabinowitz. She’s writing in the 1950s, but she really understood how to address kids, and it was a very smooth process to translate her, and her psychological intuitions about children and childhood were very much in keeping with our own.

A large part of it for the Americas was how to communicate about the Holocaust. Part of the approach was stories of resistance or metaphors — the life of a tear shed by a boy who was deported. Can you talk about how they tackled that?

One of the really important figures in thinking about this and kind of theorizing what to do was Yudel Mark. He’s publishing articles in 1941 and 1943 and 1947 reflecting on what they did and how they did. And he says “We may have sinned against child psychology.” So there’s an awareness that there is a field devoted to children’s wellbeing, and that field has made everyone aware of children’s vulnerability, and that it was worth overriding that concern in order to let Yiddish-speaking Jewish children know what was happening to their cousins and how to go on and live their own Jewish lives in light and in spite of what had happened to European Jewish children.

Something that comes up as a theme — there’s tzedekah for a poor person on Purim, even in the first story — is building empathy for readers.

The single most frequently occurring theme across all the varieties of Yiddish children’s literature, is the persistence of wealth inequality and the need to redress it in some way. The prescriptions for what to do or what to focus on in redressing wealth inequality really vary, particularly by political stripe. This is where we can sort of dig down and see where an author situated themselves on the ideological spectrum. And so we have Kadia Molodosky writing a beautiful story “The Beggar and the Baker,” about the traditional value of giving tzedakah, of charitable giving as a matter of justice and as a matter of pre-paying a debt that you don’t even know exists yet, because that’s what the baker does. He gives challah every week to all the beggars, including one with radiant eyes. And when the bakery burns down and the baker is left destitute, along comes the beggar of all of those years whose fortune has changed, and he’s come precisely to pay back and discharge the debt.

And we have other stories that speak in the language of tzedakah. We have a story of a little boy’s political awakening, realizing that as a kind of well-off, middle-class kid with everything that he needs, there’s a whole economy and political order that’s been created to make sure that he has down feathers in his pillow and wool to be sewn into the suit that he wears, and leather for the shoes that he wears, and that other creatures have suffered and died, and that other human beings are working at hard jobs, like the washer woman, so that he can have nice things. So there’s his coming into political awareness.

And then, going further out on the left, we get a story about the birds of the forest who organized politically to liberate the urban birds who are dwelling in cages. And the story really walks its child reader through the mechanics of labor organization and collective action. And so everyone wants to fix wealth inequality, but people have really different ideas about how to do it and what to emphasize.

The state of this literature now is mainly from the Hasidic world. Do they read any of these, these old secular writers and their Shabbat stories? I know the orthography is different.

It’s not like there’s a kosher version of Kadia Molodowsky or Isaac Bashevis Singer. There is, instead, just alternate content that originates in that community. There might be Yiddish children’s versions of midrashic stories, stories from rabbinic literature, that got an update in the 1910s or the 1920s and those same stories have formed the basis of materials for contemporary Hasidic children. But that would be sort of incidental. One thing that I did see, and actually my favorite of the contemporary Hasidic children’s books that I own, is a graphic novelization of a Rebbe Nakhman story about a wise man and a fool, and the production values are really high. The illustrations are great, and who doesn’t love a graphic novel?

What does the future of the genre look like for non-Hasidic Yiddish readers, a growing cohort having kids now.

One of the ways that I got into this research area is that I was looking for children’s materials that originated in Yiddish, not necessarily something that’s been translated into Yiddish or translated for pedagogical purposes, that would be simple enough that my students could productively read it in the second semester. And I thought, “Is there any children’s literature?” And so now I get emails all the time from people who are using Honey on the Page to locate children’s literature, which they are then using to further their Yiddish education. I think that some of these stories really want to exist in new forms, and as picture books and as graphic novels. I actually just got the go ahead from the peer reviewer on my translation of Labzik, which SUNY is going to publish in August. All 12 Labzik stories. And I think Labzik is desperately eager to become a graphic novel. And I think Labzik wants to be animated. The puppet film was so successful. I think there’s a lot more where that came from.

I do think that it’s a time of renaissance, and that children’s literature is such an exciting frontier, because it’s a way to build interest from and grant access from a very young age. It’s something that multiple generations can share with each other with great pleasure and profit. And then, for the people who do make the leap into studying Yiddish, whether it’s through Duolingo or a class, it gives them a way to progress with their language study, so it can do all of these different things for us that feel like they have a lot of currency right now.